INTRODUCTION

Worldwide shortages of the registered nurse (RN) workforce have increased the recruitment by wealthier countries of internationally qualified nurses to meet healthcare demand (Catton, 2020). The International Council of Nurses (ICN) report, “Recover to Rebuild” (Buchan & Catton, 2023), suggests that this critical workforce deficit stems from a confluence of factors. These factors include, though are not limited to, rising rates of burnout among nurses exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic; inadequate staffing levels leading to overwhelming workloads; consequent lack of retention of the workforce; together with insufficient support for mental health and wellbeing (Buchan & Catton, 2023). Furthermore, the report underscores that these issues are compounded by an increasing aging population, increased demands for healthcare services, ongoing inequalities in healthcare access disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations, and increases in health disabilities (Buchan & Catton, 2023; World Health Organization, 2021). Therefore, many countries face significant challenges in meeting the resulting health and social system demands for providing long-term complex care across the lifespan.

International nurse migration is now a well-established phenomenon for nurses responding to the increasing demand for workforce recruitment (Buchan & Catton, 2020; Cubelo et al., 2024; Winkelmann-Gleed et al., 2022). Factors affecting the moves of professionals from the country of origin to a host country are conceptualised as ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors (Kline, 2003). These factors indicate the wish to experience better working conditions, remuneration, professional development, career advancements, and better life and education opportunities for families (Khalid & Urbański, 2021). The prospect of improved living and employment environments is a critical pull factor for many professionals looking to emigrate (Kowalewska & Markowski, 2024). This prospect is further fueled by opportunities to assist their families financially by sending remittances home and improving their knowledge educationally or using migration to bring the family with them to the host country (Villamin et al., 2023). The ICN suggest that coordinated efforts to provide improved working conditions, and enhanced education and training would create supportive environments to attract new nurses to the profession and retain existing nurses in the workforce (International Council of Nurses, 2023).

Aotearoa New Zealand’s recruitment of IQNs began to accelerate in 2010 (Clendon, 2012) due to the rising demand on healthcare (Nursing Council of New Zealand [NCNZ],2013; Ministry of Social Development, 2011; Ministry of Health New Zealand [MoH], 2016) and a lack of RNs available for employment to fill nursing vacancies. The percentage of IQNs in the workforce has increased in the past few years from 27% in 2020 to 44.7% at the end of June 2024 (NCNZ, 2024). As a result, Aotearoa New Zealand now has the largest quota of IQNs, as measured by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2021).

Prior to 2023, attendance on a competency assessment programme (CAP) was a mandated pathway for nurses migrating from countries where differences in professional hierarchy in the workforce and differences in the academic degree structures were seen as not equivalent to requirements for registration as a RN in Aotearoa New Zealand (NCNZ, 2015). The CAP provided a means of assessing nursing knowledge and assessing clinical and critical thinking skills to ensure IQNs met the required NCNZ nursing competencies. The CAP curricula was mandated to provide knowledge of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, Aotearoa New Zealand’s founding document (MoH, 2020), cultural safety in healthcare provision, the relevant legislation for practicing nurses, and an update of clinical skills (NCNZ, 2008). The programme took approximately eight-weeks to complete with the inclusion of up to six weeks of clinical placement.

Changes in the registration pathway for IQNs were initiated in December 2023, following consultation with key stakeholders (NCNZ, 2022) and supported by the doctoral research of the author’s study (Clubb, 2022) reported here. While competence assessment for IQNs has changed considerably since 2023, it is important to capture the knowledge gained from the experiences of IQNs pre-2023 and describe the learning and support needed to transition into the Aotearoa New Zealand health system. This study adds to the body of knowledge both nationally and globally and is likely to inform future evaluation of the transition of IQNs.

Aim and research questions

This study sought to understand how IQNs perceived the relevance and usefulness of the competence assessment programme to their clinical and cultural integration into the Aotearoa New Zealand nursing profession.

The research questions were:

-

How useful was the clinical placement experience of the CAP in comparison to their previous nursing experiences overseas?

-

How did the concept of cultural safety content support an understanding of Te Tiriti o Waitangi and its implementation in healthcare in Aotearoa New Zealand?

-

What elements of the CAP experience were seen as relevant to their integration into the nursing workforce?

-

What implications could be drawn from these answers to inform future IQN nursing registration processes in Aotearoa New Zealand?

METHODS

Design

A qualitative approach using focused ethnography was chosen for the study. This approach utilises the ability of the researcher to study and interpret the social world, or culture, of the participants to understand their beliefs, behaviours, and experiences in both a cultural and societal context (Cruz & Higginbottom, 2013; Higginbottom et al., 2013; Roper & Shapira, 2000). This study examined a sub-culture of IQNs presenting their responses on how the CAP assisted them with their transition into practice as RNs in Aotearoa New Zealand. Furthermore, it provided a direct emphasis on how their cultural backgrounds and previous nursing experiences gave them meaning and understanding of general nursing practice in a different country and supported the use of their own words and interpretations of experiences to provide the data for interpretation (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Focused ethnography can include observing the researched people, environment, or situation, however, in this study, the research aims and questions around participants’ perceptions of a past event, the CAP, prohibited options to observe participants in the field. Nevertheless, journal notes were made immediately following each acceptance of the invitation to participate and detailed the participants’ demeanour during the interview.

Ethics

Ethics was approved by Auckland University of Technology Research and Ethics Committee (18/328/17 Sept 2018). Participants were anonymised following privacy and confidentiality policies, and written informed consent was obtained. Compensation for participation was offered by way of a monetised gift card.

Settings, sample, and data collection

The study took place in the upper North Island of New Zealand with participants who were working as RNs in aged care facilities or local public hospitals. A choice of setting was provided to support a comfortable and neutral area. Purposive sampling with cultural grouping (Parahoo, 2014) was used to recruit IQNs from the Philippines and India, as these were the most common countries of origin for CAP programmes nationwide at the time (NCNZ, 2022). Additionally, criteria around the need to have two years post registration in Aotearoa New Zealand was added to ensure adequate time for them to have transitioned into their RN role and be able to reflect on and determine relevant experiences to respond to the research questions. Initially, the choice of attendance at focus groups or individual interviews was offered to the participants, however, preferences for face-to-face interviews were implemented due to the early feedback that the cultural values and hierarchies from Philippine and Indian culture might inhibit the contribution to discussions in group settings.

Semi-structured interviews were undertaken for recording data collection using an open-ended question guide to obtain important information in responses and a larger amount of material for analysis (Geertz, 2017). This practice maintained the premise of the focused ethnography methodology as it supported the cultural aspect of the study and encouraged the participants to expand on their responses concerning their subject of discussion in comfort. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed, then verified against the saved audio recordings before being thematically analysed. A questionnaire of demographics was completed by each participant before the interview commenced. Journal notes were made immediately following each acceptance of the invitation to participate and after each interview.

Data analysis

Analysis of the transcribed interview data, field notes and demographic data occurred using Braun and Clarke’s (2021) thematic analysis coding process. Initial familiarisation of the data began with the repeated immersive reading of the transcribed documents, combined with replayed interview recordings to supplement the related observational field notes noting pauses and exclamation points not represented in the written words (De Chesnay, 2015). Next, close examination of the text sheet led to reflexive pattern consideration and searching for meaningful words and phrases, followed by a generation of codes for these. These codes were then sorted into sub-themes, becoming overarching themes, after re-interpretation of the data groupings and cross-referencing between the initial codes and sub-themes (Lainson et al., 2019). The credibility of the analysis findings was carried out with the use of non-verbal observations and a constant review of the transcribed data to allow initial and subsequent interpretation by the first author, an RN completing a doctoral programme at the time of the study. Finally, the discussion between the researcher, and the supervisors of the doctoral candidate, supported reflexive triangulation of the data sources and emerging themes identified (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

FINDINGS

The demographic data of participants is shown in Table 1. Over the nine months of recruitment and data gathering, twelve participants responded to the invitation (n=12), eight from the Philippines (n=8) of whom six were female and two were male, and four from India (n=4) of whom two were female and two males. Six worked in aged care settings and six in hospital settings. Participants were aged between 26 and 50 years and had worked as an RN in Aotearoa New Zealand for between 2 to 20 years.

Social interaction: Communication barriers and the need for helpful preceptors and mentors

Theme one relates to the experience’s participants shared related to their ability to understand the colloquial accent and different nursing terminology used in their CAP professional practice components. All the participants had English as a second or third language and the getting to know the ‘Kiwi’ accent was reported to be challenging in respect of the usage of foreign words, slang, and pronunciation:

I didn’t know the Kiwi accent was so strong, so the CAP helped me get used to it because back home the accent was mainly more on the American side. For example, some patients will be asking “Can you lower the ‘hid’ of the 'bid”. So, I was like ‘Oh, the head of the bed!’. (Joy, 5th-year NZRN, Filipina)

The Philippines is so American so there are a lot of things like what we call instruments, including textbooks. In NZ it’s done differently, or we call the equipment different. In terms of practice, none of them violates any principles or sterility or anything. (Joseph 7th year NZRN, Filipino)

Preceptors were held in high regard and their support, communication processes and guidance throughout the course were seen to have had the most positive effect during the participants’ transition to Aotearoa New Zealand nursing practice:

My preceptor was really good, I was lucky that she was structured and experienced. It was a critical thing for me and it’s good to have a good example to follow. (Py, 5th year, Filipino)

I think it really counts because that is somebody leading you on, taking you through the road so that you know you won’t get left behind. (Aiko, 3rd-year, Filipina)

Navigating new professional practice: Feeling deskilled in unfamiliar roles, and misconceptions around cultural safety and Te Tiriti o Waitangi

The second theme related to the transition to a new way of practising as an RN in a new country. Several sub-themes in adapting to a new professional practice were revealed outlining how the clinical placement settings and new RN role expectations were confusing for the IQNs.

The clinical placement provisions differed in each CAP provider’s locality, with most occurring in aged care facilities, an unfamiliar clinical area to IQNs, highlighted in their reports of no similar institutions existing in their home countries:

I didn’t have a choice other than going to aged care facility really. (Anu, 6th-year NZRN, Indian female)

In the Philippines, we usually take care of our own elderlies at home. Or hire nurses 24/7 to come in the house. (Michaela, 3rd-year NZRN, Filipina)

Experiencing unfamiliar practice areas to that of their home countries, such as aged care and mental health, posed considerable difficulties for IQNs, reported as “having been deskilled”. Specific reports of how the CAP practical skills undertaken in the clinical component were only “50%” like practical skills undertaken in their home country were noted. Many participants spoke of “going back to basics” and that the course content was “basically the same” as their prior nursing education content. Participants expressed frustration around their lack of learning something new, in turn described as undertaking “non-complex” nursing interventions, and consequently saw this was not meeting their expectations:

I was expecting something big to learn, but what we learnt is something that is basic, that we already knew before. We already trained for four years and then come here and just give the medicines like, I’m doing nothing. (Sijoy, 6th-year, NZRN, Indian male)

Additionally, participants expressed disappointment in not having their previous nursing experience acknowledged. Many participants recounted the number of years they had taken to obtain their nursing degree in their own country, and some felt that the CAP was both ‘humbling’ and ‘expensive’ and that their clinical placements were only observational exercises:

So, when it comes to being here, after doing four years, three months of competency is nothing for us. I still remember all they asked me to do was to check the vitals. Why are we paying to do a two-month or six-week course when we already learnt that spending the same amount in India for four years? (Joseph, 7th-year NZRN, Indian male).

Some participants were frustrated with the inability to carry out clinical tasks or skills they had gained in their initial nurse education. All participants referred to themselves as “students” whilst on the CAP and gave examples of working under supervision, following the lead of the RN, or following the tasks laid down for the course completion. They felt deskilled due to their inability to use their prior nursing skills from their own country in their designated placements in aged care:

We can only do certain things like, as I said, IVs we can’t do. So many things we can’t do, we need to take them [patients] to the hospital (Deena, 7th-year NZRN, Indian female)

However, a small number of participants who had clinical practice placements in acute hospital settings spoke about engaging with new protocols for nursing care provision that used different professional language and could be practiced in Aotearoa New Zealand:

I think in general like assessments or doing care plans, they’re almost the same. Apart from parameters [vital signs]. But during my experience as a CAP student, we have guided outlines to be done and now as an RN, we do independent nursing actions. (Lucy, 5th-year NZRN, Filipina)

The IQNs attested that there had been minimal CAP content on accountability to practice and decision-making, and that such learnings had taken place subsequently in their practice roles:

On the CAP, I hardly made any decisions because we had an RN with us. (Sijoy, 6th-year NZRN, Indian male)

Participants, commonly expressed surprise in the symmetrical power balance between health professions within Aotearoa New Zealand workplaces when compared to those in their home countries:

It’s much different. So, here the RN gets a big importance. You have a voice here, you can decide on things, you can actually correct doctors, that voice that you have is big. We don’t have that in India. There, they tell us what to do and we do what they tell us. (Anu, 6th-year, NZRN, Indian female)

For example, doctors in their home countries were seen to not be questioned, were revered, and “almost worshipped”. Some participants reported that it had been uncomfortable to call the doctors by their first names during the CAP and that this discomfort extended to tending to call their CAP tutor and their preceptors by the salutation of ‘Miss’ rather than use their first names. Several participants explained that witnessing the collegial behaviour of their preceptors was helpful with their own interactions with doctors:

I could see that my preceptor was questioning the doctor. It was helpful for me because I didn’t realise you can call them by their first name. It was a big thing for me because [in the Philippines] that’s a big no. We don’t do that. You respect them and you worship them. (Py, 5th-year NZRN, Filipino).

A Filipina participant suggested that from her perspective there was also a cultural variance how different IQNs accommodated the power shift:

There is a big difference between Filipino and Indian nurses. I find Indian nurses really stick to the letter of everything. Authority down the line, strict hard working, close to old school nursing, hierarchy kind of thing, where doctors dictate exactly what the nurses would do, and nurses dictate what the caregivers would do. Filipinos are a bit more on the casual side. Once they get friendly with their seniors, and doctors, and with staff below them as well, they’ll be OK. (Aiko, 3rd-year NZRN, Filipina).

All participants acknowledged that the professional culture in Aotearoa New Zealand differed from that of their home country. However, a male Indian participant considered that it was his responsibility to get to know the occupational culture of where he was working to ensure responsibility for his nursing actions:

We are always responsible back home for our registration, and we are accountable for what we do. And my understanding was I had to take responsibility for coming to a new culture. To know the culture better and respect [them] in terms of their values and everything. (Jacob, 10th-year NZRN, Indian male).

Culturally safe patient care provision was not regarded as a new concept by most of the participants. The inclusion of cultural safety in nursing in the CAP course was generally seen as unnecessary as participants felt they understood the concept well from their prior studies and work experiences. Furthermore, many participants felt the CAP clinical placement and length of time were not conducive to gaining cultural insight into their patients’ values and beliefs, in particular Māori or Pacific peoples:

Personally, I think cultural safety is within the person. It’s respecting the cultures that you don’t know and being aware of things that you are not aware of. (Joseph 7th year NZRN, Filipino).

CAP is very structured; it is not real life. In terms of the lectures and introducing culture on a big textbook base, I think that was good, but I think experiencing it in real life is always better. It’s six weeks of placement and it just depends on who you’ll get to interact with for those six weeks so it’s not enough to be honest with you. And to be fair, even if it’s a year, if you’re put in a job placement where you don’t experience something, you’ll never experience it. (Joseph 7th year NZRN, Filipino).

However, one participant expressed that she had changed her clinical communication behaviour due to her CAP experience and that it had accelerated her subsequent acculturation into the Aotearoa New Zealand workforce.

It was a bit hard, and you must be considerate. You must check yourself all the time. When I did my clinical practicum, I had various ranges of people. We must be really good in communication, not only verbally, so that we will be able to carry out our duties to our residents. For me it was a different shift in the kind of job that I have, aside from just giving medications, you also need to consider something else deeper than that. You must be considerate with the culture. Always think of the rights of the resident, always think of their safety. They should always be culturally safe, so if you keep your residents culturally safe and their wishes being followed, I think that’s the best thing that you can do. (Michaela 3rd year NZRN, Filipina).

Many participants appeared to have conflated their cultural safety sessions from the CAP with their sessions on health provisions under Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Examples provided were around how these IQNs had specifically followed the cultural beliefs and wishes of their Māori patients (tikanga) rather than how they should work with all Māori to achieve health goals. Several participants reported that their CAP sessions on Te Tiriti had been brief, and the content was unable to be recalled. However, there was a general understanding of the need to work toward advancing Te Tiriti with several participants who stated they had learned most of this knowledge after completing the course.

At that time of the CAP, we were not actually aware or familiar with the Māori culture and all that and the Treaty of Waitangi and the three Ps [principles for healthcare provision]. But when we had that half day, or three hours we were given the history and how were going to deal with Māori and what happened in the past and how we can deal with that in our nursing thing. After CAP I learned a lot when I started working when we had lots of Māori patients. (Maria 17th year NZRN, Filipina)

DISCUSSION

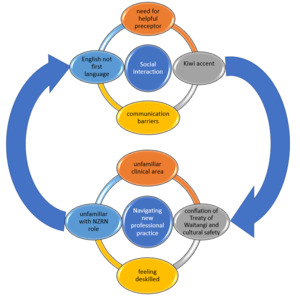

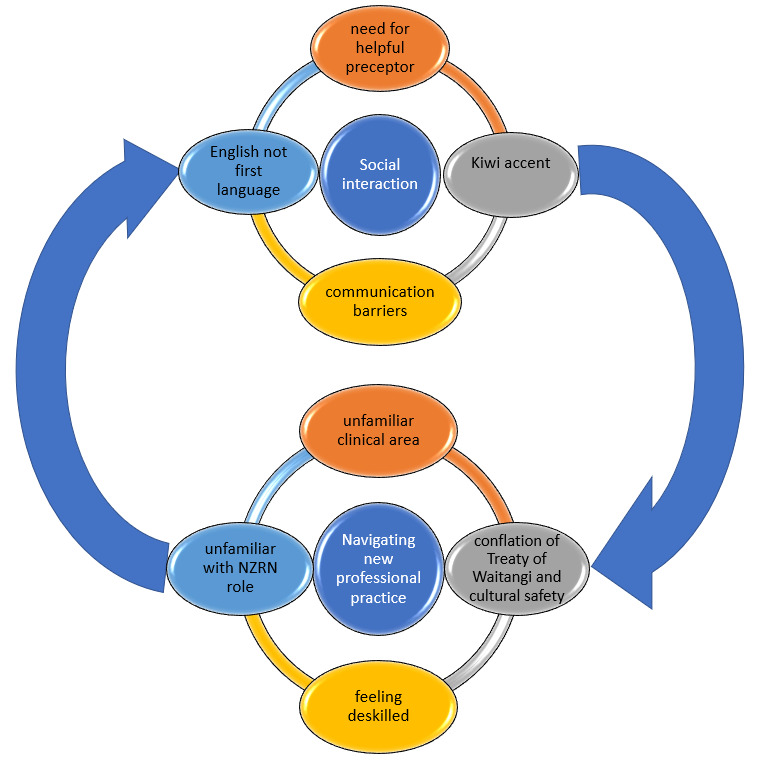

The aims of this study were to understand how IQNs perceived the relevance and usefulness of the competence assessment programme to their clinical and cultural integration into the Aotearoa New Zealand nursing profession. The findings were heavily influenced by a sense of social dissonance arising from the participants’ confusion and unfamiliarity with the social and professional settings in Aotearoa New Zealand as depicted in Figure 1.

A significant concern was their communication experiences, despite meeting the English language requirements for the CAP. Hui et al. (2015) reinforce that effective communication is a vital element in acculturation into a host country. Challenges related to accents and pronunciation align with the literature on the acculturation of IQNs into host countries (Goh & Lopez, 2016; Valdez et al., 2021). Notably, this study found that hands-on interaction with patients after CAP completion had a more positive impact on therapeutic relationships and aiding community integration than the course content itself.

Likewise, the use of unfamiliar nursing terminology, local jargon, and the absence of professional titles during the CAP clinical placement sparked confusion and frustration among participants. This could be due to the hierarchical nature of nursing professions in their home countries, namely the Philippines and India (Gill, 2018; Liou et al., 2013). This difference may have heightened language challenges leading to reduced confidence and feelings of being deskilled. Previous studies also highlighted communication barriers as a prevalent issue for IQNs in Aotearoa New Zealand (Bland et al., 2011; Brunton et al., 2020; Montayre et al., 2018) despite similar English language requirements to other developed countries. Notably, the support of preceptors during the CAP was found to be key in facilitating participants’ positive acculturation to social and professional communication.

The findings also demonstrated widespread confusion and dissatisfaction among participants due to their allocation to unfamiliar clinical areas, such as aged care, along with different nursing practices, protocols and professional hierarchies. There was also a perceived lack of recognition for their previous experiences, a concern echoed in the literature (Choi et al., 2019; Nourpanah, 2019; Steviano et al., 2017). This lack of recognition could lead to discrimination and create potential professional conflict. Post-CAP, participants acknowledged an evolution in their nursing skills and knowledge, with many feeling the course only provided a brief introduction to the nursing profession in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Participants also reported a shift in their understanding of the power balance between RNs and doctors. This finding aligns with global literature on the acculturation of migrant nurses (Choi et al., 2019; Goh et al., 2015; Nortvedt et al., 2020). Similarly, studies undertaken in Aotearoa New Zealand describe a progressive process of IQNs becoming aware of accepting the more egalitarian power balance between medical and nursing staff than that of their country of origin’s professional workforce (Brunton & Cook, 2018). This study’s findings identified the need to review the CAP course objectives concerning cultural adjustment and power balance shifts to ensure safety and competency in the workforce.

The acquisition of new knowledge on cultural safety suggests that this knowledge had been conflated with participants’ understanding of the implementation of Te Tiriti o Waitangi principles for health care provision for clients in Aotearoa New Zealand. The findings identified that CAP sessions provided on Te Tiriti had been brief and insufficient in their content to provide a deep understanding of the principles of patient-centred care and instead reflected awareness of the need to follow Māori cultural practices (tikanga). These results are consistent with the literature on the lack of confidence nurses have in Te Tiriti principles in healthcare provision (Richardson, 2012; Richardson & MacGibbon, 2010). Additionally, the low population of Māori and Pacific residents in aged residential care facilities in Aotearoa New Zealand (Keelan, 2024) would have had an impact on the opportunities to learn and practice both cultural safety and working towards Te Tiriti in a learning environment.

Finally, as discussed by Stievano et al. (2017) support from the host country is pivotal in enhancing migrant nurse integration into the host country’s workforce. While participants felt restrained in practicing their skills, they greatly appreciated the support from their preceptors during the CAP course. The preceptor experience was identified as the most significant component of the CAP course for most participants, in line with global research on the pivotal role of preceptors in facilitating the transition to new nursing roles for migrant nurses (O’Callaghan et al., 2018; Ramji & Etowa, 2018; Roth et al., 2021), as well as Aotearoa New Zealand-based studies (Brunton et al., 2020; Hogan, 2013; Walker & Clendon, 2012; Walter, 2017).

Limitations

Limitations of this study are recognised and include the following. Firstly, the sample size and limited regional recruitment site may not accurately represent the broader perspectives of Filipino and Indian IQNs in Aotearoa New Zealand. Secondly, due to professional hierarchical structures prevalent in the nursing workforce of the Philippines and India, participants may have perceived the researcher as a higher authority figure. This could have created a bias and possibly influenced their willingness to fully engage in the research process. Thirdly, the participants nursing experience in Aotearoa New Zealand ranged from two to twenty years. The latter time span may have impaired recall of the CAP course. Finally, there is acknowledgement that the expectations of use of Te Tiriti in healthcare provisions and practice as well as the expectations of preceptors in nursing have significantly changed in the subsequent twenty years.

CONCLUSION

The process of professional acculturation of IQNs into a host country’s nursing workforce is vital to maximising equitable population health outcomes. This study focused on examining prior students’ views on how the CAP course enabled their transition to safe clinical and cultural practice in Aotearoa New Zealand. The findings highlight that the CAP clinical and cultural component elements were not seen by the cohort to have sufficiently supported their transition into the nursing workforce. However, preceptorship provided during the CAP was highly valued, as was the redress of professional power symmetries being seen as the most enabling aspects of the CAP.

The study presented here informed a multi-stakeholder review of the CAP course curriculum in Aotearoa New Zealand, that was accepted and undertaken in 2022 by the NCNZ. The result was an announcement of the implementation of a new competence assessment and registration pathway for IQNs that commenced in early 2024. There are two pathways for IQNs to attain RN status: 1) Through to the end of June 2025, IQNs may undertake a CAP; 2) Undertaking a new competence assessment, comprising an online theoretical exam to test nursing knowledge (which is available overseas) and a two-day orientation and preparation course in Aotearoa New Zealand followed by an Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE), a clinical examination lasting three hours testing professional and clinical skills (NCNZ, 2023). Building on the knowledge of this study, together with experiences of IQNs from previous research will be essential to ensure IQNs are well supported to integrate in the Aotearoa New Zealand health system where they are valued and enabled to deliver safe and equitable nursing care.

Funding

None

Conflict of interest

None