INTRODUCTION

Aotearoa New Zealand has a large migrant Asian population with 34% of Asian people coming from India; 65% of whom live and work in Auckland (Eaqub, 2020). Despite the substantial number of Indian people in this group, information about their health and utilisation of health services is limited (Chiang et al., 2021; Singh et al., 2022). Singh et al. (2022) explored the experiences of Indian people living with a stroke in Aotearoa, finding four themes of importance to them, which included self-care, family support, social connections, and ethnicity not being a barrier to care. Indian people are the largest group of service users at the hospital where this research is situated.

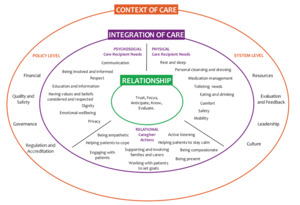

The hospital conducts a bi-annual peer review of care delivery which uses nine care standards to measure care (Aspinall et al., 2023). The nine standards were developed and adapted using an inductive approach to refining the fundamentals of care (as identified in the Fundamentals of Care (FoC) Framework), then applying them to the local context (Parr et al., 2018). Further detail about the development of the standards, adaptation, and methods used in the review have been described in the literature (Aspinall et al., 2023; Parr et al., 2018). Asian patients, of which Indian people form the largest subset, highlighted four areas for improvement in the results of this measurement and evaluation peer-review programme. The elements they expressed dissatisfaction with were communication, respect, personal care, and self-care (J. Parr, personal communication, March 2019). Each of these four elements are reflected in the Fundamentals of Care Framework (the FoC Framework) which is a point of care theoretical framework consisting of the context of care, the integration of care, and the relational activities at the centre of caring (Kitson, 2018).

The Framework illustrates the integrated care that nurses should provide to patients, family members, and carers (Kitson, 2018) (Figure 1). Feo et al. (2018) define fundamental care as “involving actions from the nurse that respect and focus on a person’s essential needs ensuring their physical and psychosocial wellbeing. These needs are met by developing a positive and trusting relationship with the person being cared for as well as their family/carers” (p. 2255). The four areas for improvement that were identified in the peer review and focus of our study, sit within the integration of care sphere. Communication and respect can be found in the psychosocial domain, personal care in the physical domain, and supporting self-care is encompassed in relational care giver actions, whereby nurses support patients to achieve their goals, support their ability to cope, and involvement in their care.

The peer review improvement programme identified that Māori, Pacific, and Asian patients were dissatisfied with some elements of the care they had received. Consequently, three studies were designed to explore the issues faced by each of these patient groups receiving nursing care in a tertiary hospital in Aotearoa. The first study explored Māori patients’ and whānau (extended family or social grouping) experiences of care (Komene et al., 2024). The second, reported in this paper, focused on Indian patients as the largest subset of the Asian population at the study site; and the third unpublished study, explored the experiences of Samoan patients. Providing patient-centred health services that are responsive to diverse populations is essential to expanding global migration and ethical professional practice (World Health Organization, 2022).

Results from the study with Māori patients and whānau offered insights into how crucial a patient’s first encounter with healthcare staff was during their inpatient episode (Komene et al., 2024). The study identified that while models of relational care, as illustrated in the western-centric FoC Framework were helpful, suggested modes of practice were missing (the how-to, or ways of doing) that could address the needs of Indigenous and other minoritised groups, such as engaging in whakawhanaungatanga (establishing relationships and relating well to others) with patients and whānau (Komene et al., 2024). Consequently, the FoC Framework was the focus of a wānanga (meeting to discuss, deliberate, debate and consider ideas in-depth) attended by Māori leaders and a range of health professionals from all disciplines (Pene et al., 2024).

A key recommendation from the wānanga was for the FoC Framework to be applied alongside a mode of practice that emphasises Māori values and practices such as whakawhanaungatanga and manaakitanga. This recommendation aligned with Komene et al.'s (2024) suggestion that a relational mode of practice underpinned by Māori values and practices would “better meet the needs of Māori engaging with acute healthcare services so that fundamental care can proceed” (p. 1556). Participants in the Komene et al. study noted the changing workforce, which included internationally qualified health professionals, as not being reflective of Māori culture nor responsive in making them feel confident and engaged. They also noted how busy staff were, seemingly lacking time to engage in good communication and the ability to whakawhanaungatanga, considered essential for quality care (Komene et al., 2024).

Time, busyness, and the work environment are frequently referred to regarding nursing and missed nursing care (Griffiths et al., 2018; Recio-Saucedo et al., 2018). Missed nursing care is defined as “any aspect of required patient care that is omitted (either in part or in whole) or delayed” (Kalisch et al., 2009, p. 1509), such as personal hygiene, skin care and assistance with food and hydration, amongst others, and is linked to critical incidents, higher readmission rates, and patient mortality (Griffiths et al., 2018; Jackson, 2023; Recio-Saucedo et al., 2018). Over twenty years ago missed care in Aotearoa New Zealand was identified using the following four categories, “unduly delayed, e.g. pain medication; care delivered to a sub-optimal standard, according to professional consensus and best practice; care inappropriately delegated to someone not trained to perform the activity or for whom the activity falls outside their scope of practice; and care that is omitted completely” (McKelvie, 2011, p. 34). Four years later, the implementation of a Care Capacity Demand Management (CCDM) programme identified that care was indeed rationed or ‘missed’ (O’Connor, 2014). More recent work has identified the concepts of both time and busyness, as barriers to good communication and as barriers to nurses establishing meaningful relationships with patients (Dewar et al., 2023; Jackson, 2023).

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore the four areas identified for improvement from the measurement and evaluation peer-review programme and then to understand how the actions of nurses as caregivers as identified in the FoC Framework, impacted on the fundamental care experiences of Indian patients engaging within an acute health care organisation in Aotearoa New Zealand. Indian patients were selected as the target population for the study because they represented the largest subset of the Asian category at the study site. Exploring the caregiver actions of nurses, as identified in the FoC Framework, alongside patient experiences, can provide insight into how to deliver quality care. This study is the first in Aotearoa New Zealand to explore the experiences of Indian patients using the FoC framework.

Aim and objectives

This study aimed to understand the inpatient experiences of Indian people accessing acute hospital care in Aotearoa New Zealand, using the Fundamentals of Care Framework and specifically focusing on communication, respect, personal care and self-care.

The objectives were 1) to understand Indian patients’ experiences as recipients of care delivery concerning communication, respect, personal care, and self-care, and 2) to identify the impact of associated caregiver actions.

METHODOLOGY & METHODS

Design

This study used a qualitative descriptive approach, which aligns with critical theory and the view that different participants perceive reality in different ways within dynamic contexts; a philosophical approach well suited to this study (Doyle et al., 2020). The FoC conceptual framework centres on the establishment of a trusting relationship between the nurse and patient to ensure the patient’s essential physical, psychological, and relational needs are met (Kitson, 2018). The FoC Framework also identifies the necessary caregiver (nurses) actions that will result in meeting patients care needs (Figure 1). This study adhered to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines (Tong et al., 2007).

Sample

The organisation’s patient management system was used to identify a purposive sample of people who identified as Indian and had been inpatients for a minimum of three days in an acute area, for example surgery, general medicine. Length of stay in these areas ranged from 3-30 days with an average of 3.06 days. A minimum of three days stay was selected because it was expected that participants would experience a full range of inpatient care delivery over this period. The aim was to recruit a sample of 10-12 (with approximately equal numbers of male and female) participants based on the concept of information power. For planning purposes, it is necessary to provide an approximate sample size but the final sample can be reviewed throughout the research process dependant on the information provided (Malterud et al., 2021). Information power is obtained by the information the sample holds, including how relevant it is for the study based on, 1) the aim of the study; 2) sample specificity; 3) the use of established theory; 4) quality of dialogue; and 5) analysis strategy (Malterud et al., 2016). The study’s aim, sample specificity, use of established FoC theory, anticipated quality of dialogue from one-to-one interviews, and analysis strategy, suggested a sample of 10-12 participants would be sufficient to provide the power enough to glean the information required to respond to the aim of the research (Malterud et al., 2016). Specificity was achieved by ensuring participants belonged to the target group being studied and reflected the study aim, in this study Indian people who have experienced care delivery in an acute hospital.

Ethics

Ethical approval was provided through the Auckland Human Ethics Committee, Reference Number AH23032, dated 14/10/2021, and locality approval was given from the study site on 15/11/2021, Registration Number 1513. Written information about the study was emailed to participants before they chose to participate along with consent forms. Consent was sought verbally before the telephone interviews. Identifying information was removed from transcripts to ensure confidentiality, quotes are reported using pseudonyms. All participants received a gift card as koha (gift) acknowledging their time and appreciation for their knowledge sharing.

Recruitment

Potential participants were approached by research team members AG, EK and provided information about the study via telephone. Participant information sheets and consent forms were emailed to those who expressed interest. A date was set to explain the documentation and with their consent, conduct the interview. The total sample size was 668 after the inclusion criteria were applied. Fifty-six calls were made to achieve a sample of ten participants. Reasons provided for declining to participate included, being too busy, working, and caring responsibilities.

Inclusion criteria

-

Must identify as Indian.

-

Recent inpatient (6 - 12 months)

-

English-speaking or with a support person to translate.

Exclusion criteria

-

Non-English speaking without access to an interpreter.

-

Patients/family who cannot give informed consent.

Data collection

Face-to-face individual interviews were chosen as the method of data collection; however, due to COVID-19 restrictions, interviews were offered via telephone or video call, depending on the participant’s preference. A research team member who identified as Indian AG interviewed the participants. All interviews were conducted via phone using a semi-structured interview guide informed by the previous peer review and the areas of least satisfaction for Asian patients. Interviews ranged from 20-45 minutes, were audio recorded and transcribed by an organisational transcriptionist.

Data Analysis

Directed content analysis was applied to the data which is a qualitative deductive method that analyses information guided by pre-existing categories (Armat et al., 2018). Categories were drawn from the areas of improvement identified in the peer review and in the FoC Framework that were explored in more depth in this study: 1) communication, 2) respect, 3) personal care, and 4) self-care. These aspects were used to create a framework, then transcripts were searched for content related to or associated with these four aspects. Illustrative quotes were drawn from the data to add richness to the narrative.

The data drawn from this first step of the analysis was then considered through the lens of caregiver actions as identified in the FoC Framework. Data drawn from this process was organised under the four predetermined codes and then reported under the associated nurse action category. This method of content analysis provides space for inductively derived data to create new categories if important findings are revealed that do not fit predetermined categories (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). Three authors AG, CA, EK, listened to the interviews and reviewed each interview transcript deliberating and taking notes of our impressions and observations to gain familiarity with the data. Next, two authors KK, CA, applied the directed analysis described above and began organising the data into a predeveloped framework. Other inductively identified themes not accounted for within this framework were noted. The framework and illustrative quotes were refined further by CA. Participant quotes were included to support credibility. On completion, the framework was shared with other team members to reach a consensus. To establish confirmability, each iteration of the deidentified analysis was stored in a file accessible to all team members so they could continually review and raise any questions.

Rigour and reflexivity

Ensuring trustworthiness requires a study to demonstrate credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability (Lincoln & Guba, 1986). Having a diverse research team contributed to reducing bias and ensuring credibility as did acknowledging how our own culturally diverse backgrounds impact our worldviews. The team involved in data collection and analysis all worked in, or with, the patient experience team and included a Māori nurse research assistant with experience in qualitative data analysis, an Asian health advisor who migrated to NZ as a child and is a consumer expert, an Indian nurse educator involved with education and clinical care, and a doctorally prepared nurse who is a mixed methods researcher and migrated from England eighteen years previously. To ensure transferability and dependability, we clearly described the recruitment process, participant characteristics, data collection and analysis process and our theoretical grounding in the FoC point of care theory. This means the study’s transferability to other contexts can be easily assessed.

FINDINGS

Participant characteristics

Ten participants were interviewed with an average age of 42 years (range 31-53 years). One participant spoke on behalf of their family member. Equal numbers of men and women were recruited, and they represented seven different clinical specialities, see Table 1.

The data were organised under the categories in the framework which directed the content analysis: communication, respect, personal care and self-care. They were then connected to the appropriate caregiver action drawn from the FoC Framework: 1) active listening, supporting, and involving families; 2) engaging with patients; 3) helping patients to cope; 4) working with patients, self-care, setting goals and being present. A fifth category was identified inductively through the data, which was titled the impact of busyness. See Table 2

Active listening, supporting, and involving families: Communication

Some patients expressed how they felt listened to and understood, which helped to direct their care. They described being listened to as the best thing that can happen for patients:

They were listening, the doctors and nurses they were listening to me. That’s the best thing that a patient needs for me, listening, so they know what I am going through and guide me and care for me they asked me about my health, and we had a discussion. [JA]

The same patient then further explained how they were unable to see their young son while in hospital because of the COVID-19 restrictions in place. The rationale for restricted visiting was clearly explained to the patient, who understood and therefore did not question the situation; however, they were terribly upset at not being able to see their child:

"They explained to me why [my son could not visit], but it was still upsetting. They [the nurses] explained it was protocol, we can’t have kids around. It wasn’t comfortable, to be honest… I understood that’s why I didn’t say anything more. [JA]

Other participants were appreciative of the nurses who helped teach correct donning and doffing of the personal protective equipment (PPE) for their relatives, describing how friendly they were and how they listened to both the patient and their relative. One participant reported how nurses explained what they were doing to them, which helped to relieve their anxiety:

The staff was very good… they explained what they did to me, everything was explained very nice, and I didn’t get anxious. [GA]

However, one family member described how they encountered staff who struggled to communicate with their relative who was cognitively impaired. Throughout the interview, they expressed their frustration at the communication breakdown and minimal use of other strategies to gain essential information about the patient and their condition which led to a distressing experience:

It was really concerning. If I wasn’t there, she wouldn’t have known, and she would have just agreed. Her IQ [intellectual capability] is not that great, that’s why she doesn’t understand things and hence why I support her with things like that. It has been really concerning with her hospital admissions…. Read through the notes and check with us, you know if we’re there, or check with the doctors before doing any other procedures or any other medical intervention. [EA}

The importance of including family in communication was a thread throughout the interviews but as illustrated in the participant quote below, this did not always go well. The patient suffering from severe nausea and vomiting had to stand their ground to have their relative’s voice heard and acted upon, as part of their treatment plan:

My mother is a doctor back in India, she talked to some of her colleagues they told me that one of the medicines that is being given orally to me should be given by IV [intravenous]…. I had to take this up and like argued with the nurse and everyone around me to give that medicine through IV. Finally, I managed to get it through IV and within a few hours my symptoms resolved. [TM]

Engaging with patients: Respect

Participants reported a sense of belonging, created through the displays on the walls providing culturally relevant information for this population group, acknowledging their culture within the care environment. Additionally, participants saw their own culture and ethnicity reflected in the workforce and it made a difference to them:

I felt I quite belonged to the ward because the wall displays had a lot of cultural information… A dynamic mix of staffing in the ward as well… it was very helpful having so many different people from other cultures there. I did not feel that at any stage I didn’t belong. it was good. [KM]

Some people belonged…to my culture, my religion, they know everything, everyone is very friendly and know about the cultures because we are multicultural. [DH]

On a less positive note, many participants commented on the numerous occasions they were left waiting for several fundamental care needs. Sometimes it was to get to a bed in the right ward, waiting for water, medication, or even to go home:

Sometimes you know they [the nurses] take too long, like you know when you go there, they shift you so many places one by one then after that on the third day they take you to a proper place and they make you stay there and do all the check-ups then. [MJ]

The same participant described the long wait for nurses to respond to call bells which made them feel bad:

When I used to ring also, they used to come after 45 minutes [waiting]. It feels bad you know [MJ]

They were looking after me, but sometimes I must wait for them for a long time. When the pain starts, I ring the bell and they come late, to my bed. [JJ]

One participant described having to stay over the weekend because there were no doctors available to discharge them on a Friday; the consolation was the nurses were respectful and courteous:

The ward I was in was amazing. I think all those nurses that came around were very, very respectful and they took very good care. I was intending to go home on Friday, but I had to stay until the weekend because there were no doctors. [KM]

Helping patients to cope: Personal care

Other situations included patients who were uncomfortable with the cleanliness and lack of control over their environment. Using shared toilets was a problem particularly at night when there were no cleaners. The nurses assisted one participant to locate other bathrooms beyond their allocated room. When asked how a hospital experience could be improved the participant stressed again how important a clean and neat environment was when a person was feeling sick.

I can understand that because there are three old patients and they are really struggling. One person was also very old, and he was also using the washroom I went to another toilet and I used that toilet when it was not clean. [JC]

You want to have cleanness all the time, everything should be neat and clean because it is a hospital, especially in the night, I think there’s no cleaners and stuff… I didn’t feel I could tell them [the nurses]. I thought that they are going to mind if I tell them something, so I just kept quiet. [MJ]

Working with patients, self-care, setting goals and being present: Self-care

Participants describe the importance of family assistance during their stay in relation to personal care, either because staff are busy with other patients, or it was comforting and preferable for the patient:

Because there’s less staff when my husband is with me it is very good for me because sometimes, I have walking problems when I’m going to the washrooms. I ring the bell button, but the nurse is busy with someone else. [DH]

One participant described how they were provided with the appropriate food which was important to them and made them feel respected. Other patients also described having good food, but with little thought given to the patient’s condition or ability to eat it:

I didn’t feel like complaining, the food they [the hospital] were providing me was good but due to my condition of having severe nausea and vomiting, I couldn’t eat it. So, my point is the food was good, but it should be given on patient-to-patient basis. [JM]

It was apparent that nurses worked with patients and their families to help them achieve self-care tasks, particularly their hygiene needs. However, there was a failure to anticipate nutritional needs or comfort when providing meals for nauseous patients.

The impact of busyness

There was an undercurrent of the impact of nursing busyness weaving through the interviews which can be seen in several of the quotes above. Patients tried to offset this busyness by having family members help care for them as DH had explained when her husband was there to help her. Participants were reluctant to criticise nurses describing their care as ‘good’ even when they waited unacceptable lengths of time for pain relief or to speak to a nurse. There was an unassailable sense that participants felt and experienced the busyness of nurses and excused failings in their care because of this, one example being JJ who described how while the nurses were looking after them, they took a long time to respond.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to understand the inpatient experiences of Indian acute hospital service users and the impact of nurses’ actions using the FoC Framework as the underpinning theory. The objectives were to 1) understand Indian patient experiences as recipients of care delivery concerning four a priori categories of communication, respect, personal care and self-care, and b) to identify the impact of the associated relational caregiver (nurses’) actions as identified in the FoC Framework. A fifth category was discovered in the data weaving through many of the interviews, this was the impact of nursing busyness which is explored in more detail in this discussion.

Findings revealed participants separated their physical and psychosocial care when reporting their experiences. Regarding communication, they conveyed staff were good at listening to discussions about their physical healthcare needs, yet they were not able to discuss feelings of distress at being separated from family. The patient, however, described this as a “good care experience,” which we suggest is an example of patients’ adapting and reflecting back nurses’ prioritisation of ‘necessary tasks.’ According to Aiken et al. (2012) necessary tasks do not include time for trusting conversations and providing comfort. The relational caregiver action of integrating care and anticipating the patients’ needs identified in the FoC Framework was missing from this event and the absence of fundamental physical, sociocultural and emotional care is described in the literature as care failure (Dewar et al., 2023; Feo & Kitson, 2016). Had the nurse anticipated how the separation impacted the participant’s emotional well-being and practised active listening, they may have developed a relationship that encouraged, open communication allowing the patient to discuss their feelings.

Anticipating the need, active listening, helping patients to cope, supporting, and involving families, are all identified as caregiver actions in the FoC Framework, which directs nurses to action, or ‘ways of doing’ fundamental care. The tenets of fundamental care include developing positive and trusting relationships while attending to both physical and psychosocial needs, essentially, the integration of care (Kitson et al., 2019). Failing to deliver psychosocial care such as comforting, talking and anticipating patient needs beyond their physical health, is ‘missed care’ and psychosocial care is the care most frequently missed (Griffiths et al., 2018). The prioritisation of physical care, deference to medicine, staff shortages, lack of time, and busyness, have all been reported as reasons for missed psychosocial care (Dewar et al., 2023; Papastavrou et al., 2014; Recio-Saucedo et al., 2018). It is concerning that patients too, have learned to separate their physical and psychosocial needs when assessing the quality of their care.

Similarly, anticipating, knowing, supporting, and involving families was frequently absent from the care experience in this study. This was highlighted in the care of a cognitively impaired person who was unable to communicate with staff effectively. Taking time to get to know the patient did not occur, working with the patient and family to set goals, appears absent from the patient and family perspective, and there was little anticipation of patient need, before delivering care. The involvement of family in care has been reported as essential for this and other population groups (Pene et al., 2023; Singh et al., 2022).

Establishing relationships and trust would have enhanced the care experience of the patient whose mother was a doctor to discuss treatment options which eventually resolved the patient’s physical needs. The resulting lack of confidence in staff by the participant of this study here, echoes the experiences of Māori patients at the study site (Komene et al., 2024) and reaffirms the critical nature of whakawhanaungatanga (establishing relationships and relating well to others) in a healthcare partnership with nurses, patients and whānau (family or social grouping). Intentional relationship building is critical and can be achieved through the whanaungatanga (respectful and reciprocal relationships) which is recommended as a mode of practice essential prior to beginning care delivery (Komene et al., 2024). Lack of relational care contributes to poor experiences for Māori and others (Pene et al., 2023).

Respect for patients should be evident in the environments we provide, enabling patients to feel safe. The maintenance of a clean environment was identified as important to participants but often did not occur, particularly during the evening when there were fewer cleaning staff. The impact of the context of care should not be underestimated with environment-related barriers reducing access to care (Kwame & Petrucka, 2021). Poor ward conditions are reported to affect patients’ psychological state, create barriers to communication and leave patients feeling disrespected and consequently impacting nurse-patient relationships (Kitson et al., 2013; Kwame & Petrucka, 2021). Armed with this knowledge, nurses in Aotearoa New Zealand can draw on their codes of conduct which state they must “take steps to ensure the physical environment allows health consumers to maintain their privacy and dignity” (New Zealand Nursing Council, 2012, p. 9). This situation highlights how nurses need organisational investment in resources to fully support the integration of fundamental care, which includes the physical, psychosocial, and contextual domains (Pattison & Corser, 2023).

Relational care, as advocated in the FoC point of care theory, is effective when implemented correctly, as shown by certain participants in this study. Patients’ anxieties were relieved when they and their families were supported by nurses with donning and doffing PPE. Most participants said they felt well cared for, which aligns with participant experiences in Singh et al.‘s (2022) findings from Indian stroke patients’ experiences in a hospital in Aotearoa New Zealand. Singh and colleagues’s study identified four themes including helping self-care, family and support, social connections, and identified that ethnicity was not a barrier to their care. Cultural differences and ethnicity were not reported as an issue within the context of care for this study. Participants expressed experiencing a sense of belonging which was attributed to identifying with members of the workforce who were also from India. The importance of the environment and context of care was highlighted by participants as the wall displays which were reflective of Indian culture were appreciated by the participants. This contrasts, yet reaffirms, the experiences of Indigenous participants from the previous study who were cognisant of the lack of representation of their culture within the workforce which they believed impacted their care (Komene et al., 2024).

Aotearoa New Zealand overall, has one of the highest numbers of internationally qualified nurses (IQNs) in the OECD at 47% of the workforce (Nursing Council of New Zealand, 2024). Of all IQNs registered in 2022-2023, 59% were originally educated in India (Nursing Council of New Zealand, 2023), which contributed to culturally safe care for these participants who reported they had their values and beliefs reflected, considered, and respected. The number of Indian nurses within this care environment supports the cultural experience of Indian patients and families. For all the same reasons, the low numbers of Māori nurses make Māori patients feel unsafe from a cultural perspective (Komene et al., 2024). One explanation for this could be gaps in the Competence Assessment Programmes for IQNs, which reportedly did not improve their understanding of the cultural practices deemed necessary to improve equitable health outcomes for Māori (Clubb et al., 2024). For domestically trained nurses, it has been recommended that teaching fundamentals of care in a standardised way is prioritised in pre-registration nursing (Crossan et al., 2022). We would add that teaching how the impact of nursing ‘busyness’ when delivering fundamental care, affects the people and families who they are caring for, is also essential.

All participants responded positively to the question “Did you feel respected during your hospital stay,” yet several described how they experienced lengthy waits for essential items such as medication, and water, or to be situated in the appropriate place for the care they needed because nurses were busy. Participants seemed hesitant to be viewed as unappreciative of nurses and unaware of their demanding schedules. However, in India, fundamental care is often provided by families which might have affected expectations and acceptance of the standards of nursing care provided (Park et al., 2022). Despite this, a strong need for education on including the involvement of families in nursing care has been identified (Sharma et al., 2024). A strong sense of excusing nurses due to busyness was drawn from the interviews which can be linked to a culture of busyness. Busy health professionals convey a sense of hurry that is felt and experienced by others (Govasli & Solvoll, 2020). Over a decade ago busyness was identified as a discourse adopted by patients which shapes their expectations of care (Nagington et al., 2013). This phenomenon is still prevalent and has been explored prior to, and following, the COVID-19 pandemic (Simpson-Collins et al., 2024). Now that patients have taken on the burden of nursing busyness, accepting this mantra has become a “go-to” response when querying care quality (Jackson, 2023) .

Strengths and limitations

The sample size of ten participants gave a limited yet relevant perspective of Indian patient and family experiences as only they can. This perception may have been influenced by their migrant status in Aotearoa as either first or second-generation migrants to the country. The lack of information on how long they had been in the country was a limitation of the study. Further, it is usual in India for families to provide care for patients which may have impacted participants expectations of staff. Additionally, only English-speaking participants were recruited for the study which may have positively impacted their experiences in hospital.

The diversity of the research team was a strength of the study adding a culturally safe approach to the analysis and the interviews. A limitation was the inability to conduct the interviews face-to-face due to COVID-19 restrictions. However, the medium of telephone has been supported and used in previous research with Indian participants without difficulty and has been perceived to be a user-friendly interview tool (Singh et al., 2022; Ward et al., 2015). The study was performed at a hospital in Auckland with a focus on acute adult care and must be assessed in that context for its transferability.

Recommendations for further research

Fundamental care as conceptualised in the FoC Framework is a theory nurses can use to deliver quality, integrated, patient care, yet for too long, task-orientated care has taken priority, to the point where patients no longer anticipate nor expect integrated physical and psychosocial care. The burden of busyness is a phenomenon that needs further exploration from the perspective of patients and consumers of health care. Findings from this study indicate that nurses may not understand the importance of the ‘how to’ when delivering the relational caregiver actions of the FoC Framework, which warrants further exploration. Further recommendations include consideration of different population groups crossing the life span, and those in different settings, such as mental health and the community.

CONCLUSION

The objective was to understand the experiences of fundamental care delivery and the impact of caregiver (nurses) actions on Indian patients and families. Participants did not relay any differences in care related to their culture or ethnicity, the diversity of the workforce reflective of themselves, was a welcoming factor highlighting the benefits of a globally mobile workforce. They did, however, reveal the impact of nursing busyness on their care and their expectations. Expectations of receiving relational, integrated, fundamental care appear low, and patients accept task-focused, physically focused, health care. The interpretation of the results from this study suggests that participants have taken on the burden of nursing busyness which is a barrier to the delivery of relational integrated fundamental care.

Funding

This study was funded by the Te Whatu Ora Counties Manukau TUPU Fund.

Conflicts of Interest

EK is an assistant editor on Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand