INTRODUCTION

Te Whatu Ora (Health New Zealand) Waikato is a large regional hospital in Aotearoa New Zealand that provides services to approximately 425,000 people at seven sites across the region (Ministry of Health, 2022). There is a contractual obligation to provide clinical placements for nursing students from undergraduate programmes, in addition to the established commitment to facilitate preceptorship for new nurses and those progressing or transitioning in their clinical roles. Feedback from clinical areas conveyed concerns regarding the operational and workforce challenges associated with the traditional model of allocating a dedicated preceptor to an individual nursing student. These concerns were affirmed by connecting with nursing placement coordinators from Te Whatu Ora districts from across the country, who further expressed interest in the findings from our integrative review

BACKGROUND

Support of nursing students translating theoretical learning into clinical practice has predominantly resulted in a dedicated one-to-one preceptorship model (Omansky, 2010; Pere et al., 2022). Such a model can be challenging for preceptors who need to balance the demands of high acuity patients, increased workloads, and the responsibilities of supporting optimal learning and allowing time for students to learn at their individual pace (Pere et al., 2022). One of the key issues identified for students is the potential disruption to the continuity of preceptorship caused by factors such as days off, sick leave, and study leave. This challenge prompted a request from Te Whatu Ora Waikato nurse leaders to investigate whether alternative models of preceptorship could be employed to support clinical learning effectively while adhering to the necessary standards for nursing clinical placements.

Preceptorship is a teaching model used in the nursing profession which involves the pairing of an experienced nurse with a nursing student or a new nurse to develop clinical knowledge and skills in clinical practice (Billay & Myrick, 2008; New Zealand Nurses Organisation, 2022). Clinical teaching encompasses the same responsibilities for learners at any level, however, each learner brings their own prior educational and experiential background which may influence preceptor workload. An important aspect of preceptorship is that preceptors should be trained to teach in clinical practice to ensure patient care and safety is prioritised. Learning in clinical practice is a mandatory component of nursing education (Nursing Council of New Zealand, 2022) and preceptors are essential to support the students to integrate theory to practice, to socialise in the clinical context, and facilitate opportunities to develop skills, knowledge and critical thinking applicable to real practice (Omer et al., 2016).

Having a suite of evidence-based preceptorship approaches affords clinical providers flexibility to support alignment of preceptors with student leaning needs within various clinical contexts (Pedregosa et al., 2020). To accommodate a high number of students, clinical areas within the Waikato region have adopted varying ways of managing preceptor allocation, with most utilising a dedicated education unit (DEU) model. The definition of the DEU in the Aotearoa New Zealand context is a clinical teaching and learning model that expands on the concept of one preceptor to one student to a model where all staff offer support and learning opportunities to nursing students within clinical areas (Canterbury District Health Board, n.d.). Although each DEU may adapt the approach to meet resourcing ability, the model is based on a partnership between the clinical practice team and the academic institution whereby primarily the clinical registered nurses work with students in a team approach with clinical and academic liaison staff in support (Flott et al., 2021).

Relevance to practice

Undergraduate nursing students are integral to the growth of the nursing workforce. They require effective preceptorship to ensure appropriate translation of theoretical learning in practice and to meet the current standards of quality and complexity of patient care (Juvé-Udina et al., 2020). Developing preceptorship models to ensure the quality of clinical learning while accommodating the operational capacity has a significant impact on preparing the future nursing workforce. This integrative review aims to contribute to the development of a workforce pathway that can seamlessly integrate learning and practice in a dynamic healthcare environment. The findings of this review may inform development of future preceptorship models that afford flexibility and structure, that are responsive to clinical context, and provide clarity of the preceptorship role.

Review objective

The objective of this integrative review was to explore international research findings on different preceptor models. An initial literature exploration was undertaken by a small group of researchers representing Te Whatu Ora Waikato. The initial exploration and anecdotal conversations from clinical areas confirmed the question prior to establishing the formal search strategy. The following question informed the inquiry:

- What models of preceptorship facilitate effective clinical learning alongside the dedicated preceptor model?

METHODOLOGY

To investigate the review objective, we adhered to the integrative review framework described by Whittemore and Knafl (2005), as recommended for identifying evidence relevant to nursing practice. This process involved defining the review purpose, conducting a systematic literature search, evaluating the quality of the studies, and analysing the data to identify patterns and themes. Integrative reviews offer a structured approach for effectively exploring different perspectives, identifying knowledge gaps, and generating future research recommendations (Cronin & George, 2023). When conducted rigorously, an integrative review provides a reliable and comprehensive representation of the evidence base, thereby informing policy and practice (Dhollande et al., 2021).

Problem identification and search strategy

Preliminary searches using Google Scholar and various academic databases were conducted to gain a broader perspective on the topic, identify relevant keywords, and refine the search strategy. Using the Population-Exposure-Outcome (PEO) format (Dhollande et al., 2021), we identified nursing or nursing students as the population, the clinical learning as the exposure, and the models of preceptorship as the outcome. The term “assessment” was included in the search strategy to ensure we included the studies assessing preceptorship models.

Comprehensive literature searches of CINAHL, EBSCO, PubMed, Ovid, and Discovery databases were undertaken at Te Whatu Ora Waikato, the University of Auckland, and the University of Waikato between September 2021 and May 2024. The search comprised a combination of the following terms: “models of preceptorship,” “nurs*,” “clinical learning,” and “assessment.” Boolean operators and rephrasing of the text were utilised to refine the search and secure the most relevant results.

Inclusion criteria

-

Year: January 2017 to May 2024

-

English language

-

Primary research

-

Articles focusing on preceptorship and /or mentoring in clinical practice

-

Articles where at least one preceptorship model was evaluated

-

Articles where nursing students or nurses were the preceptees

Exclusion criteria

-

Studies focused on other types of clinical education

-

Studies that did not evaluate preceptorship models

-

Research involving preceptorship of other health professionals

-

Non-research papers, abstracts, individual reports, conference papers, secondary research, and systematic reviews

-

Articles not available in English

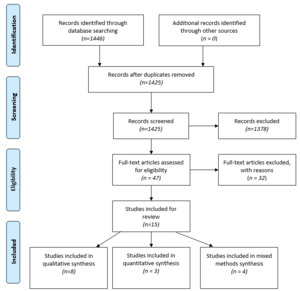

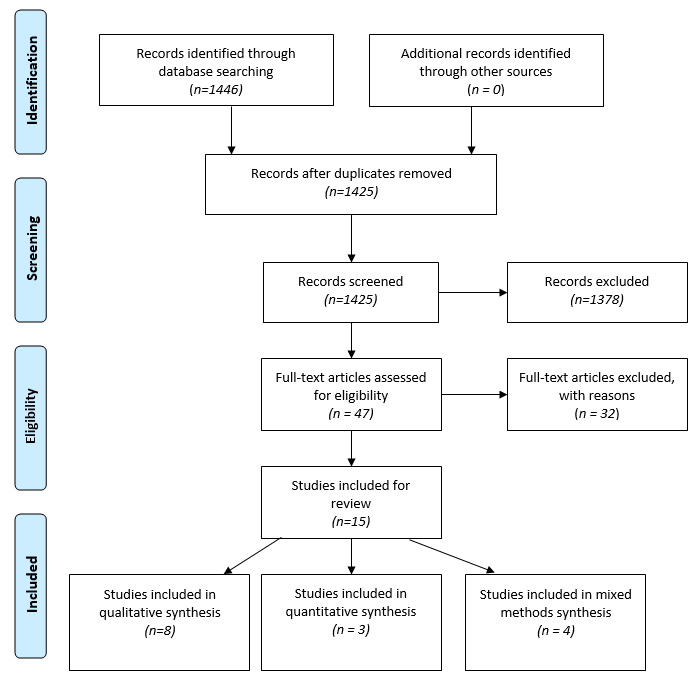

Screening and quality appraisal

The search strategy identified 1446 articles. All articles were recorded in an excel template and duplicates were removed. The screening of title and abstract resulted in forty-seven (n=47) articles selected for full text review. Three authors (MR, TI, JS) then read the articles in full and independently selected articles according to the inclusion criteria. Consensus and decision were reached in discussion with the fourth author (CA) and fifteen articles (n=15) were included in this review. The quality and methodology appraisal was done independently by two of the authors (TI, JS) using the mixed method appraisal tool (Pluye et al., 2009). All the fifteen articles met the inclusion criteria. The search results and selection of records are presented in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) diagram (Moher et al., 2009) (Figure 1).

Data evaluation and analysis

Data from the selected articles was initially organised under the following headings: study aim and participants, research methods, models of preceptorship, limitations and strengths and key findings. Three authors (MR, TI, JS) reviewed, compared and regrouped the data and reached consensus on the categories displayed. This was further refined to the format presented in the summary of evidence table (Supplementary File 1).

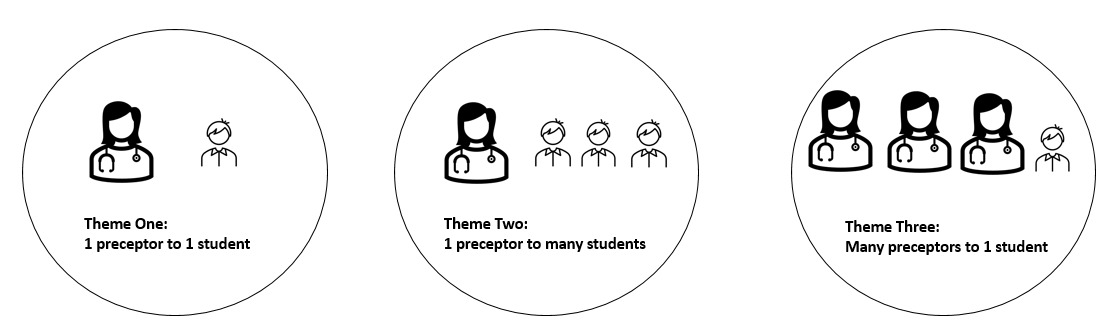

The research used a thematic analysis approach as outlined by Braun and Clarke (2022). This involved a systematic process of data familiarisation, coding, and organising, followed by the refinement and development of themes aligned with the research question. The same three authors (MR, TI, JS) engaged with the data through multiple readings to identify key features relevant to the research question. They collaboratively generated codes, which were consistently applied throughout the analysis. These codes were then further refined into emerging themes by focusing on their core characteristics leading to the identification of three central models. The three main models of preceptor allocations: 1) one preceptor to one student; 2) one preceptor to many students; 3) many preceptors to one student.

RESULTS

Study characteristics

Half of the articles (n=8) reported qualitative studies (Boardman et al., 2018; Borren & Harding, 2020; Grealish et al., 2018; Hanson et al., 2018; Jassim et al., 2022; Kjällquist-Petrisi & Hommel, 2021; Nygren & Carlson, 2017; van der Riet et al., 2018). Three reported on quantitative studies (Ekstedt et al., 2019; Frie et al., 2020; Johannessen et al., 2021) and four used mixed methods (DeMeester et al., 2017; Hill et al., 2020; Lindell et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2021).

The qualitative studies involved semi structured interviews (Hanson et al., 2018; Jassim et al., 2022; Kjällquist-Petrisi & Hommel, 2021; Nygren & Carlson, 2017; van der Riet et al., 2018), focus group discussions (Boardman et al., 2018; van der Riet et al., 2018), learning groups discussions (Grealish et al., 2018), and data from project implementation and interviews (Borren & Harding, 2020). The quantitative studies used clinical learning environment and nurse teacher evaluation (CLES+T) (Johannessen et al., 2021); and in combination with a self-developed questionnaire (Ekstedt et al., 2019); and an additional pre and post clinical nurse teacher survey (CNTS) (Frie et al., 2020). The mixed method studies used combinations of open-ended survey and private telephone interviews (DeMeester et al., 2017); student survey (Lindell et al., 2018); and individual survey, focus group questionnaires and semi-structured interviews (Hill et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2021).

Study settings and samples

The studies selected were published between 2017 and 2022. The study locations included five studies from Europe (Ekstedt et al., 2019; Jassim et al., 2022; Johannessen et al., 2021; Kjällquist-Petrisi & Hommel, 2021; Nygren & Carlson, 2017), three from the United States of America (DeMeester et al., 2017; Frie et al., 2020; Lindell et al., 2018), three from Australia (Boardman et al., 2018; Grealish et al., 2018; van der Riet et al., 2018) and one from each of the following countries: Canada (Hanson et al., 2018), England (Hill et al., 2020), New Zealand (Borren & Harding, 2020) and the United Arab Emirates (Williams et al., 2021).

Study participants

The majority of studies examined the experience of different levels of preregistration undergraduate nursing students and preceptors in clinical practice. Seven studies included Bachelor of Nursing (BN) students from various levels: second year (Ekstedt et al., 2019; Jassim et al., 2022; Johannessen et al., 2021; Williams et al., 2021); third year (van der Riet et al., 2018); fourth year (Frie et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2021); and master of entry to nursing practice (Lindell et al., 2018). Two studies conducted surveys across all levels of BN students (Grealish et al., 2018; Hill et al., 2020), while De Meester et al. (2017) focused on first- and second-year undergraduate baccalaureate students.

Six studies (Boardman et al., 2018; DeMeester et al., 2017; Hanson et al., 2018; Jassim et al., 2022; Nygren & Carlson, 2017; Williams et al., 2021) presented data gathered from registered nurse preceptors of undergraduate students while Kjällquist-Petrisi and Hommel (2021) examined the experience of preceptors of postgraduate nursing students. Additionally, one study (Frie et al., 2020) included the perspective of social workers serving as preceptors for nursing students, specifically within the context of public health.

In terms of stakeholders’ perspectives, three studies (Borren & Harding, 2020; DeMeester et al., 2017; Grealish et al., 2018) presented insights from various stakeholders, including faculty members, academic staff, and a DEU working group.

FINDINGS

The findings highlighted diverse preceptorship approaches in clinical practice to support effective learning for undergraduate and postgraduate students. These methods were influenced by preceptor availability, student numbers, and challenges such as workload acuity and staff shortages. Team-based strategies, involving collaboration among preceptors or student groupings, with or without academic or clinical coaching support, emerged as a common solution. Additionally, preceptorship models were tailored to the specific requirements of clinical settings. For example, primary care integrated multidisciplinary team members, while intensive care and mental health settings adapted preceptorship to their unique nurse-to-patient allocation demands.

The identified themes correspond to three distinct models of preceptorship that are applicable for allocating preceptors to students during clinical placements. These are illustrated in Figure 2.

-

Theme One: One preceptor to one student. One preceptor works with one student over the course of a shift. One preceptor will predominantly work with one student over the duration of their placement.

-

Theme Two: One preceptor to many students. One preceptor works with two or more students over the course of the shift. That preceptor will work with many students over the duration of the placement.

-

Theme Three: Many preceptors to one student. Two or more preceptors work with one student over the course of the shift. Many preceptors will work with one student over the duration of the placement.

Theme One: One preceptor to one student

Regarding the preceptor role, Hill et al. (2020) found preceptors were able to provide more direct supervision, which Ekstedt et al. (2019) discussed as intensive preceptorship. They highlighted how the model can offer more personalised supervision and create positive opportunities for students to enhance their problem-solving abilities and achieve their learning objectives. Hill et al. (2020) noted that students did not perceive substantial enhancements in their skills or capabilities under this approach. In comparison to other models, the one preceptor to one student model provided the least opportunity for students to practice independently and failed to foster an increased sense of responsibility (Hill et al., 2020; van der Riet et al., 2018).

Hill et al. (2020) discussed that staffing levels in the clinical area influenced the workload allocation to students who would benefit from lower acuity patients. Additionally, a familiarity with the preceptor and welcoming atmosphere contributed to student’s confidence and acceptance. When students were able to develop supportive relationships they fostered a sense of belonging, reducing stress (van der Riet et al., 2018). Further, students were able to confirm their rosters early, arrived at placements less anxious, and felt supported.

In their respective studies, Ekstedt et al. (2019) and DeMeester et al. (2017) emphasised the significance of educational partnerships within clinical areas in facilitating the practical application of students’ knowledge in real-world contexts. These collaborations were identified as a fundamental cornerstone for bridging the gap between theoretical learning and its practical application. However, it is essential to recognise that when collaboration and engagement in the partnership is well resourced, it impacts positively on student interaction and personalised support.

Theme Two: One preceptor to many students

The allocation of one preceptor to many students during a shift highlighted the value of the nurse in the role as preceptor, whose knowledge and clinical insights created effective learning opportunities for students (DeMeester et al., 2017). These conditions proved instrumental in fostering the development of students’ confidence, which Hill et al. (2020) found enabled students to gain a comprehensive understanding of the nurse’s role. Further, this model facilitated peer coaching where students felt comfortable asking one another questions and had an opportunity to learn and teach each other (Borren & Harding, 2020; Hill et al., 2020; Jassim et al., 2022). In this setting it was easier for preceptors to assess student progress in practice by observing their interaction while working with peers (Nygren & Carlson, 2017). Later level students could role model to those earlier in their programme and students could take responsibility for their own learning, including informing preceptors of their learning needs (Hill et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2021). However, they also found that students’ compatibility and collaboration could be compromised when students held different perspectives, learning needs, ambition and competence.

Hill et al. (2020) identified the significance of preceptors understanding the expectations associated with both their own roles and those of the students and the importance of educators in upskilling preceptors. Nevertheless, an essential factor contributing to the model’s success was the staffing levels. Short staffing meant preceptors faced increased pressure to handle a heavier workload and greater responsibilities, leading to feelings of inadequacy and heightened stress (Nygren & Carlson, 2017). The time-consuming nature of teaching and supervising multiple students, especially in relation to workload and staffing, played a crucial role, impacting the choice between dedicating time to teaching and delivering nursing care to patients (DeMeester et al., 2017). This dilemma could potentially result in students being left unattended, as highlighted by Williams et al. (2021).

Borren and Harding (2020) argued this model accommodated a higher number of nursing students in placement. Hill et al. (2020) further discussed student levels and numbers within this context, noting that facilitating student allocation was necessary to alleviate competitiveness among the students. Jassim et al. (2022) also found the planning and structure of students’ allocation provided equal learning opportunities. The increase in responsibility promoted peer-learning between the students and problem-solving skills (Kjällquist-Petrisi & Hommel, 2021). Conversely, not all students were comfortable with peer collaboration. The level of collaboration was affected by the level or experience of the student and length of time in placement (Kjällquist-Petrisi & Hommel, 2021).

Williams et al. (2021) found that early level students had attitude challenges and were ‘scared’ to implement direct nursing care, encountering experiences that were uncomfortable, stressful, and traumatising. While later level students were interested in learning and participating, wanting hands-on experiences. Students felt they would benefit from working with a consistent preceptor (Borren & Harding, 2020) where Ekstedt et al. (2019) reported students worked autonomously and perceived a sense of independence while working with different preceptors.

Several studies have emphasised the critical role of educational support staff such as educators, coaches and faculty supporting students and preceptors in clinical practice. Borren and Harding (2020) highlighted that the consistency of educational support members significantly impacts the student’s feedback and learning opportunities. Likewise, Williams et al. (2021) underscored the need for enhanced involvement of clinical faculty, emphasising its importance in supporting preceptorship.

Theme Three: Many preceptors to one student

The involvement of multiple preceptors had a positive impact when professionals collaborated and supported each-other to facilitate learning experiences (Ekstedt et al., 2019; Kjällquist-Petrisi & Hommel, 2021). Effective collaboration and communication between preceptors and students was essential in setting up trust in the relationship where the preceptor could delegate responsibility. However, clear behaviour expectations had to be set from the start to foster the student’s sense of independence (DeMeester et al., 2017). When preceptoring postgraduate students, preceptors were able to relinquish some oversight allowing students to work more autonomously (Kjällquist-Petrisi & Hommel, 2021).

With flexibility of preceptors the students had freedom to arrange their own schedules (Boardman et al., 2018; Lindell et al., 2018). The flexibility of choosing their preferred shifts helped students effectively manage their personal, work and study responsibilities which appeared to correlate with lower student absenteeism rates. According to Boardman et al. (2018) the use of many preceptors introduced variety in students learning experiences and exposure to different patient situations while the preceptor’s range of teaching styles and expertise enhanced their educational journey. However, Boardman et al. (2018) also noted there were gaps in learning opportunities due to shifts and days between experiences hindering continuity of learning for students and lack of student nurse consistency for clients.

Preceptors would partner with faculty to identify learning opportunities and found satisfaction working with students when empowered to discuss issues directly with students (Frie et al., 2020). While preceptors were excited to be shaping the experiences of students (Hanson et al., 2018), they expressed uncertainty about their role (DeMeester et al., 2017) and were unable to recognise their contribution to student learning (Hanson et al., 2018). Preceptors found if students did not take responsibility, patient safety became a concern (Kjällquist-Petrisi & Hommel, 2021) resulting in preceptors’ moral distress (Hanson et al., 2018).

Challenges of the many preceptors to one student, included having to repeat information, difficulty in evaluating students (Boardman et al., 2018; Grealish et al., 2018), lack of clarity between student expectations and competencies (Hanson et al., 2018), and confusion regarding learning needs of students and preceptors’ responsibilities (Grealish et al., 2018). Conversely, Johannessen et al. (2021) explored a dual preceptor model and found it did not detrimentally affect the ability to assess students.

Preceptors found it difficult to accommodate students in physically cramped environments and there was competition with students for space and resources, such as chairs and computers (Hanson et al., 2018). They also perceived a burden of competing responsibilities, particularly when balancing the needs of students, clinical workload demands, and patient acuity. Preceptors’ attitudes toward students, however, varied depending on the students’ level and length of time in placement (Hanson et al., 2018). At an organisational level, Lindell et al. (2018) found recruitment costs were reduced and there were less preceptors required to accommodate the students in practice.

DISCUSSION

Based on the examination of fifteen articles, this review’s objective was to identify what models of preceptorship facilitate effective clinical learning alongside the dedicated preceptor model. The results explored attributes of preceptorship models to inform current Aotearoa New Zealand practice and suggest that the array of preceptorship approaches employed in healthcare can be categorised into three overarching themes presented in this review, each possessing benefits and challenges.

The dedicated preceptor model described in theme one is appropriate for the last clinical placement where assessment of competence in readiness for becoming an independent registered nurse is important. For students that may show signs of underperforming, the continuity of a single preceptor is ideal to track improvements and work in partnership to adapt the learning objectives. This is a valuable model due to preceptor continuity, which enables assessment and relationship building (Ekstedt et al., 2019; Pere et al., 2022; van der Riet et al., 2018).

However, workforce challenges including the COVID-19 pandemic, chronic short-staffing, pay inequities, and competing clinical demands (Kurtzman et al., 2022) have led to difficulties in achieving this dedicated preceptor model. To overcome these challenges clinical areas have adjusted the one preceptor to one student model to accommodate students learning in practice leading to the uptake and development of DEU-type practices.

Themes two and three are most aligned with the DEU approach and offer several advantages for preceptorship in clinical areas that accommodate a high number of students at various stages of clinical learning. Noted advantages of theme two included peer learning opportunities where multiple students could share their experiences and insights (Borren & Harding, 2020; Ekstedt et al., 2019; Hill et al., 2020; Jassim et al., 2022; Nygren & Carlson, 2017). This collaboration supported discussions between individuals or groups of students, leading to critical analysis and reflection in practice. Students could become more autonomous in their practice which can empower students to make clinical decisions under the guidance of their preceptor (Borren & Harding, 2020; DeMeester et al., 2017; Kjällquist-Petrisi & Hommel, 2021; Nygren & Carlson, 2017).

Theme three promotes flexibility for students to collaborate with different nurses, gaining exposure to diverse personalities and work styles. This approach allows students to maintain stable shift patterns while nurses continue alternating shifts, resulting in quicker integration into the wider team as students are assigned different nurses each shift (Boardman et al., 2018; DeMeester et al., 2017; Ekstedt et al., 2019). The advantages of exposure to various preceptors became evident as students interacted and gained experience with a wide range of nursing professionals. This departure from preceptor continuity was justified by the students’ benefits from exposure to a variety of nurses (Boardman et al., 2018). Additionally, dedicating extra time and resources to areas operating as a DEU model, along with academic liaison nurses, ensures continuity and oversight (Hanson et al., 2018; Johannessen et al., 2021) typically associated with the 1:1 model, ensuring ongoing assessment of students’ competence and development (Borren & Harding, 2020).

In areas not identified as DEUs, applying theme one and three retains preceptor knowledge to provide personalised feedback for the student. Assessment of the student’s competence is a complex endeavour with the preceptor and the faculty member requiring close oversight to ensure the student is progressing through their goals to meet assessments and evaluations (Grealish et al., 2018). This is challenging to achieve if the personnel involved is changing, therefore a consistent collaboration between preceptor and faculty member supports efficient evaluation of student performance (Borren & Harding, 2020; Johannessen et al., 2021).

Within the articles the involvement of nurse educators and faculty members (clinical academic/clinical tutor/academic liaison) varied across the clinical areas. While this review is not specifically about these roles it is noteworthy that they influence the way that preceptorship occurs. Mhango et al. (2021) recognises that infrequent supervision or lack of support from faculty members make it difficult for preceptorship goals to be met. For this reason, clarity about their contribution within the structure and expectations of each role is a recommendation. Evidence arising from local student evaluations using the CLES+T tool (Mueller et al., 2018) support the need for clarity.

Students come to clinical placements with diverse backgrounds, knowledge levels, and skill sets. The optimistic attitudes displayed by students can influence the motivation of both themselves and their preceptors. According to Needham and van de Mortel (2020), students who demonstrated engagement and a readiness to learn are viewed as more receptive to support and progress. Preceptors must be willing to adapt to individual learning needs of students in real-world settings. Providing personalised support and tailored education requires careful consideration, time, and confidence from the preceptor. However, many preceptors undertake their roles without prior training, which poses a significant barrier to adequately supporting students’ learning (Needham & van de Mortel, 2020). Further, preceptors expressed a need for clearer role definitions, as well as assessment tools to support their effectiveness in achieving the learning objectives.

Nursing is marked by its high-stress nature which underscores the critical importance of preceptorship and supporting students and new nurses to gain knowledge and achieve clinical competence. This emphasis is not only vital for patient safety but also for the overall well-being of nurses themselves. Healthcare settings often grapple with challenges such as high patient acuity, staff shortages, and resource limitations, all of which can directly affect nursing care quality and patient outcomes (Juvé-Udina et al., 2020). However, the additional responsibility of preceptorship can weigh heavily on nurses, particularly when it’s layered onto already demanding workloads (Needham & van de Mortel, 2020). Despite the potential for students to alleviate some of this workload and contribute to patient care quality, their presence can also necessitate preceptors to multitask (Fernández-Feito et al., 2023). This multitasking challenge further complicates the preceptor’s ability to effectively supervise, teach, and provide feedback, often requiring more time to complete tasks (Benny et al., 2022). Pere et al. (2022) observed that preceptors must navigate the delicate balance between fulfilling point-of-care patient obligations and dedicating time to teaching nursing students.

Implications for practice

The implementation of effective preceptor models in clinical settings has significant implications for nursing practice in Aotearoa New Zealand. These models offer real-world applications, supporting the integration of nursing students into practice environments. It is crucial that these preceptor models be continuously evaluated to ensure their effectiveness and relevance to the needs of student and healthcare providers and their implications on nursing workloads and patient safety. Strengthening the development of preceptorship programmes is essential to provide adequate support for students in clinical practice by nurse educators. Preceptors must be equipped with the necessary tools, resources, and training to guide students effectively, ensuring high-quality education and mentorship. Adequate time must be given for reflections and learning opportunities with preceptors and educators. Collaboration between academic institutions and clinical settings is essential to foster the development of students in their clinical roles and to ensure the integration of theoretical knowledge with hands-on experience. This collaborative approach can help inform ongoing research into the suitability and application of preceptorship models for nurses, with the potential for broader application to other healthcare professions.

Recommendations for future research

Further research is needed to assess the effectiveness of preceptorship models within the Aotearoa New Zealand context, particularly regarding their impact on student learning and clinical practice outcomes. Given the evolving nature of healthcare education, longitudinal studies are recommended to evaluate the long-term benefits of preceptorship models and their influence on professional development. Additionally, research should focus on identifying best practices for equipping preceptors with the necessary skills and resources. The Aotearoa New Zealand context is unique due to its bicultural constitution (for Māori and non-Māori) and this influences how preceptor models are constructed, operated and evaluated. The absence of such considerations in this review reflects that articles arose from international research that did not specifically consider indigeneity in preceptor models or stakeholder relationships. A focus on culturally relevant preceptorship models, including their application to diverse student populations, will further enrich the development of effective clinical teaching strategies. Studies exploring the collaborative efforts between academic and clinical institutions in preceptorship will provide valuable insights into optimising student outcomes and ensuring future nurses are prepared for the challenges of modern healthcare environments.

CONCLUSION

Findings from this review suggest that there are various ways to facilitate preceptorship, as the suitability of various models depends on specific circumstances. Factors such as individual staffing levels and personnel dynamics profoundly shape the choice of preceptorship model. Stakeholders with an understanding of the advantages and limitations of each model, can select and implement the most appropriate approach. However, they should remain flexible and ready to adjust strategies as staffing or clinical circumstances evolve. The effectiveness of preceptorship also relies heavily on supporting personnel such as clinical liaisons, coaches, and educators. Further clarity regarding the roles and structures of these positions within dedicated education units (DEUs) could enhance their impact. Ultimately, the overarching objective is to equip student nurses with the skills necessary for safe, independent practice, all while safeguarding against burnout within the nursing workforce. Balancing these priorities is essential for the long-term sustainability of nursing education and practice.

Funding

None

Conflicts of Interests

None