BACKGROUND

Pregnancy brings profound biopsychosocial changes which can increase vulnerability to mental illness during the antenatal period (Ministry of Health, 2012). Changes in reproductive hormones can also increase the risk of mood disorders and mental health symptoms (Friedman et al., 2016) and mental illness is associated with increased maternal and infant mortality and morbidity (Howard & Khalifeh, 2020). Maternal mental illness can also disrupt neurodevelopmental pathways for the baby, resulting in impaired executive functioning (Low et al., 2021). Perinatal mental illness covers a wide range of symptoms and diagnosis, for example, depression, anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorders, trauma and stress, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sleep disorders, suicidal ideation, self-harm, thoughts of harm to the infant, psychosis, and bipolar disorders (Percudani et al., 2022).

Internationally, mental illness is one of the most common comorbidities in pregnancy, with 20% of women reporting mental distress during this time (Bauer et al., 2014). In Aotearoa, 12-18% of mothers’ experience mental distress in the perinatal period (Ministry of Health, 2021) and maternal suicide is currently the leading cause of death in Aotearoa for women during pregnancy and up to six-weeks post-birth (Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee (PMMRC), 2021). Rates of suicide within Aotearoa for women during this period are seven times higher than in the United Kingdom (UK) (PMMRC, 2017) and according to the PMMRC (2021), rates of maternal suicide for wāhine Māori (Māori women) were 3.35 times higher than non-Māori women.

Psychotropic medications are a group of medications that are often the first line treatment for severe mental illness, and can be grouped into the following categories; antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics and mood stabilisers. This range of medications are designed to influence brain chemistry, specifically neurotransmitters with the aim of treating the symptoms of mental illness, by inducing changes in awareness, mood, behaviour, perception or sensation (Agravat, 2024). Psychotropic medications are often a necessary component of treatment (Kulkarni et al., 2015) as the dangers of untreated mental illness can outweigh the risks of medication use (Chisolm & Payne, 2016). However, psychotropic medication use is not without risks. Side effects within the general population include metabolic syndrome, obesity, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, hyponatremia, gastrointestinal conditions, renal diseases, and diabetes mellitus (Correll et al., 2015). Furthermore, when considering the use of psychotropic medications during pregnancy, it should be noted that pregnancy itself presents extra difficulties for medication use, including altered drug metabolism and increased metabolic vulnerabilities (Galbally et al., 2018).

When reviewing current literature, studies show that there is an increased association between antidepressant use in pregnancy and preeclampsia, postpartum haemorrhage, and gestational hypertension (Grzeskowiak et al., 2015; Heller et al., 2017; Palmsten et al., 2013, 2020; Zakiyah et al., 2018). Risks have also been identified in relation to the use of antipsychotics during pregnancy. Studies by Ellfolk et al. (2020) in Findland, Bodén et al. (2012) in Sweden, and Park et al. (2018) in the United States (US) found a marked association between antipsychotic use in pregnancy and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), likely related to the known negative metabolic profiles of these medications, such as impaired glucose metabolism. In a study conducted in Aotearoa, Friedman et al. (2016) found an increased rate of GDM for those taking antipsychotics (13%) compared to the national average (5-9%). Finally, Galbally et al. (2019) conducted a retrospective study in Australia and found that the overall rate of GDM was 17.3% for those taking antipsychotic medications compared to 10.7% for those not taking antipsychotics. Given these identified risks, it is important to understand the prevalence of prescribing rates of psychotropic medication during the antenatal period.

An unpublished literature review by the lead author (CG), undertaken to inform the research presented in this paper, identified 13 studies addressing this question. However, only two of these studies were conducted in Aotearoa and both focused solely on rates of antidepressant prescribing (Donald et al., 2021; Svardal et al., 2021). Donald et al.'s review of dispensing records of antidepressants of 805,990 pregnant women showed an increase in pregnancies exposed to antidepressant medication between 2005 and 2014 from 3.1% to 4.9%. Svardal et al.'s study examined data from interviews of 6822 women in the third trimester of pregnancy as part of the Growing Up in New Zealand longitudinal study and estimated a national prevalence of prescribing antidepressants of 3.2%, with no significant difference in prescribing rates related to age or deprivation quintiles. Lower rates of use of antidepressants were found in younger age groups and lower prevalence of dispensing for Māori, Pasifika, and Asian women compared with European women was also reported (Donald et al., 2021; Svardal et al., 2021). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) were consistently found to be the most common class of antidepressants prescribed in pregnancy across all studies (Alwan et al., 2011; Donald et al., 2021; Ishikawa et al., 2020; Margulis et al., 2013; Svardal et al., 2021).

Overall prevalence of antipsychotic prescribing from 8.4 million pregnancies in 10 countries, ranged from 0.28% in Germany to 4.64% in the UK (Reutfors et al., 2021). Park et al. (2017) conducted a study in the US involving 1,522,247 pregnancies and found a 3-fold increase in atypical (second generation) antipsychotic prescribing between 2001 to 2010. Similar results were found in a study involving 585,615 pregnancies in the US with a 2.5-fold increase for prescribing from 2001 to 2007 (Toh et al., 2013). A further large study conducted in Denmark between 2000 and 2016 found that quetiapine was the most prescribed antipsychotic, comprising of more than 50% of antipsychotic prescriptions (Damkier et al., 2018). They also found an increase in prescribing for mood stabilisers over their study period (Damkier et al., 2018).

The increase in prescribing of antipsychotics may be attributed to several factors such as shifts in diagnostic patterns, a more comprehensive range of indications for antipsychotics and a surge in off-label prescribing (Toh et al., 2013). However, no New Zealand data could be identified regarding antipsychotic prescribing.

The lack of New Zealand specific data is a significant gap, particularly in terms of developing evidence-based prescribing and monitoring guidelines. Indeed, whilst international guidelines highlight the importance of monitoring psychotropic medications during the antenatal period, there is no similar policy or guideline in Aotearoa. Neither are there national metabolic monitoring guidelines to ensure consistency of care (Møller-Olsen et al., 2017; O’Brien & Abraham, 2021). This is worrying due to strong evidence of the association between psychotropic medications and increased risk of adverse physical health outcomes during the antenatal period. Aotearoa-specific research is also needed to meet the obligations of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Māori experience barriers in access to care, leading to poorer health outcomes and life expectancy, among other consequences (Hobbs et al., 2019). Similar patterns are also evident for Pasifika people. Identifying patterns of prescribing for Māori and Pasifika women is therefore important to identify potential inequities and experiences of care and clinical practice. It is important to note that throughout this study, we did not assume a deficit-focused view, but instead concentrated on identifying opportunities to strengthen care for Māori and Pasifika women.

It was within this context that the focus for the current study was to understand the prevalence and patterns of prescribing for psychotropic medications in pregnancy within one maternal mental health service in Aotearoa, and to consider what recommendations may enhance care for those prescribed psychotropic medications during pregnancy.

Study Aim

To identify and understand the prevalence of psychotropic medication prescribing during the antenatal period within an urban maternal mental health service in Aotearoa.

Research Objectives

-

To collate routinely collected date regarding prescribed psychotropic medication for women who utilised a maternal mental health service during pregnancy over a five-year period.

-

To analyse this data to determine the prevalence of psychotropic medication prescriptions and associations with key socio-demographic characteristics.

-

To formulate recommendations to inform service delivery and future research in this area.

METHODS

This single-site study was conducted at Auckland District Health Board (now Te Toka Tumai Auckland, Te Whatu Ora/Health New Zealand). A quantitative, non-experimental, descriptive research design was employed, utilising a longitudinal retrospective approach to gathering and analysing routinely collected data from existing health databases. Data were collected from the medical records of all women who presented to maternal mental health services between January 2016 and January 2021. This information was sourced via Healthcare Community (HCC) mental health database and HealthWare, the maternity and obstetric database utilised by Te Toka Tumai Auckland. Māori mental health services and the Women’s Health and Neonatal Research Governance group were consulted and granted approval for the study. Ethics approval was provided by Auckland Health Research Committee (approval number – AH22715).

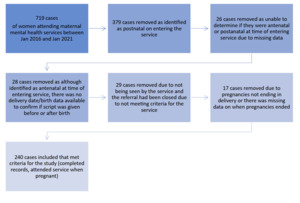

Data were initially retrieved by a coder from Health New Zealand - Te Toka Tumai Auckland using relevant national health index (NHI) numbers. Each case was then de-identified before being sent to the researcher. Information gathered was determined by the nature of the routinely collected data and included age, ethnicity, deprivation, psychiatric diagnosis, estimated delivery date, the actual date of delivery, the type of psychotropic medication prescribed, date of prescribing and the dose. The retrieved ethnicity data had been prioritised hierarchically into six main ethnic groups – Māori, Pacific peoples, Asian, MELAA (Middle Eastern, Latin American, African), Other European, and NZ European. Deprivation, as calculated using the New Zealand Index of Deprivation, was grouped into low deprivation (deciles 1-3), medium deprivation (deciles 4-7), and high deprivation (deciles 8-10) (Egli et al., 2020); and diagnostic data using DSM-4. Between January 2016 and January 2021, 719 women were initially identified as utilising the maternal mental health service. Following the retrospective review of their cases using the process outlined in Figure 1, the data from a total of 240 records of women who were under the care of maternal mental health services during their pregnancy were included in the final sample.

Data was analysed to address the research aims and objectives with support from an experienced biostatistician. First, the prevalence of prescribing was calculated using descriptive analysis. Chi-squared tests of independence were then performed to examine the relationship of prescribing to key socio-demographic variables including ethnicity, area deprivation, and age.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Two thirds of the sample were NZ or other European. Pacific peoples had the lowest representation at 6.3%, despite the Auckland Pacific population being approximately 16% (Auckland Council, 2024) (Table 1).

Of the sample, 26.7% lived in areas of low deprivation (deciles 1-3), 46.3% in areas of medium deprivation (deciles 4-7), and 27.1% in areas of high deprivation (deciles 8-10). Twelve women (5%) were aged ≤ 20 years, 28 (11.7%) aged 21-25 years, 48 (20%) aged 26-30 years, 81 (33.8%) aged 31-35 years, 58 (24.2%) aged 36-40 years, and finally 13 (5.4%) women ≥ 41 years. Depression and anxiety were the most common diagnoses among the sample, affecting 105 (43.8%) and 79 (32.9%) women respectively (Table 2).

Whilst there was no association between diagnosis, ethnicity or age, there was a statistically significant association between diagnosis and levels of deprivation (Table 3), with women diagnosed with psychosis-type disorders being more likely to live in areas of high-level deprivation (deciles 8-10); Chi-square test X2 (Chi-square test) (df = 10, N = 240) = 24.851, p = 0.0060.

Prevalence of medications prescribed

From the cohort of 240 women, 156 (65%) women were prescribed psychotropic medication during pregnancy. Of the 156 women prescribed medication, 121 (77.6%) were prescribed an antidepressant, 72 (46.2%) were prescribed an antipsychotic, 27 (17.3%) had an anxiolytic included in their prescription and 6 (3.8%) were prescribed a mood stabiliser.

The most prescribed medications were, sertraline 48 (30.8%), quetiapine 47 (30.1%), and escitalopram 29 (18.6%). In total all other specific medications prescribed were below 9%. Interestingly, overall, a high rate of antipsychotics was prescribed (46.2%); however, diagnosis rates for psychosis-type disorders were low (4.6%), indicating possible off-label prescribing.

Ethnicity and prescribing of psychotropic medications

Rates of prescribing psychotropic medications across the ethnicities ranged from 60.2% for NZ European women, with highest rates for Pasifika peoples (n=11, 73.3%) and other European women (n=28, 73.7%) (Table 4).

A chi-square test showed no statistical significance between ethnicity and the prevalence of prescribing: X2 (df = 5, N = 240) = 2.797, p = 0.731. There was also no association found between the type of psychotropic medication prescribed and ethnicity, area deprivation, or age. However, it was interesting to note that our results showed that Māori had the highest rate of antipsychotic prescribing, with (n=13) 36% receiving a prescription, as compared with (n=28) 29.6% of NZ European women.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first in Aotearoa New Zealand to explore the prevalence of prescribing all psychotropic medications in the antenatal period within a specialist maternal mental health service. We found that 65% of women, in the total cohort of 240 pregnant women, were prescribed psychotropic medications during their pregnancy. Whilst not necessarily surprising, as specialist maternal mental health services are at the sharp end of the spectrum of care, this study provides the first data nationally regarding the prevalence of prescribing for all psychotropic medications in pregnancy within a specialist service. Furthermore, given the known associations between psychotropic medications and comorbid physical health issues, these results have important implications for enhanced practice.

We found that those living in areas of high-level deprivation had statistically higher diagnosis rates for psychosis-related disorders (63.6%) compared to women living in areas of low-level deprivation (9.1%). These findings are in line with evidence that maternal mental distress increases in line with levels of socioeconomic deprivation (Katz et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2014). However, more research in this area would be beneficial, particularly around the experiences of women receiving care. Because psychosis-related disorders in pregnancy and the postpartum period should be managed as psychiatric emergencies (Tinkelman et al., 2017), ensuring access to mental health care for those living in areas of high-level deprivation is important. Given these findings, there is a strong argument for establishing a more integrated model of care.

Over three quarters of the 156 women that received a prescription for a psychotropic medication were prescribed an antidepressant, with the SSRI antidepressants sertraline and escitalopram being two of the most prescribed medications. This finding is consistent with previous research showing that antidepressants, in particular SSRIs, are the most prescribed psychotropic medication in the antenatal period both internationally and within Aotearoa New Zealand (Alwan et al., 2011; Donald et al., 2021; Ishikawa et al., 2020; Margulis et al., 2013; Svardal et al., 2021).

Seventy-two (46.2%) of those prescribed medications were prescribed an antipsychotic despite just 4.6% having a documented psychosis-type disorder. Wāhine Māori were the most common group by ethnicity to have been prescribed antipsychotics, with 36% receiving a prescription in our cohort. This finding is in line with the conclusions of an Aotearoa New Zealand study conducted between 2008 and 2015 on antipsychotic prescribing in the general population, which found prescribing rates for Māori were the highest, compared to all other recorded ethnicities (Wilkinson & Mulder, 2018). Further research is needed to explore this finding.

Given the increased risk of association between antidepressant use in pregnancy and comorbid physical health conditions such as gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and postpartum haemorrhage (Grzeskowiak et al., 2015; Palmsten et al., 2020; Zakiyah et al., 2018), as well as the increased risk for gestational diabetes with the use of antipsychotic medications (Bodén et al., 2012; Ellfolk et al., 2020; Friedman et al., 2016; Galbally et al., 2019; Park et al., 2018) it is important to consider enhanced communication between mental health, maternity service and primary care providers on this topic.

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists recommend that perinatal mental health care be integrated into maternity care during the antenatal period, with enhanced communication and collaboration between mental health services and maternity services, as this will assist in avoiding challenging clinical scenarios (Galletly et al., 2005; The Royal Australian & New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 2021). This supports our recommendation for establishing an integrated model of care and the value of creating a role for perinatal mental health nurse specialists within maternity and obstetric services.

Models of service delivery that prioritise early intervention, prevention, and promotion while promoting better referral channels between primary care and specialised mental health services are essential for better perinatal mental health (Harvey et al., 2011). Harvey et al., discuss one such model of care in Australia that was created in response to the National Perinatal Depression Initiative, which is a nurse-led, consultative liaison, primary care-focused approach to perinatal mental health assessment and brief intervention. While preserving clinical efficacy, this provides primary health professionals with a more flexible and accessible service model (Harvey et al., 2011).

Perinatal mental health nurse specialists possess the skills and knowledge to have greater involvement because they have knowledge and understanding of perinatal mental health symptoms and disorders, as well as physical health issues, pregnancy and pharmacology (Allison, 2004). Such nurses could provide improved access to specialist mental health services through timely mental health assessments, including for those who face significant socioeconomic disadvantage, health disparities and stigmatisation (Ministry of Health, 2012). Emerging evidence is showing the value of enhancing midwives’ and primary healthcare nurses’ knowledge in this space to promote the mental of health of pregnant women (Karalia et al., 2024; Noonan et al., 2019). Strong collaboration and communication between all service providers will lead to improved access and care for women.

As noted previously, our study results showed that 72 (46.2%) of those prescribed medications were prescribed an antipsychotic medication, however only 11 (4.6%) of the total cohort had a documented diagnosis of a psychosis-type disorder. This may be an indication of off-label prescribing; however, this cannot be determined conclusively from the data collected. Our results also revealed that the antipsychotic medication quetiapine was a commonly prescribed first and second-line medication, with a total prescribing rate of 30.1% of the 156 women prescribed psychotropic medications in pregnancy. Our results are similar to international studies showing quetiapine is the most common atypical antipsychotic used during pregnancy (Betcher et al., 2019; Damkier et al., 2018; Huybrechts et al., 2016; Johnson et al., 2016). Within Aotearoa New Zealand, our findings align with Friedman et al.'s (2016) study, which was conducted at the same maternal mental health service. Quetiapine has been approved in Aotearoa New Zealand to treat only schizophrenia, acute mania associated with bipolar I disorder (Huthwaite et al., 2018). Our results for those being prescribed quetiapine appear to be high, therefore these findings may indicate possible off-label prescribing, however again this could not be determined by the data collected. Quetiapine is known to cause weight gain and other metabolic issues, although the underlying mechanisms are complex and poorly understood, with limited data on how dosage affects metabolic disturbances (Dubath et al., 2021). Thus, the increase in off-label low-dose quetiapine prescriptions (such as 150mg/day) is cause for concern (Dubath et al., 2021).

Therefore, there is a need to ensure caution is taken when prescribing low-dose quetiapine in pregnancy (Friedman et al., 2016; Møller-Olsen et al., 2017). It would be beneficial for maternal mental health services to collect data related to off-label prescribing with regards to all antipsychotic medications. Additionally, a clear metabolic monitoring policy that identifies who is responsible for monitoring metabolic side effects of antipsychotics in pregnancy is also required. Again, this supports a need for enhanced communication between maternal mental health services, obstetric services, midwives and primary healthcare clinicians with clear monitoring guidelines to ensure women receive the best care possible. Perinatal mental health nurse specialists may be invaluable in this space to coordinate and provide specialist care and support the woman to navigate through the various services. However, further research is also required to identify best practice from the perspectives of women who experience mental health problems during pregnancy.

Table 5 provides the recommendations for nursing practice, policy, and research.

Strengths and limitations

This retrospective study was reliant on routinely collected data. There was some missing data due to inconsistent recording of clinical information at the time of presentation to clinical services. Furthermore, available data could not indicate whether prescribing was due to pre-existing symptoms or new symptoms. Data was collected over the period of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, no information was available regarding the impact of the pandemic on prescribing patterns. For pragmatic reasons data collection focused on one specialist maternal mental health service within a large population district health board only. However, this study does have several strengths; for instance, it is a first step in looking at prescribing practices for psychotropic medication at Te Toka Tumai Auckland since the intention to monitor prescribing practices was outlined in the previous strategy (Auckland District Health Board, 2019). To our knowledge, this study was the first to examine all psychotropic prescribing within a specialist maternal mental health service. It is also the first study in Aotearoa New Zealand to look at the prevalence of a full range of psychotropic medications in the antenatal period. Findings are in line with national and international research where this exists indicating data accuracy.

CONCLUSION

Maternal mental health is an essential area of public health and providing the best care for pregnant women with mental illness presents a unique challenge to clinicians (Niethe & Whitfield, 2018). Of 240 women receiving care during pregnancy from an urban maternal mental health service within Aotearoa New Zealand, most (65%) in the study and were prescribed psychotropic medications. These findings support the need for early physical health screening, closer monitoring, and enhanced communication between mental health specialist clinicians and health professionals involved in the general care through a woman’s pregnancy. We also recommend the creation of policy and guidelines for managing psychotropic medications in pregnancy for Aotearoa New Zealand, as well as integrated health models to enhance holistic care for women during this time, which are culturally safe and promote health equity. We suggest further research is necessary in this area, as well as local and national training for nurses, nurse practitioners, midwives, obstetric staff and other clinicians working in perinatal mental health care.