INTRODUCTION

In 2023 the first programme to support newly registered nurse practitioners (NPs) transitioning into primary healthcare (PHC) settings was launched in Aotearoa New Zealand and was funded by Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora for two years. The transition programme arose from ongoing work as part of a nationally-funded Enrolled Nurse and NP Workforce Programme, led by the University of Auckland and in collaboration with partners from PHC, universities delivering the national Nurse Practitioner Training Programme (NPTP), and Nurse Practitioners New Zealand (NPNZ). The funding available from Health New Zealand was specifically for NPs working in PHC and community settings, with a contractual expectation that NPs would promote access to primary mental health and addiction services. The purpose of the transition programme was to support newly registered NPs, within their employing organisations, to better integrate into their practice settings, have time to orientate to their new scope of practice as a NP, and to deliver services that would meet the needs of their local communities. This included a focus on improving healthcare access to advance equity, including for mental health and addiction services. The transition programme supported 32 NPs in 2023 and 43 in 2024. There was no funding for this Programme in 2025.

In May 2025, Health New Zealand sent out a request for proposal (RFP) to the health and tertiary education sector for a new “Nurse Practitioner Training Support Scheme” (Health New Zealand, 2025) launched through the Government Electronic Tenders Service (GETS) as a competitive tender process. The lack of inclusion of NPs in the policy direction and funding of NP education and training has been discussed elsewhere (Adams et al., 2024). The Scheme will replace the national NPTP, instead providing a support package for 180 NP candidates (120 in PHC; 23 in mental health and addiction settings) and their organisations, which includes preparation for and during the final practicum year and through the first six months as a newly registered NP, and supporting registered nurses on their pathway, prioritising Māori, Pacific, and those working in mental health and addiction services. In this paper, we present the evaluation of the pilot transition programme and learnings for establishing a sustainable funded model in Aotearoa New Zealand.

BACKGROUND

Across the globe, NPs are transforming PHC service delivery, providing cost-effective models of care that promote health within communities as well as providing comprehensive primary care services with similar or improved health outcomes to general practitioners (Barnett et al., 2022; Laurant et al., 2018; Turi et al., 2023). Increasingly, the NP role is being recognised for its potential to deliver services to underserved, rural and Indigenous communities (Adams, Komene, et al., 2024; Porat-Dahlerbruch et al., 2022; Rosa et al., 2020). NPs are meeting gaps in an era where there is a shortage of general practitioners (GPs), increased demand on urgent care and emergency departments, increased prevalence of complex co-morbidity and mental health and substance abuse issues, and an increasing desire to offer healthcare that addresses health equity (Adams & Carryer, 2023; James-Scotter et al., 2025; Mohan et al., 2024; Mustafa et al., 2021). It is imperative that this valuable and economically viable NP workforce is enabled, well cared for, and protected to optimise their ongoing contribution to the health of New Zealanders.

In June 2025, 910 NPs were registered with the Nursing Council of New Zealand (the Nursing Council) (2025); an increase of 300 in the past three years, primarily as a result of increased training places through NPTP. In Aotearoa New Zealand, NP candidates are master’s degree prepared experienced registered nurses (RNs) (Nursing Council of New Zealand, n.d.-a). The final NP year of education and clinical training prepares NP candidates for a change in scope of practice and role, undertaken within a clinical practicum. Candidates are mentored by a NP from the tertiary education institute and work alongside a clinical supervisor, who is an authorised prescriber (either a NP or GP) within a particular clinical setting. On successful completion of the 10-month programme, the NP candidate prepares a portfolio demonstrating their competence in the NP scope of practice and applies to the Nursing Council to be registered as a NP (New Zealand Government, 2017; Nursing Council of New Zealand, n.d.-b). Their submitted application and portfolio are assessed by a panel of expert NPs, on behalf of the Nursing Council. The panel makes their recommendation to the Registrar at the Nursing Council. Once registered as a NP, the novice NP may immediately begin work within the NP scope of practice. From this point on, the NP is able to work autonomously as a lead care provider to assess, order a range of laboratory investigations, diagnose, and prescribe medications and treatments (as an authorised prescriber), and refer to specialists.

Nurse practitioner role transition describes the transition period from working as a RN, through their NP candidacy, as a novice NP in the new scope of practice through to being an autonomous and confident NP (Whitehead et al., 2022). The transition period is recognised as a time of considerable personal and professional growth where NPs are building on the foundations of their education and training (Johnson & Harrison, 2022). Globally, NPs experience role ambiguity, reality shock, and a struggle for legitimacy, experiencing mixed emotions of feeling anxious and overwhelmed, together with excitement at the possibilities of a new role and professional identity (Faraz Covelli & Barnes, 2023; Hande & Jackson, 2024; Johnson & Harrison, 2022; Owens, 2019). International evidence identifies the need to support NPs’ transition through their first year of practice and thrive in their new positions (Faraz Covelli & Barnes, 2023; Kaplan et al., 2023; Whitehead et al., 2022).

Successful integration of new NPs during their first year of practice requires, for example, ongoing mentorship and peer support (Barnes et al., 2022; Speight et al., 2019; Whitehead et al., 2022); job description clarity, onboarding and orientation (Faraz, 2019); the development of collegial relationships with other professionals within the team and externally (Burgess & Purkis, 2010; Speight et al., 2019); close support from a senior clinician (Chouinard et al., 2017; Whitehead et al., 2022); organisational support to access required resources to function in the new role (Black et al., 2020); opportunity to develop models of care that give meaning to the NP’s work and shape the service they provide (Adams, Komene, et al., 2024; Contandriopoulos et al., 2015; Porat-Dahlerbruch et al., 2022); professional development (Speight et al., 2019; Tudhope, 2025); and job satisfaction (including autonomy) (Brault et al., 2014; Burgess et al., 2011; Chulach & Gagnon, 2016). Barriers to novice NPs’ transition include a lack of organisational and clinical support, understanding and respect for the NP role, role ambiguity, unrealistic workload with inadequate time to complete tasks, and the complexity of patients (Faraz, 2019; Whitehead et al., 2022). As a result, the United States has seen a rapid growth in programmes to support the first year of transition (2000 hours), known as fellowship or residency programmes, which result in NPs having higher retention rates, being more productive, and having more confidence (Hawes, 2024; Tudhope, 2025). Such programmes are particularly important in PHC and rural settings to reduce burnout and improve retention (Kaplan et al., 2023; Mounayar & Cox, 2021).

DESIGN OF PILOT TRANSITION PROGRAMME FOR NURSE PRACTITIONERS

Transition programme design

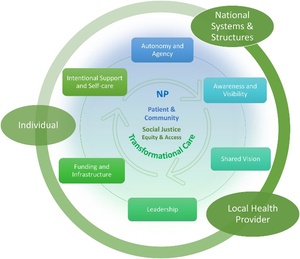

The design of the transition programme grew from international evidence (cited above), together with our evidence synthesis on the integration of NPs into PHC (Adams, Komene, et al., 2024) (Figure 1) and early research findings from our longitudinal research programme on the transition of NPs into practice. This latter research (analysis in progress; Auckland Human Research Ethics Committee, ref. 21900) revealed through qualitative interviews with NPs between six- and 10-months post NP registration in 2022, the lack of support and orientation to their new role. Participants described how, in most part, they were immediately rostered onto a full clinical load, with 15-minute appointments in general practices and expected to work to the same capacity as their senior experienced general practitioner or NP colleagues. They had little or no administration time, no time within their organisation to describe their work, plan their schedule, and receive peer support. They described a feeling of confusion by being a part of the nursing team yet were expected to undertake medical tasks and work as substitute doctors. They experienced stress and frustration at not being able to enact the NP services they had anticipated as NP candidates (Adams et al., 2025).

The design of the transition programme was led by the co-leaders of the EN/NP Workforce Programme (SA, JD) in collaboration with NPNZ, and with support of the governance group. The governance group included a wide range of nurse leaders, NPs, and heads of schools and operated under a Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Treaty of Waitangi) framework, to ensure principles of Te Tiriti were enacted, including tino rangatiratanga (self-determination), equity, and partnership (Public Health Advisory Committee, 2023). A proposal was submitted to Health New Zealand to fund the pilot transition programme from existing funding within the EN/NP Workforce Programme. The service objectives included support for 18 NP positions in PHC to improve healthcare access and particularly provide primary mental health and addiction (MH&A) care. Thirteen NPs participated in these establishment positions and then through the transition programme we extended the reach to a further 75 NPs in 2023 and 2024.

Application process

The transition programme was approved by Health New Zealand and launched in November 2022 for a first cohort to start in February 2023. Eligible applicants were expected to be completing their NP training and expecting to apply for NP scope of practice (with the Nursing Council) within the following three to six months. Applicants were included (and represented in the programme) from all nine NP tertiary education training providers in the country; and who were working in PHC or community settings, including aged residential care. The programme was also open to specialist mental health NPs working in the community. Information on the programme was disseminated through NP course directors and academic mentors, Health New Zealand media, and professional groups. All those meeting the criteria were invited to join the programme.

A central application process required the employer (leader or manager) to complete an expression of interest with the NP candidate and was jointly signed. The expression of interest included a commitment to employ the NP candidate on registration as a NP and descriptive information under the following three areas: 1) achieving health equity under the obligations of Te Tiriti o Waitangi; 2) improving healthcare access for marginalised and underserved populations and communities, and particularly increasing access to MH&A care and services; and 3) developing a model of NP care that optimises the scope of NP practice to promote hauora (health and wellbeing). Co-leaders of the programme held discussions with employers and NP candidates as required. A letter of agreement was formally signed and funding released when the applicant had successfully registered with the Nursing Council as a NP. Given the staggered timings for registration as a NP, all applicants commenced the programme and attended the first workshop in mid-February, regardless of their NP status. Approximately 80% of programme participants were registered as NPs by mid-February.

Of the 75 programme participants, approximately one third worked in rural or semi-rural settings. Sixteen were employed by Health New Zealand and of these 11 worked in community mental health and addiction NP roles. The participating NPs were geographically spread across the country, representing 18 of the 20 Health New Zealand districts. Ethnicity and clinical practice settings of the participants are shown in Table 1. There were no Pacific participants.

Programme intent and outline

The purpose of the transition programme was to provide a supportive environment for newly registered NPs working in PHC and community settings to promote their successful integration into practice; and by so doing, promote job satisfaction and retention and reduce burnout and stress. The main components of the programme were:

-

Provide funding to the employing organisation to enable an orientation period, longer appointments, and access to clinical peer support.

-

Provide professional development funding for non Health New Zealand employed NPs at a rate equivalent to that received by NPs employed through Health New Zealand.

-

Deliver five workshops across a 10-month period to facilitate ongoing collegial connection, support self-care, learn from more experienced NPs, and encourage the participants to realise their aspirations for NP service delivery, particularly to promote health equity.

-

Deliver a mental health and addiction online short course.

-

Facilitate new NPs to receive mentoring from a NP and professional supervision.

The co-leads of the programme were available to practices and NPs to provide advice and trouble-shoot as required on issues relating to integration into practice, service delivery models, and pay and conditions. Alongside the transition programme, NPNZ established a two-day professional mentorship course to build the capacity, capability and national consistency of mentoring NP candidates.

The transition programme was structured over three time periods (Table 2). The programme funded the NP salary contribution at $60.00 in 2023 and $62.50 in 2024. While many NP participants considered this to be low and were receiving a higher salary, we knew there were many providers who were unable to fund a NP at a higher salary rate. NPNZ (2024) have since released a remuneration guideline for NPs in PHC.

The workshops were facilitated by SA and JD, with support from EK and guided (more so in 2024) by the NP integration framework (Figure 1) to identify areas of strength and challenges to NPs successfully transitioning into practice. Workshops also included guest speakers (mostly NPs) and time given to the participants in breakout groups for reflection. Topics from guest speakers included NP transition experience; self-care; professional indemnity; professional supervision and NP mentoring; contracting and negotiating employment; and ways of working, service delivery models and innovative models of care.

The MH&A short course was developed and led by two NPs (JD, SB). The course was underpinned by Te Tiriti o Waitangi and designed specifically to support the growth and confidence of NPs working in PHC and community settings delivering services for people experiencing mental health and/or addiction concerns. Five two-hour online sessions were delivered as five distinct modules - baseline knowledge, mood disorders, anxiety, psychosis and substance abuse - focusing on the most common PHC/community MH&A presentations and with an emphasis on aetiology, diagnostic criteria and screening tools, and treatment options, which included pharmacotherapy, de-prescribing, and non-pharmacological interventions. The sessions were highly interactive with NPs expected to share cases and undertake short post-module learning exercises, making the learning meaningful to practice. The course was not formally evaluated and is now being run through NPNZ.

PROGRAMME EVALUATION

Our descriptive evaluation reported sits under the umbrella of a wider longitudinal research programme exploring the transition of NPs into practice, including educational preparation and organisational support, through online annual surveys and interviews. Ethics was approved by the Auckland Regional Human Ethics Committee (ref. AH24954). We report here only on the evaluation of the pilot transition programme, specifically: 1) the perceived value of the programme and its components; 2) the extent to which the programme’s requirements were met by participating NPs and organisations; 3) the value of the workshops as a delivery model; and 4) whether NPs’ aspirations to deliver healthcare services had been met during the first year of practice. The survey items were drawn directly from the components of the programme with responses on a three- or four-point Likert scale. Participants were asked to rate each item and provide comments. The survey items together with the response options are shown in the findings in Figures 2 to 5.

The evaluation of the transition programme took place during the final workshop of the year. Sixty-two NPs attending the workshops (November 2023 and 2024) were invited to respond to an online Qualtrics survey. They were provided with a participant information sheet and survey link. The first page of the survey included the consent form, with a forced (Yes/No) response question. Only by consenting to participate in the study could the NPs progress to the survey questions. Some completed the survey during this time, while others responded at a later time. Those not attending the workshop were emailed and invited to participate in the survey.

Survey item responses ranged from 40 to 55 per item of a possible 75 participants (53% to 73% response rate). Quantitative data was analysed descriptively (CB) with the mode number of responses given for each set of topics (Figures 2-5). A total of 258 free text comments were recorded from 64 participants. Open comments were entered into an excel sheet and then grouped in relation to survey questions (SA, EK). We have presented a range of comments to show the breadth of experience of the transition programme and particularly to highlight learnings for future programmes, including for the Health New Zealand funded programme commencing in 2026.

FINDINGS

The importance of a transition programme for newly registered NPs

Across the descriptive quantitative data and comments from the NP participants, there was overwhelming agreement of the need for a transition programme for newly registered NPs. Participants were asked to rate how important various components of the programme were to their first year of practice (Figure 2). The top four items deemed “essential” by 80% or more of participants were professional development funding; funding to support the organisation to employ a NP; funding to enable an orientation period; and funding to reduce clinical load (such as longer appointment times). Opportunities to develop innovative models of care and having time to engage with local communities and social service providers was considered least essential, though 95% considered that supporting their intentions to work holistically was important or essential. Just a very small percentage of participants rated some components not important. In relation to funding components, this could be that the NP was employed in an organisation where the necessary support was already in place.

Qualitative comments affirmed the value of the transition programme and the necessity for funding:

The funding from the transition programme was SO helpful in general practice. It guaranteed my access to peer support, professional development, and longer appointment times. [P7, 2023]

The transition programme provided “a framework that ensured support was in place” [P8, 2024]. Other NPs described how it allowed them to “transition well into my role” [P9, 2024] and to “have a safe space and time to grow as a novice NP, for which I am very grateful” [P15, 2023]. They also highlighted the opportunities the transition programme gave them to support their advanced practice:

The NP transition programme and study days helped create a shared vision to keep new NPs practicing as we were able to share experiences, network, and feel validated in our vision of delivering advanced nursing care. [P13, 2024]

[The] NP transition programme supported new NPs to develop confidence as they developed autonomy to deliver NP advanced nursing practice. [P13, 2024]

Emerging through these comments was how a formalised transition programme highlighted to organisations and other clinicians the necessity of supporting newly registered NPs to transition to a new scope of practice:

I think it was a really helpful transition. With my colleagues being aware that I was involved with the transition programme gave an understanding of the time needed to move into this scope of practice. I hope that those coming through are offered the same opportunities as I have had to support practice in the future. [P3, 2024]

Meeting the transition programme’s requirements

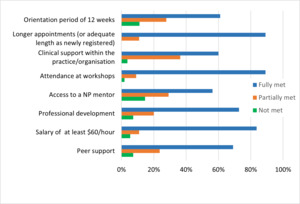

The NP participants were asked to rate and comment on the extent to which the requirements of the transition programme had been met within their organisation (Figure 3). Despite the transition programme contributing to 40% of the salary for the first 12 weeks of the orientation into practice, only 61% (n=54) described this as being fully met. However, 89% did have longer appointment times. The salary of nine NPs (seven in 2023 and two in 2024) did not meet or only partially met the requirement $60/hour. One NP commented that this was because it took several months to negotiate a salary of over $60/hour. Only 56% of new NPs had access to a NP mentor.

A small minority of NPs and their organisations struggled with delivering the programme requirements, due to various factors, including “staff shortages” [P12, 2023], “time constraints” [P16, 2023; P17, 2024], a lack of “clear understanding” [P13, 2023] of the programme itself, and organisations understanding the NP role and need for supporting novice NPs. Despite funding the employing organisations, some NPs reported a lack of access to the funding, and several had no or limited orientation:

There needs to be more control of the funding - it was given to my employers and then I battled with my employers for access to the funding for PD [professional development] and professional supervision. I don’t know how to fix that, but I wish none of the funding had gone to Te Whatu Ora, because I haven’t used any of it. [P8, 2023]

I had no orientation at either practice - at my new practice, I was working on my own the first 2 days due to GP [general practitioner] illness.[P16, 2023]

The majority of NPs clearly had the requirements of the programme met within their organisations and commented on the support given to them:

30-minute appointments until December 2023 (the whole year). I used the funding for the GPCME [general practitioner continuing medical education], which was funded, and attended the workshops for which I was paid. I have had my first pay raise already. [P4, 2023]

I have an extremely supportive team and management who value me and the role of NP. I have been supported to continue having 30-minute appointments. [P5, 2023]

I have been really well supported by my practice manager to grow my role. [P16, 2023]

Not surprisingly, others had less positive experiences highlighted, in the main, by a lack of understanding of the role of the NP:

My employer was not quite prepared for the NP scope of practice. It took quite some time to clearly identify my role. As an advanced practitioner, I continued to be used as a ‘gap filler’ around the organisation without appropriate pay or conditions. It was difficult to manage. Essentially, I was used to cover a range of general nursing vacancies. I had to advocate strongly for myself for this to stop and for my own role to be valued in practice and via pay and conditions. Still a work in progress. [P6, 2024]

My organisation are still working out how to best use my skills. [P19, 2024]

Several NPs fed back on the value of the support from the programme’s leaders in helping them establish NP services in their clinical setting. This included discussions with the leaders of the services. However, despite these efforts, seven NPs changed employers during their first year:

The support from [programme leaders] has been integral to my ability to move to a Māori health provider and to actually work in a holistic model, with equity and access at the core of my work. [P18, 2023]

I have spent the year trying to find a practice that would support and pay a nurse practitioner adequately. I feel I have finally landed somewhere in a VLCA [very low-cost access] clinic that is supportive, but this has only been a recent change … it’s been a stressful, unsettling year. [P23, 2024]

I was not gaining traction with my previous employer when I first commenced the NP transition programme, with the goals I had around improving services. They wanted me to stay in the status quo, so I ended up changing employers. [P25, 2024]

The salary of NPs remains a bone of contention with great discrepancies across the country and between sectors and providers. The $60/hour minimum rate was considered by one NP as “grossly out of touch” [P23, 2024] with NP salary rates. However, even at this low rate, several NPs struggled to achieve this salary:

In my previous workplace, I struggled to get clinical support and a salary of $60/hour. In my new role, and with the support of the [programme leaders], I have been able to meet the requirements of the programme. [P18, 2023]

While some NPs did not have time limits for consultations, those in general practice settings highly valued the longer appointments:

The 30-minute and then 20-minute appointments were gold! I kept saying, nothing takes me a standard time, to interpret results can take me an hour!! Things get quicker the more you see, but early on, it is a minefield and decision fatigue is Real! [P12, 2023]

Funding was very helpful in the primary care setting, where they are unwilling to allow time to do longer appointments and learn, as it is all about profits. [P20, 2024]

30-minute appointments have been great, I continue to have these. I put funding towards patients who needed ongoing reviews and who would not be able to afford these visits. [P13, 2023]

Accessing clinical support in the practice setting was not or only partially met for 40% of NP participants:

Clinical support in practice has been difficult to access due to time constraints. I have been fortunate to work 4 days, which has been helpful, and the peer support and connection via the workshops have been helpful. I do worry about burnout, and I think more regular time-outs to catch up with other NPs would be helpful. [P16, 2023]

Again, the transition programme was found useful by NPs to help their employers realise the importance of clinical support and provide support accordingly:

Clinical support is available [for me] in an ad hoc manner. The TP [transition programme] has helped to identify that clinical support within the workplace is essential, especially in the first year, not just for the initial few months. [P22, 2024]

I am seeing increasing patient complexities as I grow in the profession. The NP transition programme has definitely helped to boost my clinical acumen as I got to learn intensively from my GP mentor using available resources from the transition programme. [P4, 2024]

The transition programme encouraged NPs and practices to use the professional development funding flexibly to meet the needs of the individual NP for mentoring, cultural and/or professional supervision. However, those not working with a NP in their practice were encouraged to access a NP mentor externally. Yet 22 NPs (44%) found this difficult, despite the involvement of NPNZ to support finding NP mentors and the funding available:

I did not get NP mentoring/professional supervision until October. I was meant to use the in-house supervisor, who is a GP, but I refused as I did not feel this was appropriate. I have since engaged with an NP who does professional supervision - way more appropriate and helpful. [P31, 2024]

The value of peer support, self-care, and connecting with NP colleagues was highlighted in the survey responses of the usefulness of the workshops (Figure 4). Having time out from everyday work for reflection and connecting with peers were rated by over 90% of participants as very or fairly useful:

I feel peer support was invaluable, and without the transition programme support, I believe I would not have been supported through the year. [P13, 2024]

It has been good to know there is a programme that facilitates the NP network, as well as funding for building our models of care/community. [P6, 2023]

Attending these group sessions allowed me to learn from others and understand that we are going through similar things. [P20, 2024]

Nurse practitioners’ hopes and aspirations

On applying to the transition programme (12 months prior to the evaluation), NP candidates were asked to describe how they intended to deliver healthcare services to meet the needs of their local communities. The descriptions provided by the applicants were innovative and inspirational and strongly described improving access to healthcare and advancing health equity. In the evaluation, NPs were asked about their first year of practice and whether they had been able to meet their expectations for service delivery (Figure 5).

Under 50% responded that they were able to deliver services which met their hopes and aspirations for NP practice, though the majority did feel they were delivering services which both met a gap in health need and advanced health equity. One NP commented how the transition programme enabled their “hopes and aspirations” by being able to:

Build relationships with external providers, … maintain a holistic model in practice, … [and] support me to implement and build a relationship with the community. [P6, 2023]

Another said:

I can definitely see my aspirations and hopes being successful over time. I think over a year (which has gone so fast), it is just the beginning, and my hopes and aspirations have grown; I just need to be patient. Rome wasn’t built in a day, sort of thing!! [P15, 2023]

The opportunities that came with the transition programme, including the workshops, professional development and down-time from clinical appointments, enabled NPs to develop and expand their services to address community health needs and equity:

I have spent a lot of my PD [professional development] time working in areas that would allow further equity - I have upskilled to cover woman’s health and sexual health as we have no other providers in our rural area. I also upskilled in paediatric care to allow my practice [work] to broaden to provide care across the lifespan. [P12, 2023]

Having the transition programme coordinators support me, validated my desire to work in a holistic manner, prioritising equity and improved access. [This] helped me challenge my workplace and to develop and articulate my vision. [P18, 2023]

Several spoke of their desire to have more professional development provided and specifically related to clinical skills; though this was beyond the scope of the programme.

I found the short course [MH&A course] the most helpful (guaranteed PD [professional development] and really useful information), and the connection with my peers was the best. I would want MORE PD - maybe even one session per workshop. [P8, 2023]

One NP summed up the value of the transition programme to the NP as well as their practice and community:

[The] NP transition enabled me to become confident in my new role as an NP by providing time and support to explore and develop myself and my skills as a first-year NP. It enabled me to work within the practice to provide an NP option for patients and families. I was further able to provide acute walk-in clinics improving access and equity, while freeing up GPs to see their more complex patients. [P14, 2024].

DISCUSSION

This paper presents the implementation and evaluation of a transition programme pilot supporting 75 newly registered NPs and their employing organisations in PHC and community settings. Feedback, through surveys and interviews, was overwhelmingly positive and aligns with international literature highlighting the benefits of a 12-month programme in enhancing NP competency and confidence, readiness for practice, retention, and patient outcomes (Lloy et al., 2023; Speight et al., 2019; Tudhope, 2025). The necessary core components required to ensure NPs successfully transition and integrate into PHC settings (Adams, Komene, et al., 2024; Whitehead et al., 2022) were affirmed through the delivery and evaluation of the transition programme.

Critically, NPs need ongoing education and training, meaningful to their context, with both adequate clinical support and support that facilitates their newly emerging role identity (Chouinard et al., 2017; Owens, 2019, 2021; Speight et al., 2019). The support offered through the transition programme pilot was highly valued by newly registered NPs across various dimensions. However, in many ways was a drop in the ocean compared to extensive year-long competency-based programmes delivered in the United States (Tudhope, 2025), which recognise the value of NPs in the health workforce. The funding available to organisations for the pilot programme was small, approximately $29,000 for a NP working fulltime, yet considered essential by over 80% of participants. If Health New Zealand are serious about fully utilising, respecting, and caring for the NP workforce, then growing and expanding the transition programme is essential.

Evident through the first year of practice, in the main, was a lack of access to professional development opportunities, including for clinical skills. The MH&A short course was the first NP-specific post-registration course launched in the country. The course was designed to support implementing best practice care for their communities, particularly those presenting with complex health needs, often compounded by both physical and mental health concerns. Ensuring NPs are adequately equipped to meet the growing demands on PHC services is critical where access to specialist MH&A services has reduced (Ministry of Health, 2024; Te Hiringa Mahara New Zealand Mental Health and Wellbeing Commission, 2024). Recognising NPs as a distinct profession who bridge biomedical knowledge within a nursing paradigm and deliver culturally safe holistic care requires NP-specific short courses.

Our evaluation confirmed the necessity of supporting NP education and professional development in the first year of NP registration to strengthen professional identity, clinical skills, and achieving proficiency (Johnson & Harrison, 2022; Owens, 2019; Whitehead et al., 2022). By 2026, there will be over 1,000 NPs in Aotearoa New Zealand. Yet we are in a time where right-wing neoliberal policies are set on devaluing nursing, eroding professional standards, reducing training hours, and focusing attention away from equity and Te Tiriti o Waitangi principles (Adams, McKelvie, et al., 2024; Loring et al., 2024). There is increasing governmental and health sector pressure to reduce costs to training and education, evidenced by the Regulatory Standards Bill (2025) and the recent RFP for the Nurse Practitioner Training Support Scheme. While details of this new Scheme have yet to be released publicly, Health New Zealand’s expectation is to increase training places for NPs in PHC, support registered nurses before and during the final practicum year, particularly Māori and Pacific nurses, and support newly registered NPs through their transition into practice. At the same time, Nursing Council are proposing changes to NP educational standards, including changing supervised in-practice clinical training hours from 500 to 400 hours per year, with 100 hours of simulation (Nursing Council of New Zealand, n.d.-c). Overall, we anticipate funding to be inadequate to enable the application of the many factors necessary for comprehensive integration and success. It is critical that the NP profession have a strong collective voice to influence policy, regulation, and educational standards to ensure newly registered NPs are well supported and integrated into practice, realising their potential to deliver equity-driven and comprehensive primary healthcare.

Limitations

The paper adds to the body of knowledge of the pathway and preparation of the NP workforce presented as a descriptive evaluation of the pilot NP transition programme. The design of the programme and evaluation was conducted by the authors and would have benefitted from external review. Future evaluation should seek the views of employers and leaders. Our paper reports on just one aspect of preparation of the NP workforce and needs to be considered within a continuum of work to promote a pathway of NP preparation.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Our experience of developing, implementing, and evaluating a transition programme for NPs in their first year of practice in PHC, together with international evidence, leads us to recommend the following:

-

One-year supported transition programme commencing from time of registration as a NP.

-

Salary contribution for at least 9 months post registration to allow for 20-minute minimum appointments; clinical peer review; access to a NP mentor and professional supervision; develop strong networks across the sector; opportunity to build role visibility; engage with local communities to shape service delivery to support equitable health outcomes.

-

Professional development funding at a standard rate for all NPs (not pro-rated).

-

Post registration courses, at least some of which are NP specific (for example, mental health and addiction, child/youth health, older adults), to advance a range of clinical skills and competencies relevant to their population served.

-

Regular workshops for the transition NP cohorts (monthly for two hours) for peer support; and to provide information and education through guest speakers on a range of topics including navigating transition to practice, negotiating pay and conditions, income generation in primary care, indemnity and professional accountabilities, enhancing service delivery to meet local community health needs, and self-care.

-

-

Support for employing organisations to ensure NP is successfully integrated into the practice, with a shared vision of their work, understanding of NP scope of practice, and guidance on incremental increases in responsibility and patient load reflective of NP’s skill and confidence development.

-

Flexibility of the programme to respond to need of the NPs, prioritise the Māori and Pacific NP workforce, and particularly support those working in underserved, rural, and prioritised communities.

-

Programme leaders with capability to support NPs and providers to trouble-shoot and realise the potential of NP practice.

-

Funded access to NP mentors to discuss clinical cases and support to grow their confidence.

-

Funded support for delivery of post-registration NP education, NP mentorship training, and regional networks of NPs to support NPs transitioning to practice.

Future work is required to develop and evaluate a toolkit, building on existing knowledge, to guide health organisations, funders and policy-makers to provide practical information and guidance on implementing the NP role into health services. Ultimately, we would argue for the NP workforce to be recognised as advanced autonomous clinicians who require well funded vocational education and training (before and post-NP registration) reflective of their contribution as lead providers delivering comprehensive PHC services for Aotearoa New Zealand’s population.

CONCLUSION

Well supported transition to practice is critical to enable NPs to flourish and deliver comprehensive PHC services. This paper provides a descriptive evaluation of the pilot NP transition programme to inform health policy, future programme delivery, employing organisations, and NPs. Given the considerable stress faced by the health sector with high rates of burnout and attrition amongst healthcare workers, including general practitioners, there is an imperative to support NPs to practice to their full potential as advanced clinicians and future leaders and owners of PHC services. Additionally, we know NPs offer the potential to transform PHC services and improve healthcare access and equity. NPs and their professional organisations need to be at the forefront of policy development and strongly resist efforts that determine or undermine professional standards and status. Given the Government’s welcomed intent to increase the number of NPs in primary healthcare, investing more (not less) in their education and training while building on existing professional evidence and knowledge would offer greater likelihood of providing high quality and safe patient care.

Funding

The pilot NP transition programme was funded by Health New Zealand for 2023 and 2024. No funding was received for evaluation.

Conflicts of interest

SA and JD were co-leaders of the national EN/NP Workforce Programme. SA is a chief editor of Nursing Praxis Aotearoa New Zealand; and EK is a board member.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)