INTRODUCTION

Health care organisations face significant financial costs related to the recruitment, onboarding, and induction of nursing staff (Halter et al., 2017). Beyond financial implications, nursing turnover also leads to substantial non-financial consequences, such as diminished quality of care (Peng et al., 2023), decreased staff productivity (Jones et al., 2015), and reduced morale among remaining staff (Ghandour et al., 2019). Given these considerable risks, retaining nursing staff is a critical priority.

One effective strategy to support staff retention is the implementation of a well-structured induction programme at the start of a new role (C. P. R. Scott et al., 2022). Such programmes can reduce stress experienced by new employees and support their integration into the workplace. Key factors in a successful transition include role clarity, self-efficacy, and social acceptance (Bauer et al., 2007), all of which can be enhanced through a comprehensive induction process that facilitates both role orientation and organisational socialisation. The importance of delivering effective induction for new staff is not only essential for workforce integration, it is increasingly recognised as fostering organisational performance. In healthcare, effective induction is linked to increased staff satisfaction (Bowers et al., 2023), lower attrition (De Vries et al., 2023), and improved patient safety (G. Scott et al., 2022).

Learning in a new role and in a new environment can be particularly challenging, especially in complex specialties such as critical care where the acquisition of advanced knowledge is essential (Stewart, 2021). This demands significant investment from both new staff and their preceptors. In response to these challenges, eLearning is increasingly being adopted as a component of induction programmes. This paper presents the findings of a 12-month evaluation of the first national eLearning induction programme for critical care in Aotearoa New Zealand.

BACKGROUND

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health system and on the education of health professionals is well-reported (Frenk et al., 2022), bringing increased attention to global healthcare workforce challenges (Bourgeault et al., 2020). In Aotearoa New Zealand, recognition of the under-provision in critical care services led to significant additional government investment increasing critical care bed availability by 30% (New Zealand Government, 2021) requiring an extra 88 critical care beds. Given that 5.3 FTE nurses are required to staff one intensive care unit (ICU) bed 24 hours per day, this resulted in a substantial number of nurses being recruited and trained (Longmore, 2023).

Although many ICUs already had structured induction programmes in place, the scale of this onboarding was unprecedented. To support the rapid orientation of staff, a national eLearning Programme (Induction) in Critical Care New Zealand (EPICCNZ) was commissioned by Health New Zealand/Te Whatu Ora to provide an accessible and current clinical introduction to the speciality. Whilst the target audience was nursing, modules were developed with, and made available for, allied health and medical staff.

To deliver EPICCNZ, a project team was established of critical care nurses and learning design and technology experts. Over a 15-month period, and with widespread consultation and detailed quality checks, nine e-learning modules were written and developed using a rigorous project implementation plan. The interactive, multimedia modules focused on clinical knowledge acquisition. Four modules explored core care principles (such as assessment, foundations of care) while five modules focussed on body systems (including respiratory, cardiac, renal). Module sections detailed anatomy and physiology, conditions, diagnostics, and interventions, each with a completion time of one to two hours. The modules were launched across the three national Learning Management Systems (LMS) on 22 April 2024. Local educators on each unit determined: how the modules were integrated into local induction programmes; when the modules were undertaken; and in what order. A further two specialist modules were designed and released by December 2024. With detail of the implementation process already published (Klap et al., 2024), this paper reports on what is known about the uptake and impact of EPICCNZ during the first 12 months.

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

The aim of this study was to evaluate uptake and impact of EPICCNZ in the first year since it’s go-live date in April, 2024.

Study objectives were to:

-

report on uptake of the EPICCNZ programme

-

describe user satisfaction and relevancy of the EPICCNZ modules

-

explore user experience of EPICCNZ programme including any perceived change in knowledge and understanding of practice in Aotearoa New Zealand.

METHODS

Study design

Kirkpatrick’s model of training evaluation (1959) informed the study aims, design and data collection. This model has traditionally been used to provide managers with a systematic and efficient method for evaluating whether training has improved employee and organisational outcomes (Cahapay, 2021). It has been widely used in the evaluation of education including training programmes (Masood & Usmani, 2015), blended learning environments (Embi et al., 2017) and used across the health disciplines (Huang et al., 2022; Liao & Hsu, 2019).

The model comprises of four levels each with a different emphasis and evaluation timeframe (Kirkpatrick & Kirkpatrick, 2006). Level 1 (reaction) assesses immediate participants’ satisfaction and their perceptions of the training programme. Level 2 (learning) measures the extent to which participants have acquired knowledge, skills, and values on completion of the training. Level 3 (behaviour) assesses changes in participants’ work-related behaviours resulting from the programme and is typically undertaken months after training. Level 4 (impact) examines longer-term institutional outcomes indicating effects attributable to the training programme. Table 1 illustrates how the shorter-term Levels 1 and 2 informed this evaluation.

Study objectives were to:

-

report on uptake of the EPICCNZ programme

-

describe user satisfaction and relevancy of the EPICCNZ modules

-

explore user experience of EPICCNZ programme including any perceived change in knowledge and understanding of practice in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The evaluation used a self-report design with learner evaluation feedback and course report data.

Study participant

Study participants were health care staff from across Aotearoa New Zealand who completed any of the EPICCNZ modules 22 April 2024 – 21 April 2025.

Data collection

Data was collected over the first 12-months from the programme’s go-live in April 2024. Enrolment and completion data was collated across the three national LMS to identify the number of learners enrolled in each module and the number of completions for each module. Demographic data was collected for location and healthcare profession of module users.

Module users were asked to provide feedback on their satisfaction with, and relevancy of, the EPICCNZ modules. Using a five point Likert scale, feedback questions were embedded into the LMS at the end of each module. These questions determined user rating on module quality, content, functionality, level of information and whether the module helped learning. The Likert scale rating system allowed users to select from strong agreement to strong disagreement including a neutral option. A free text box was available to collect any qualitative comments.

Users were also given opportunity to provide feedback on overall experience of the EPICCNZ programme on completion of their final module. Data was collected by asking the user to reflect on their knowledge level about critical care at the start of the modules and their knowledge level at the end of their last module. Using a five point Likert scale (a lot, somewhat, a little, none, neutral), users were asked questions about knowledge development, programme usefulness, overall learning, understanding about culturally safe practice at the bedside and understanding about professional practice expectations at the bedside in Aotearoa New Zealand. A free text box was available to collect any qualitative comments.

Data analysis

Monthly module data reports were generated by each LMS system administrator, anonymised and sent to the project team. Using Microsoft Excel spreadsheets, the reports were collated with frequency counts, categorical and numerical data variables used to describe and report on quantitative data.

All qualitative data (free text feedback) was collated onto a separate Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. After an initial read through of all comments, content analysis was undertaken (Kleinheskel et al., 2020) where similar remarks were grouped together. The largest category then underwent a further level of analysis. Study team (TK, LB, GR, MC) meetings were held to discuss results and agree findings from this review.

Ethics

Submission of feedback via the LMS was entirely voluntary. Participation in feedback was not required to secure continued professional development hours and did not prevent learners from completing the module. No personal details were shared as the project team received de-identified, anonymised reports from the LMS administrators. The study proposal was approved by the Human Ethics Committee at Te Herenga Waka - Victoria University of Wellington (No. 31545). In writing this paper, we consulted and adhered to the COPE (Committee on Publication Ethics) Core Practices.

Reporting systems at the time did not enable collection on data ethnicity. We were therefore unable to analyse and report on data as it related to Māori or other ethnicities.

RESULTS

Twelve-month evaluation results are presented under the three study objectives:

-

uptake of EPICCNZ

-

user satisfaction and relevancy of the EPICCNZ modules

-

user experience of the EPICCNZ programme.

Uptake of EPICCNZ

Data from the first 12 months of EPICCNZ identified a significant uptake of the modules across Aotearoa New Zealand. At end of month 12, 6189 modules had been completed from 8586 module enrolments; a 72% completion rate. Module completion rates gradually increased, rising from 56% in month 1 to 68% by month 6. To note, we were unable to retrieve data on the total number of individuals who accessed EPICCNZ. This was due to reporting limitations across the LMS when collating data from complex programmes with multiple modules, including EPICCNZ.

Analysis of module completions demonstrated a mean monthly average of 583 completions for the first six months (including a peak of 669 completions at month five). With a predictable completion drop occurring during the southern hemisphere holiday period (n=262 for month nine), module completions have since averaged 427/month. Collated data from across all three LMS at month 12 identified that Module 1 (Introduction to critical care), Module 2 (Assessment at the bedside) and Module 5 (Respiratory) had the highest number of completions. Modules covering more specialist areas, such as Module 9 (Special populations) and the more recently developed Module 10 (Critical care outreach) and Module 11 (Interhospital transport) had lower uptake (Figure 1).

Review of LMS data reports identified all 24 critical care areas across Aotearoa New Zealand had module enrolments and completions. Generally smaller units had less enrolments and completions due to a reduced staffing base. One exception to this was a secondary unit with high uptake. This was due to local practice that all staff (not just onboarding staff) were being encouraged to undertake EPICCNZ modules.

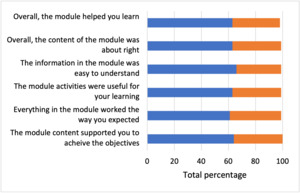

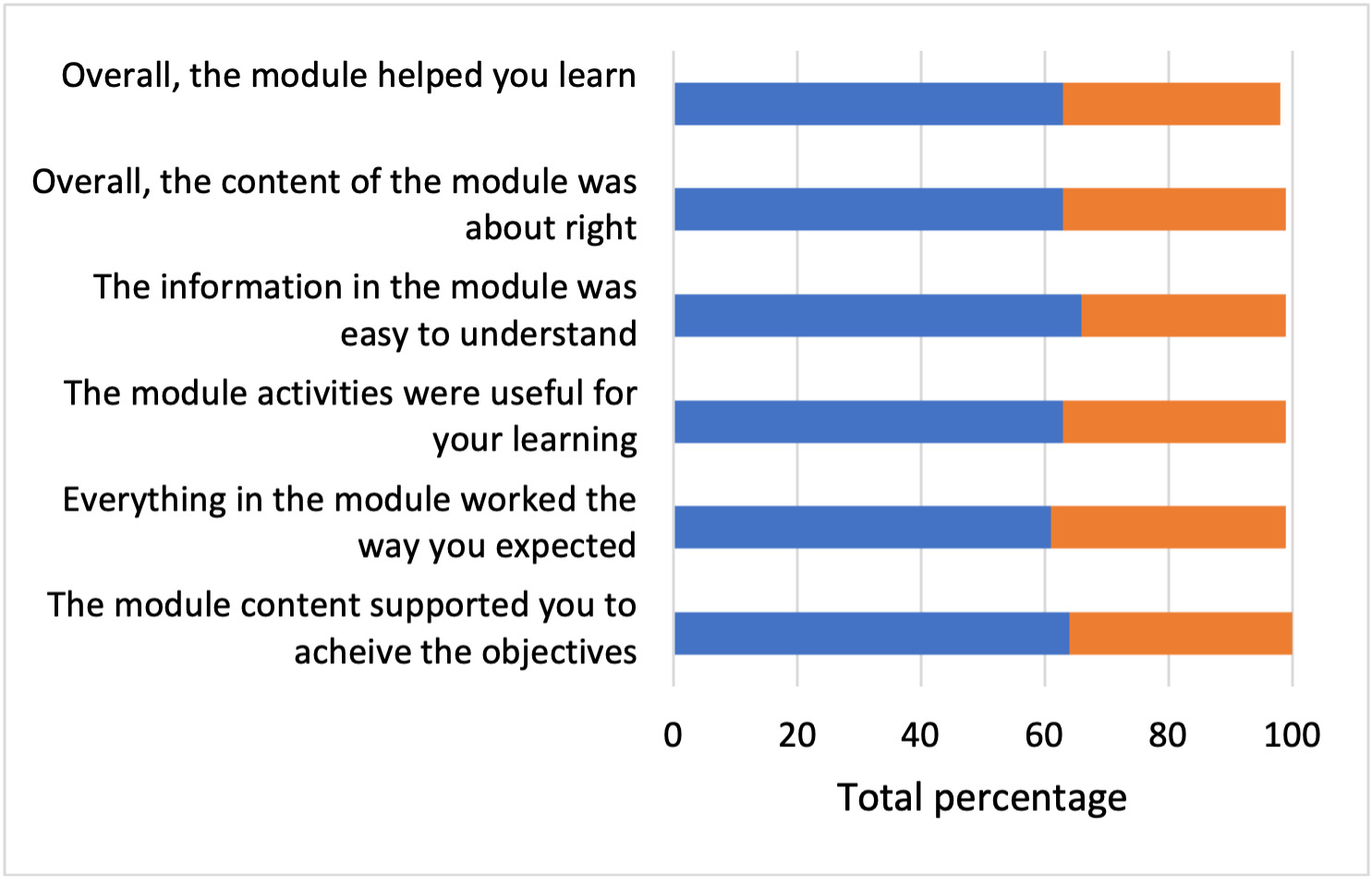

The largest professional group completing EPICCNZ modules were nurses (77%) followed by allied health staff including physiotherapists, pharmacists, dieticians, speech and language therapists (4%). A small number of health care assistants and medical staff had also completed modules. Due to LMS system limitations, 12% of role/discipline data fields were incomplete (Figure 2).

User satisfaction and relevancy of EPICCNZ modules

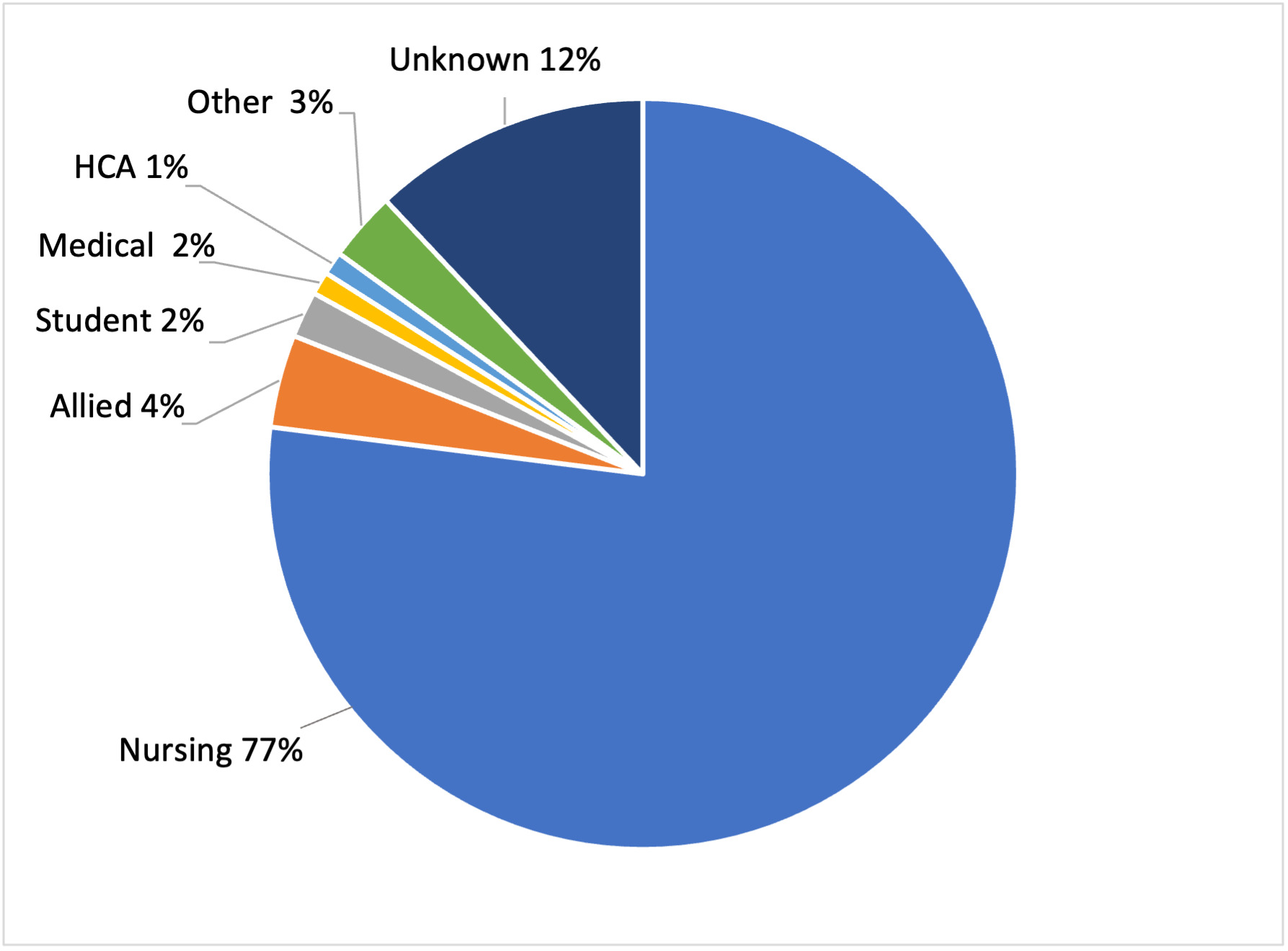

Over the 12-month period, 3123 individual module feedback responses were completed, with an overall 50.5% module feedback response rate. 100% of module users agreed or strongly agreed that module objectives were met with 99% of module users identifying that content was easy to understand and was presented at the right level (Figure 3).

User experience of the EPICCNZ programme

Over the 12-month period, 497 users submitted response to programme feedback questions on completion of their last module. Over 95% of respondents reported a positive user experience, stating that EPICCNZ enhanced their understanding of professional practice expectations and was relevant to their learning. Additionally, 89% (n=441) agreed it supported their understanding of culturally safe practice within Aotearoa New Zealand.

In addition to quantitative responses, 352 free-text comments (excluding nil/no/not applicable responses) were analysed. A pragmatic categorisation (endorsement, content change, technical issues, negative critique) supported early prioritisation and problem-solving of the comments. Most feedback (77%, n=271) consisted of positive endorsements about EPICCNZ. Fourteen percent (n=48) suggested content changes, such as correcting spelling or aligning content with local practice. Technical issues were reported in 2.5% (n=11) of comments and these were addressed. Four percent (n=13) offered negative critique including feedback from experienced nurses who found limited new learning and from new critical care staff who found the amount of new learning challenging. Nine comments (2.5%) were incomplete.

Due to the large number of endorsement comments, further content analysis was conducted on these. Key themes developed were: knowledge development (30%, n=82); module design and style (15%, n=39); timing of learning (12%, n=35); positive learning experience (8%, n=22); increased confidence (2%, n=5); and general feedback (33%, n=88) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Best induction practices in healthcare should include role-specific education with clear objectives, delivered using theoretical and applied practical components supported by a preceptor (Sanchez et al., 2020). Given that successful face-to-face induction education is becoming increasingly challenging for new staff and preceptors due to workloads, eLearning provides one solution to mitigate these constraints (Bishop et al., 2019) bringing with it greater access to education and improvement in quality learning experiences (Kaisara et al., 2024).

Data from this evaluation study demonstrates wide engagement with EPICCNZ in its first 12 months. With high numbers of module enrolments and completions, there was uptake of EPICCNZ across all critical care areas in Aotearoa. As an eLearning programme, EPICCNZ was specifically designed for learners who, under guidance of local educators, could select modules of most interest or relevance to their role. In this way, modules were designed to provide flexible learning about when, how, and how long module users engaged. This is important as learners who are in control of their own educational journey and who are prepared for their role, are more likely to engage in the workplace and demonstrate intrinsic learning motivation (Klose et al., 2024).

Intrinsic learning motivation is an important consideration as it is closely linked with higher programme completion rates (Musa et al., 2024). It is therefore interesting that EPICCNZ modules had a high completion rate (72%) over the first 12 months. Before online eLearning programmes became common place, attrition rates in education varied hugely with 20-60% rates of non-completion (Levy, 2007). With increased access to internet-enabled devices, the use of online learning has expanded significantly (Williams et al., 2022). Research indicates that eLearning delivered at the point of major need, such as during the COVID-19 surge workforce training (Australian Government Department of Health, 2020), and major service expansion in the case of EPICCNZ, achieves higher completion rates. Although 28% of staff did not complete the modules, this figure includes staff still working through modules to completion in month 12. It also included experienced or non-critical care staff who, after enrolling and reviewing the modules, found them unsuitable for their learning needs.

The uptake of EPICCNZ across time indicates that modules were undertaken in chronological order (Module 1 to Module 9) with the number of monthly module completions levelling off after month 10. This may have been influenced by the majority of new staff having been onboarded by then. It is also worth noting that month 10 coincided with a national health workforce hiring freeze. The lower number of enrolments for modules 9-11 (Special populations, Critical care outreach, Interhospital transfer) is expected given that less staff will want to undertake clinical modules with a more specialist focus.

Educational literature highlights the critical role of user feedback in assessing course quality and effectiveness. Studies report feedback response rates ranging between 40% and 75% (Sataloff & Vontela, 2021) with 40% generally considered sufficient to ensure reliable and valid feedback (Story & Tait, 2019). EPICCNZ’s 50.5% individual module feedback rate exceeds this threshold strengthening confidence in the feedback’s reliability.

Evaluation of the EPICCNZ modules identifies high user satisfaction with both content and presentation. Aligning with sound design principles (Marks et al., 2021), each module was designed to focus on specific knowledge areas, divided into sections with use of knowledge checks to allow users to learn at their own pace. As advised in the programme and consistent with best practice (Camilleri et al., 2022), practical follow-up sessions with more experienced staff were recommended to consolidate learning.

Qualitative feedback from free-text responses deepened understanding of user ratings on module usefulness and impact. Analysis identified that EPICCNZ supported knowledge development, was valuable for induction and refresher learning, featured engaging design, provided a positive learning experience, and boosted user confidence. This feedback is important because it demonstrates how EPICCNZ adheres to the key principles of the research-based Universal Design for Learning framework (CAST, 2024) by using culturally relevant content and self-reflection activities with use of varied learning formats. By following these principles, EPICCNZ has enhanced learners’ experiences, ensuring they can effectively access, engage with, and succeed in meaningful learning opportunities.

This evaluation, consistent with much of the education literature, focused on key eLearning outcomes of user satisfaction (Liaw, 2008), knowledge acquisition (Bennett et al., 2014) and clinical skills development (Blackman et al., 2014). As such, the evaluation was focussed on Level 1 (reaction) and Level 2 (learning) of Kirkpatrick’s model (1959). It did not extend to Level 3 (behaviour change) or Level 4 (organisational impact). This is a limitation of this study and further research will be necessary to determine longer-term impacts including potential changes in organisational outcomes such as culture, workforce development and retention behaviour.

There are other limitations in this evaluation that require acknowledging. Use of self-report studies are well-established in the field of education but have noted drawbacks. Perhaps the most recognised is that self-reporting is under the respondents’ control and therefore subject to response biases including social desirability and memory bias (Peckrun, 2020). Use of other data collection methods, such as interview or pre-test and post-test measurement rating, would have been useful. Working with existing data reporting systems was a further challenge and this resulted in areas of missing data.

CONCLUSION

This evaluation demonstrates that a national eLearning induction programme, such as EPICCNZ, can have strong uptake, be highly relevant, and generate significant levels of satisfaction in users. As such, this study adds to the body of literature identifying that eLearning is increasingly used in education increasing learner flexibility and interactivity. However, given the increased use of this learning modality, safeguards must be put in place to ensure staff do not become fatigued in using eLearning to meet professional and organisational learning needs.

EPICCNZ is recognised as a successful clinical programme for onboarding staff into critical care. There is anecdotal evidence of EPICCNZ integration into established induction pathways enabling educators to work in different ways to support new staff. With this, it is hoped that improved knowledge gained through EPICCNZ will have longterm effects of influencing staff behaviour and ultimately, have positive impact on patient outcomes.

Acknowledgement

In undertaking this evaluation, the authors acknowledge work undertaken by the Learning Design and Technology team at Wellington Hospital and the Learning Management Systems Administrators in setting up the feedback question functionalities and EPICCNZ reporting. Thanks are extended to all who have taken time to provide feedback on EPICCNZ, thereby informing this study.

Funding

EPICCNZ was originally supported through generous funding from the Critical Care Sector Advisory Group, Health New Zealand Te Whatu Ora.

Conflict of interest

None