INTRODUCTION

Responsible and ethical integration of generative artificial intelligence (Gen-AI) into teaching and learning is now a key concern throughout the education sector globally, especially in tertiary education (Farrelly & Baker, 2023; Godsk & Møller, 2025; Holmes et al., 2022; Ivanova et al., 2024). While there are legitimate concerns about limitations and misuses, the benefits are considerable (Kadaruddin, 2023; Meyer et al., 2023). Gen-AI can be used to support personalised learning, adaptive tutoring and interactive learning (Baidoo-Anu & Owusu Ansah, 2023) and has transformative potential for all healthcare education (Abd-alrazaq et al., 2023; Ahmed, 2024; Furey et al., 2024; Glauberman et al., 2023). It has been suggested that AI and chatbots “have the potential to revolutionise nursing education and the nursing profession” (Srinivasan et al., 2024, p. 5).

Healthcare and nursing education research has focussed on the preparation of graduates to use AI as digital healthcare practitioners. Indeed, it has been noted that the Nursing Council of New Zealand “clearly expects nurses to understand and use digital health” (Honey & Collins, 2025, para. 4). AI can be used for simulated patient scenarios as well as for supporting healthcare for patients and clients more generally through digital twins and AI-powered chatbots that can assist with diagnoses and advice about treatment (Pang et al., 2023; Srinivasan et al., 2024).

Artificial intelligence applications and adaptive learning technologies can provide individually tailored support to students accommodating their learning preferences. They can augment the expertise of teachers (Luckin & Holmes, 2016), generate interactive learning tools for in-class teaching and assist with writing (Meyer et al., 2023). There is burgeoning literature on the use of chatbots for personalised learning experiences (see for example, Adams & Riddle, 2023; Glauberman et al., 2023; Ilieva et al., 2023; Liu, 2023; Naznin et al., 2025) and on the need for professional development for educators in AI technologies, as well as AI literacy capability building for both students and educators in the use of Gen-AI (Abd-alrazaq et al., 2023).

A separate and distinct area of research is the use of chatbots for personalised learning in health and nursing education (see for example, Park et al., 2024; Ramírez-Baraldes et al., 2025; Srinivasan et al., 2024). Subject-specific research is important because of different pedagogies related to teaching different subjects, the nature of course content, student demographics, and the context of the health and health policy environment. In Aotearoa New Zealand, context-specific considerations should necessarily influence how AI-powered technologies are deployed in education, such as Te Tiriti o Waitangi, and legislative requirements, such as the Privacy Act (2020). Nursing education encompasses a wide range of content matter including anatomy and physiology, pharmacology, and culturally safe clinical practice. Students enrolling in a bachelor of nursing degree come from a wide range of ethnicities and learning experiences. For many, the science content in the curriculum is challenging (Jensen et al., 2018) and is an area of nursing education where the use of AI agents is of potential benefit.

Although published in 2020, well before the advent of Gen-AI and Large Language Models (LLMs), Aotearoa New Zealand’s Tertiary Education Strategy remains relevant for evaluating AI-powered innovations in education. The Strategy contains five objectives: barrier-free access; learners at the centre; quality teaching and leadership; future of learning and work; and world-class inclusive public education (Ministry of Education, 2020). For tertiary education organisations, as indeed for primary and secondary education providers, AI can potentially remove barriers (especially for students with diverse learning needs) and can ensure individual learners can be given tailored support in a way that has not been possible at scale. With the huge implications for teaching and learning, educators must quickly upskill in both use of Gen-AI and other AI-powered technology and also develop their own and their students’ critical thinking about AI. Finally, learning about AI and how to use it will be increasingly important for employment.

EDUCATIONAL INNOVATION USING CHATBOTS

In early 2024, an opportunity for Toi Ohomai nursing educators arose to participate in a trial of Gen-AI chatbots for personalised learning using the Cogniti artificial intelligence platform (Cogniti.ai) (https://cogniti.ai/) developed at the University of Sydney (Liu, 2023). Cogniti.ai is designed for teachers and educators to custom-build chatbot agents in context-sensitive and specific ways. Cogniti.ai was trialled in a range of tertiary education institutions in Australia and a small number of tertiary institutions in Aotearoa New Zealand. A mini-symposium in February 2024 allowed educators to share preliminary insights at a very early stage of using of Cogniti.ai (University of Sydney, 2024). Because Gen-AI use in Aotearoa New Zealand in early 2024 was still emerging, there was a considerable vacuum of knowledge about its impact on learning and learners, particularly so in relation to vocational education (Chan, 2025).

In a 2024 study, students in their final year of a bachelor of nursing programme used public Gen-AI tools to assist completing six concept maps in their final clinical placement (Bowen-Withington, 2025). There were four participants and the task was for a formative assessment. While this was a different use of Gen-AI to support learners than in our own trial with Cogniti.ai, a key conclusion of the study noted:

Artificial intelligence technologies (AIT) have tremendous potential to transform the way we train future health professionals, in particular undergraduate nursing students. In undergraduate nursing education, AIT cannot replace the valuable role of academic nurse educators, or authentic experiences with health consumers. However, AIT has the potential to enhance educational effectiveness by promoting transformational self-directed learning, provide improved engagement and foster deeper learning and reflective practice… Subsequently it is important that educators continue to explore, innovate, and adapt teaching methods to provide nursing students with the best possible education (Bowen-Withington, 2025, p. 115).

Discipline-specific research is important because of the subject matter taught and because student cohort demographics generally vary. At Toi Ohomai, we wanted to find ways to enhance learning of anatomy and physiology of year one bachelor of nursing students, given the challenges often experienced by students in these subject areas. Gen-AI chatbots, designed through Cogniti.ai, ensured protected content and student data by being hosted within the institution as well as providing a configuration interface for educators and learning designers to mediate and curate the chatbot content and behaviours.

In the case of Toi Ohomai, as in many education organisations, there are strict controls on use of Gen-AI, because of regulatory obligations, privacy legislation and data sovereignty. With Cogniti.ai, all student conversations are stored in an institution’s own private network, ensuring privacy and safeguards for student data and course content, while still leveraging the capabilities of the latest Gen-AI models. Educators or designers add their own prompts and course resources, which are then saved, with the resulting link to a private chatbot then published to individual courses. Importantly, because the chatbot uses and refers to course content provided on the Learning Management System the risk of incorrect information is substantially reduced, if not eliminated.

With the Tertiary Education Strategy (Ministry of Education, 2020) as a reference point, and to ensure a robust evaluation of chatbot use in nursing education, an exploratory study was undertaken that focused on the question: What is the impact of access to chatbot providing personalised learning support on Year One nursing students’ learning in a nursing science course?

Year One in an undergraduate degree is an important site for research on Gen-AI as it is an early stage in students’ enrolment in vocational training and, as such, an important juncture for developing AI literacy. In vocational education and training (VET) the curriculum is applied and focused on the pathway to employment. Research about the use of chatbots in other, less applied subject areas may not fully capture the experience of users in the VET sector. Therefore, the research we undertook focused specifically on students in the VET sector in the early stages of tertiary study recognising these users will have different needs and experiences from those in postgraduate or more senior undergraduate courses. In terms of demographics, the Bachelor of Nursing programme at Toi Ohomai attracts students from a diversity of ethnic backgrounds including Māori, NZ European (Pākehā) and international students. In addition, as the cohort is overwhelmingly female, the research meant that female perspectives of AI were captured whereas they might be under-represented in research carried out in some other subjects.

METHODS

The exploratory study evaluated the use of a Gen-AI Cogniti chatbot, as an educational innovation, with a single cohort of students in semester one in their first-year nursing science course at Toi Ohomai (February to July 2024). A chatbot was configured to be a student support and mentor, to assist students in understanding the course content, and as preparation for two summative tests. The system prompt was adapted from prompts by Mollick and Mollick (2024). (See Supplementary File for the full system prompt.)

Data collection

Descriptive quantitative and qualitative data were generated by the Cogniti.ai platform and took the form of conversation or chat records and logs of when conversations took place, allowing us to understand the content of, and patterns of use, such as student behaviour. Other quantitative data were secondary data in the form of student test results. An anonymous online survey of students provided further descriptive quantitative and qualitative data about student perceptions.

Intervention

Within the first year nursing science course, students are given two tests during semester one. The results of each test contribute 16.5% to their final mark of the course. A chatbot was created to assist students to understand the course content before the tests.

The chatbot used GPT-4, a large multimodal model (developed by OpenAI https://openai.com/index/gpt-4/), which was the most current model available at the time. Nursing course teachers and academic support staff collaborated to author their chatbot using a prompt as a word or text file that describes the behaviours of the chatbot and is customised with links to the online course resources. The entire prompt is saved as a unique private ‘chatbot’ and a link to this is then published to the course. (See Supplementary File for the full system prompt.)

Additional guidance for the chatbot was anchoring its resources to documents from the course. These resources were accessed by the chatbot in a process called retrieval augmented generation (RAG). Relevant information is identified and retrieved from documents based on a user’s query and is combined to create a more contextually rich prompt.

Student onboarding

A face-to-face induction for the class was provided by the Toi Ohomai academic support team including an explanation of how the chatbot was configured, an overview of the limitations of Gen-AI, and information about who would view the students’ conversations. Only the educators/teachers could view the conversations; students could not see each other’s chats. Onboarding for students also included examples and tips on how to get better formatted outputs while using the chatbot. The course teacher worked closely with academic support prior to and during the student onboarding and throughout the pilot. After the launch of each chatbot the chat conversations were monitored for abuse or unintended responses.

Data Collection

Qualitative data was gathered through an online survey distributed to students about their use of the chatbot. The invitation to voluntarily participate was made at the onboarding session and a link in their online course. A link to the online survey was also embedded into the prompt so the invitation would be given to students during their chatbot sessions. The survey was a combination of questions using a Likert scale (1-5) and open feedback questions with some demographic questions. Between 25 March and 1 August 2024 there were 55 respondents from 127 students.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this research was granted by the Toi Ohomai Research Committee for a study of student behaviour and perceptions of AI-powered personalised learning support (Ref: TRC 2024.010).

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated using Excel to analyse survey data on student perceptions. Desktop analysis was undertaken of changes in individual marks across the entire class between the first test and second test. We also compared the 2024 cohort results with previous cohorts’ performance in the same assessments. Additionally, analysis focussed on students who had the most change and least change in test results, and on how those students used the chatbot, using the logs and conversation records available to teaching staff.

FINDINGS

We outline findings starting with basic indicators of student behaviour, namely, the timing of student conversations and the nature of the conversations. We then present data on student perceptions of the value of the chatbot. This is followed by analysis of data on test results for the 2024 cohort and a comparison with previous cohorts. The section concludes with a brief comment about other factors that might influence the change in test results.

Usage

Cogniti.ai stores a record of all student conversations, and the time when each student used the chatbots, for teachers to view or download. Records showed students used it the most in evening and early mornings, outside of class-facing hours (Figure 1).

Student conversations with the chatbot

The chatbot was first released to students two weeks before the first test and had 30 active student users before the first test. Usage dropped after the first test on 8 April 2024 but picked up again prior to the second test on 10 June 2024. The second test was on different topics, still within nursing science. The key difference between the two tests was the increase in use from 30 students to 100 students, out of a cohort of 127 students within the course. In the weeks prior to the second test, there were 1200 separate conversations from 100 students with a strong emphasis on self-test and check, with an average duration of 20 minutes per student session (Table 1).

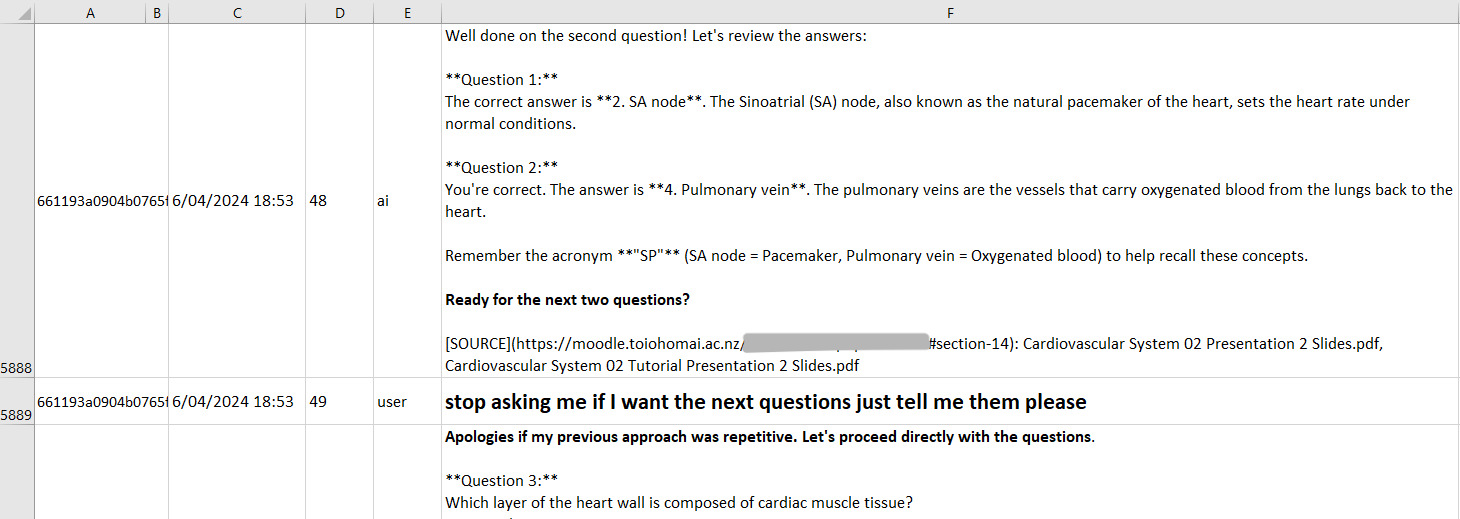

Also of interest were the conversations themselves, which showed emotional engagement, and for some students, frustration that the chatbot always checked with the student before moving to further questions (Figure 2). The chatbot was behaving in the way the prompt was written and led to further modification of the system prompt to add flexibility in responses based on student progression and session length.

Perceptions

Of 50 students responding to a question on use or helpfulness, 62% gave it the highest rating saying it was “very helpful”. When students were asked if they would like to continue to use this type of chatbot, 91% of the respondents (n=36) gave a 4 or 5 out of 5 on a Likert scale, with two-thirds rating it a 5/5, considering chatbots as “essential for my study now” (Figure 3).

Student perceptions in using chatbots for learning support also came from open-ended questions in the survey with 44 separate responses. The twelve quotes (Table 2) characterise the overall themes from student feedback.

Test results

As part of our analysis of the cohort use, perceptions and results, we observed an overall improvement between individual results from the student test 1 on 8 April and test 2 on 10 June for the 2024 cohort with access to the chatbots, compared with the previous two years. Figure 4 shows approximately 70% of students increased their test scores for test 2 in 2024 compared with test 1; whereas only a few students in the previous two years (2022 and 2023) showed any improvement in their test scores between test 1 and 2. We note there was no control group in this exploratory study, and there were several confounding factors that could have contributed to the changes observed.

The student who had the largest change in results between the two tests went from 36% in test 1 to 84% in test 2 and started using the chatbot a month before the second test in four separate sessions. Their first request to the chatbot was “give me 50 questions…” and then proceeded to go through a series of test and check sessions. Another student who went from 50% in test 1 to 54% in test 2, only had one session of 30 rounds, then toward the end of their session asked the chatbot to identify their knowledge gaps, with subsequent questions focussed on these gaps.

Limitations

Confounding factors such as teaching style, student study habits and characteristics of the 2024 student cohort could all have influenced the improved academic outcomes in the 2024 nursing science course. However, student feedback from this exploratory study indicates that access to personalised learning support was seen as very valuable for their preparation for the summative tests. This use of Gen-AI is only for learning support as part of preparation for tests. It could not in any way substitute for the individual effort each student needed to make in the test setting. The summative tests could not be done using Gen-AI. A more detailed analysis of the specific impact on individual student results would be useful and is another area of further research, such as by identifying the contribution chatbots make to to improving their results in subsequent tests.

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

Earlier this year, authors of an editorial in this journal recognised the value of chatbots as study assistants and the positive effect on student’s motivation to learn and capacity for self-directed learning (Honey & Collins, 2025). Our findings provide preliminary empirical evidence to support this assessment of the potential for AI to provide personalised learning support. The editorial also highlighted some questions that they said were unanswered but worthy of debate. These questions included whether use of AI tools such as ChatGPT constitutes cheating or helping student development, and whether AI can identify students needing academic support (Honey & Collins, 2025). There is no question that inappropriate use of AI tools by students is problematic, and is not helped if there is institutional delay in updating assessment formats and academic policies. Our research was undertaken using a privately-hosted AI tool designed for use in an education setting (as distinct from generic or public tools), and is configured to protect student data and institutional content. The use of Cogniti.ai by students in a structured environment, with teacher input and the opportunity to discuss appropriate use can contribute to a greater understanding of AI literacy and the relationship between academic integrity and generative AI utilisation during academic assessment.

Educational values must inform and guide the uptake of technology and indeed pedagogical change. For Aotearoa New Zealand these values and considerations include transparency, privacy, and managing risk by avoiding public Gen-AI tools (Department of Internal Affairs et al., 2023). The partnership requirements in the Education and Training Act 2020 Schedule 13 are described by Adams & Riddle (2023) as “respect for Māori aspirations, values and property, accepting that thinking through legal and data provenance issues needs to be part of the design process, not an afterthought” (p. 126). While data sovereignty and privacy are enabled by using Cogniti.ai, other issues such as cultural safety and implicit cultural-bias, discussed by Adams and Riddle, are only slowly being addressed with localised training and Indigenous language models. Careful design of the chatbot (system prompt and resources) is important to balance these impacts, particularly in nursing to ensure cultural safety is promoted with Te Tiriti o Waitangi principles embedded.

A chatbot that is configured for a particular learning task such as a summative assessment is readily accessed at any time by students, often outside of class time and educators’ working hours. However as new applications using AI emerge, it is important to ensure there is equity of access to this technology, particularly those considered digitally disadvantaged (Khowaja et al., 2024). Further, more research is needed on how students with different linguistic and academic abilities use chatbots in different learning activities. The utilisation of the chatbot and monitoring of chatbot conversations provided teaching staff with feedback on course content that students found challenging due to the complexity of content. Based on this feedback teachers modified teaching materials on the learning management system to support student learning. Using teacher-configurable chatbots aligns Gen-AI technology with scalable student support especially useful for larger cohorts. Personalised learning support through Gen-AI is a part of the ongoing technological evolution of intelligent tutoring systems. We anticipate institutions will adopt Gen-AI chatbots more widely across academic programmes and concurrently we need to be actively researching and providing guidance on ways to ensure students are taught how to use Gen-AI to best support their own learning objectives.

We observed differences in the way students engaged with a chatbot (such as the types of questions they asked). The mode of learning with immediate feedback allowed for both high-volume iterative feedback but also opportunities for deeper analysis and self-reflection by students to identify their relative strengths and weaknesses. Test results improved for 70% of our students, which could support the assertion that learning improves when students test and restest knowledge, provided that corrective feedback is given highlighting reasoning and concepts, rather than simply correct or incorrect answers (von Hippel, 2024). Enhancing the onboarding and training for all students to optimise the use of the chatbots, including types and content of questions, are important to improve achievement of learning outcomes.

Dell’Acqua et al. (2023) suggested that knowing when to use Gen-AI is arguably more important than access to Gen-AI itself. Therefore, it is imperative that guidance and training is available to both students and teachers so they can more effectively utilise Gen-AI chatbots. Beyond the immediate value as an augmentation to learning support, introducing Gen-AI chatbots into the curriculum contributes to developing AI literacy. This literacy will be essential for other uses of AI in nursing and healthcare for health information and diagnosis. In addition, graduates are very likely to use AI in many aspects of their lives. AI literacy encompasses both knowing how to use AI tools and being aware of the ethical considerations, biases, and limitations of AI tools. As such, it “encourages students to become discerning consumers and creators of AI-generated content, fostering critical thinking and digital citizenship” (Bozkurt, 2023, p. 267).

The growth in multi-mode capabilities also means chatbots can now support an array of tasks and learning modes such as visual comprehension and voice interfaces powering interactive oral assessments. Following the internal dissemination of this research at Toi Ohomai there has been an uptake in use of chatbots in many other courses and subject areas such as law, business, health, beauty, trades, numeracy and te reo Māori grammar (locatives) practice. Cogniti.ai also provides a platform for collaborative research across the tertiary education sector, while allowing each institution to maintain the privacy of their own student data and content within each institution.

With this expanding use of chatbots and building on our experience through this study with BN nursing students, important areas for further research include the influence of teacher AI literacy on the design and use of chatbots and the influence of student AI literacy on engagement with chatbots. Further research is needed on the interface between traditional lectures and chatbots for personalised learning, and the principles for the design of chatbots used in tertiary education settings. Finally, there are important broader questions to explore around changing pedagogy as AI tools increasingly facilitate and foster self-directed learning (Digiacomo et al., 2025).

CONCLUSION

This exploratory study focused on the impact of personalised learning support using a Gen-AI chatbot. The chatbot was specifically designed for nursing students in year one of their BN programme undertaking a nursing science course using course-specific resources and context. Our study provides valuable insights into student behaviour using the chatbot and early indications of improvements in learning. Since this pilot in 2024, the utilisation of chatbots for learning support and the use of Gen-AI more broadly in education has grown rapidly. The emergence of Gen-AI powered chatbots is part of a much longer trend of intelligent tutoring systems (Al Abri, 2025). Considerations relating to the use of Gen-AI in education are not only related to harm minimisation or risk management but must ensure benefits are not withheld (von Hippel, 2024). As Castonguay et al. (2023) argued, “it is urgent for educators to move beyond reactive discussions on regulation, disclosure, and detection and engage in broader dialogue about the possibilities and challenges presented by this type of technology” (p. 3). However, more than dialogue, we recommend hands-on exploration by teachers to design and incorporate chatbots alongside their course content, to surface the benefits described by students themselves.

Acknowledgements

We wish to highlight the essential contribution and support from Professor Danny Liu of the University of Sydney. We also acknowledge the work by Dr Lilach Mollick and Dr Ethan Mollick for their prompts created and generously shared by them, licensed under Creative Commons License Attribution 4.0 International at https://www.moreusefulthings.com/instructor-prompts. Their prompts enabled us to very quickly configure our chatbots and make them available early in Semester 1, 2024 for the trial. Finally, thanks to Bachelor of Nursing lecturers in particular, Debora Moore, and colleagues in Academic Development (in particular, Angela Cuff and team leader Josh Burrell), and Research Officers at Toi Ohomai.

Funding sources

None

Conflicts of interest

None