INTRODUCTION

Trauma - whether a single incident, repeated exposure, or prolonged experience - affects individuals in diverse ways, from subtle impacts to being profoundly damaging (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2014). Grossman et al. (2021) categorise trauma as follows: individual trauma refers to an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that has long-lasting adverse effects on a person’s well-being (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2014); interpersonal trauma includes adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), child maltreatment, domestic and sexual violence, human trafficking, and elder abuse; collective trauma is defined as cultural, historical, social, political, and structural traumas that impact individuals and communities across generations. This scoping review is not limited to a single trauma definition, but reflects any historical trauma experienced by individuals who subsequently access healthcare as adults.

How trauma impacts a person depends on many variables, including personal characteristics, the nature and specifics of the event(s), developmental stage, the personal meaning attributed to the trauma, and sociocultural influences (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2014). While not inevitable, traumatic experiences may disrupt neurological development, physiological processes, behaviours, and relationships throughout life and generations (Isobel & Edwards, 2017). In Aotearoa New Zealand, over half of adults in the general population, and two-thirds of Māori, have experienced trauma in their lifetime, increasing the risk of mental and physical health problems across the lifespan (Flett et al., 2002; Hirini et al., 2005; Te Pou o te Whakaaro Nui, 2018). Adverse childhood events (ACEs) are more prevalent in younger people, those with lower socioeconomic status, and those who identify as Māori, with exposure to any ACE being significantly associated with future intimate partner violence and non-partner violence (Fanslow et al., 2021).

Patients with traumatic life experiences are particularly vulnerable to re-traumatisation in medical encounters (Coles & Jones, 2009). The somaticised memories of trauma are easily triggered during medical treatment and procedures, enabling an onslaught of negative feelings and emotions, particularly for survivors of physical and sexual abuse whose memories are anchored to physical sensations (Gentsch & Kuehn, 2022; van Loon et al., 2004). Examinations may mimic abuse dynamics - being told to relax or feeling trapped - which can prompt memories of lost bodily autonomy (Reeves, 2015).

Trauma-informed care (TIC) is grounded in early trauma theory, which hypothesised that unprocessed memories are stored as psychological reactions to stimuli that recall the traumatic experience (Reeves, 2015). Pioneer researchers, Sigmund Freud, Jean-Martin Charcot, and Pierre Janet, introduced traumatic memories as ‘pathogenic secrets’, where unwanted thoughts intrude into a person’s consciousness (van der Kolk, 2014).

The contemporary TIC approach uses a lens of trauma to understand the range of cognitive, emotional, physical, and behavioural symptoms seen when individuals enter healthcare systems. It is a strengths-based framework that acknowledges the prevalence and impact of traumatic events in clinical practice, emphasising a patient’s sense of safety, control, and autonomy over their life and healthcare decisions (Tracy & Macias-Konstantopoulos, 2021). The implementation of TIC in nursing practice offers numerous benefits, including empowering patients, reducing anxiety and trauma triggers, improving health outcomes, and increasing resilience, all of which potentially minimise the likelihood of re-traumatisation (Goddard et al., 2022). However, despite an increased recognition of the prevalence of traumatic experiences within an individual’s lifetime and the negative impacts on their health, it is not widely understood or implemented, resulting in a gap in literature and practice (Reeves, 2015).

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

This scoping review intended to answer: What do nurses need to know about trauma-informed care (TIC) for patients with a history of traumatic experiences?

Three sub-questions were:

-

How does the literature define TIC?

-

What are nurses’ views and experiences of TIC?

-

What TIC practices can nurses use to support patients?

The key objectives were to: 1) identify gaps in the current literature to ascertain future research priorities; 2) summarise and describe the priorities of nurse-led TIC, exploring what nurses need to know about TIC; and 3) map key findings related to the scoping review question.

METHODS

Arksey and O’Malley (2005) proposed a six-stage methodological framework for conducting a scoping review, which included the following stages: 1) identifying a broad research question; 2) determining relevant studies; 3) establishing a robust study selection criteria; 4) charting the data according to critical issues and themes; 5) collating, summarising, and reporting the results; and lastly; 6) an optional consultation with stakeholders (Pham et al., 2014). However, the Arksey and O’Malley approach is criticised for lacking methodological clarity, especially in data analysis (Osorio et al., 2025). To address these criticisms, the Levac et al. (2010) framework and the JBI scoping review protocol provided additional methodological guidance (Peters et al., 2015). Furthermore, the PRISMA-Scoping Review Checklist was introduced to improve understanding of relevant terminology, core concepts, and critical items for reporting scoping reviews (Tricco et al., 2018).

Search Strategy

Three distinct search strategies were developed and completed to ensure familiarity with the findings and awareness of the keywords and primary concepts. Two pilot search strategies were completed. This approach was guided by Arksey and O’Malley (2005); as literature familiarity increases, researchers may want to redefine search terms and undertake more sensitive searches. A comprehensive search was undertaken in July 2023 using the following databases: CINAHL Ultimate, PubMed, Science Direct, MedLine, and ProQuest Central; and searching relevant article reference lists. Search terms are shown in Table 1. Searches were limited to studies published in English, published within the last ten years, and peer-reviewed.

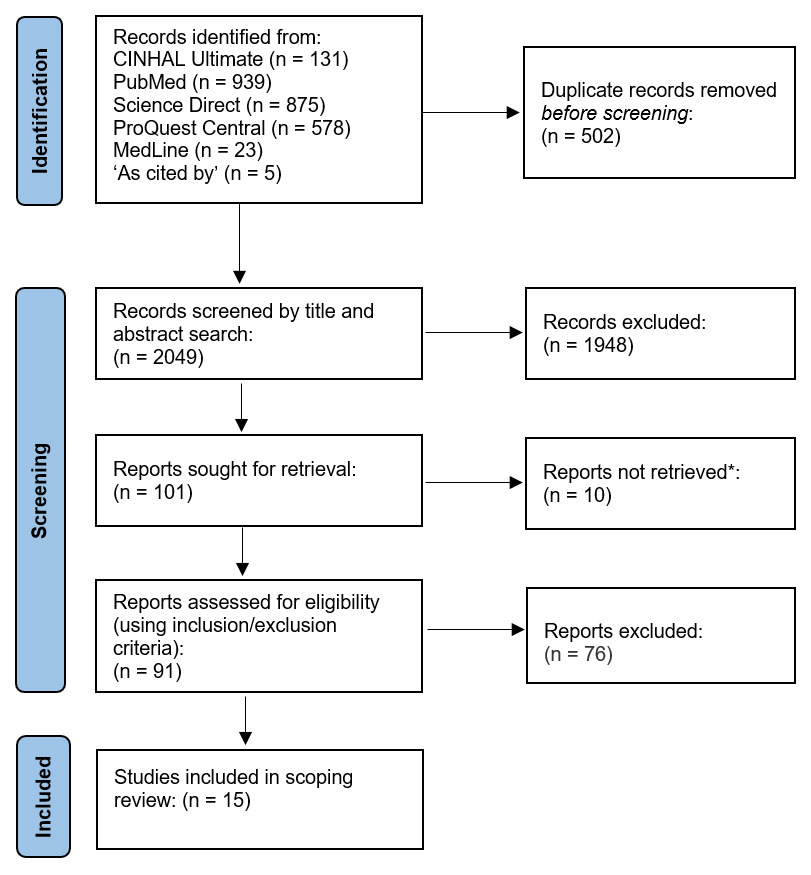

A total of 2,551 articles were identified. Articles were imported into EndNote 20, and duplicates (n=502) were removed. Of the 2409 articles, the title and abstract were read (ML) and included for full-text review if they referred to: patients with historical traumatisation who had engaged in nurse-led TIC and where the priorities of TIC were depicted or expressed. Of the 101 articles, a further 10 articles were not retrieved as were found to meet exclusion criteria. The included articles (n=91) were read in full, with 17 articles deemed to meet the inclusion criteria by the primary researcher (ML) and were submitted to the second reviewer (JB-W) for eligibility assessment. Following the review process, ML and JB-W met and discussed the results. Two articles were excluded as they related to nursing the paediatric population and were determined as irrelevant to the objectives of the scoping review. The final inclusion and exclusion criteria are in Table 2. Fifteen articles were selected for final inclusion. The use of grey literature was a consideration for this scoping review; however, grey literature is beyond the scope of the study due to time constraints and is acknowledged as a limitation. The study selection process was summarised and reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) (Page et al., 2021) (Figure 1). A summary of the final articles, including aims and key findings is provided in the Supplementary File.

SYNTHESIS OF FINDINGS

Objective One: Gaps in literature and future research priorities

Over the past decade, rates of publications demonstrate that TIC in nursing practice is evolving rapidly. A simple PubMed search for (“trauma informed care”) and (nursing) showed an increase in annual publications from 16 in 2015 to 104 in 2024.

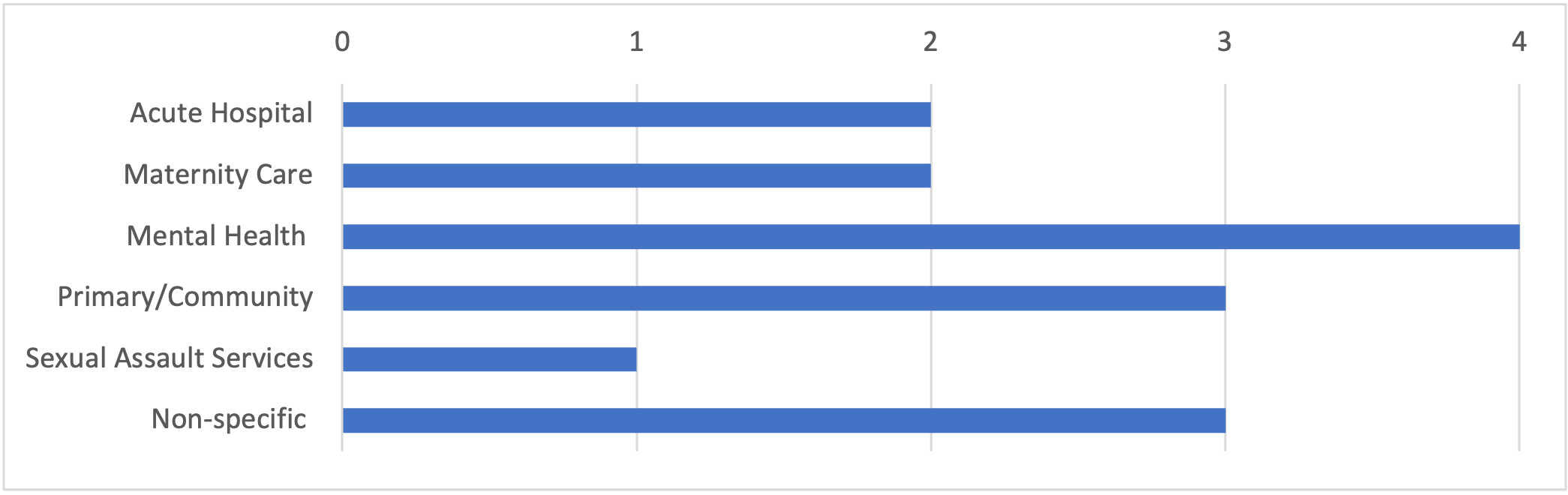

The emergence and representation of TIC implementation across nursing areas was demonstrated through the literature (Figure 2) and included acute hospital care (Bruce et al., 2018; Hall et al., 2016), maternity care (Choi & Seng, 2014; Head & Heck, 2022), mental health care (Muskett, 2014; Stokes et al., 2017; Wilson et al., 2017, 2023), primary/community care (Bergman et al., 2019; Brooks et al., 2018; Varghese & Emerson, 2021), and sexual assault services (Poldon et al., 2021). Three articles were not specific to any particular area of nursing. Reeves (2015) identified TIC literature relevant to women’s health disciplines and a smaller number of theoretical papers in physical therapy, corrections care, orthopaedic care, human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome care, gastroenterology, and oncology; while Guest (2021) acknowledged that TIC is well-integrated in the mental health nursing field. The remaining article (Goddard et al., 2022) focused on TIC as a concept and did not refer to specific areas of nursing practice.

There is a call for universal TIC precautions across all nursing disciplines, which encourages nurses to treat each patient they care for as if they have experienced a traumatic event (Bruce et al., 2018; Goddard et al., 2022; Head & Heck, 2022; Muskett, 2014; Poldon et al., 2021; Stokes et al., 2017; Varghese & Emerson, 2021). Future research should include more diverse participants, areas of nursing care, and survivors of different types of traumatic experiences (Reeves, 2015).

Eight articles originated from the United States of America (USA) (53.3%) (Bergman et al., 2019; Bruce et al., 2018; Choi & Seng, 2014; Goddard et al., 2022; Guest, 2021; Head & Heck, 2022; Reeves, 2015; Varghese & Emerson, 2021). Australian research accounted for five articles (33.3%) (Brooks et al., 2018; Hall et al., 2016; Muskett, 2014; Wilson et al., 2017, 2023). Finally, Canadian-based research was represented in two articles (12.3%) (Poldon et al., 2021; Stokes et al., 2017). However, the search strategy was limited to English language research, hence the origin countries are unsurprising. However, given the prevalence of historical trauma, there is a clear gap in the current mapping of TIC across all fields of nursing and for diverse population groups and Indigenous peoples, providing a direction for future research. There was a demonstrable lack of literature for the Aotearoa New Zealand context.

Objectives two and three: The priorities of nurse-led trauma-informed care and mapping of key research findings

To address objectives two and three, the characteristics of the literature included in this study are presented in tabular format (see Supplementary File). The key findings in the Supplementary File have been explored using the three sub-questions to address objectives two and three. This deductive approach to content analysis is based on preconceived themes that the primary researcher (ML) identified through extensive literature reading, which informed the development of the sub-questions (Daniels, 2018). The key findings in the supplementary table inform the discussion of the three sub-questions and the primary research question: What do nurses need to know about TIC for patients with a history of traumatic experiences?

HOW DOES THE LITERATURE DEFINE TRAUMA-INFORMED CARE?

The concepts of trauma and TIC arising from the literature in this scoping review have been synthesised to define TIC in nursing practice, foundational to answer the question: What do nurses need to know about TIC for patients with a history of traumatic experiences?

Trauma

The historical root of the word trauma is bound to a physical injury commonly associated with soldiers in wartime (Goddard et al., 2022; Guest, 2021). By 1980, the American Psychiatric Association recognised the experience of a significant, tragic event, with subsequent development of mental impairment, for example, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), recognising that the psychological consequences of a traumatic injury may develop and persist long after the physical wounds have healed (Bruce et al., 2018). By the 1990s, trauma was recognised as taking a significant toll on the brain and body, even in the absence of physical injury or harm (Goddard et al., 2022), widening the descriptions to include trauma caused psychologically or emotionally (Bruce et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2017).

Trauma occurs when individuals are unable to prevent, stop or psychologically process an event, overwhelming the person’s coping resources (Brooks et al., 2018; Reeves, 2015). While descriptions of trauma across social service and healthcare disciplines were not always consistent, the SAMHSA (2014) definition was most frequently used within health systems:

Individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life-threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being. (p. 7)

In the reviewed literature, trauma is strongly associated with ACEs, identifying the irrefutable link between childhood exposure to experiences, such as physical and sexual abuse, neglect, and exposure to domestic violence, and adverse health outcomes in adulthood (Bergman et al., 2019; Brooks et al., 2018; Goddard et al., 2022; Guest, 2021; Head & Heck, 2022; Muskett, 2014; Reeves, 2015). Other causes or instigators of trauma among individuals included: physical harm (Brooks et al., 2018; Bruce et al., 2018; Varghese & Emerson, 2021), sexual harm (Bergman et al., 2019; Brooks et al., 2018; Choi & Seng, 2014; Guest, 2021; Head & Heck, 2022; Poldon et al., 2021; Reeves, 2015; Varghese & Emerson, 2021), interpersonal violence (Hall et al., 2016; Reeves, 2015), natural disasters (Brooks et al., 2018; Varghese & Emerson, 2021), war (Brooks et al., 2018; Varghese & Emerson, 2021), or witnessing the harm or death of a loved one (Brooks et al., 2018; Varghese & Emerson, 2021).

Trauma-informed care

In three articles, the authors set out to define the concept of TIC (Goddard et al., 2022; Guest, 2021; Varghese & Emerson, 2021). Facilitating the occurrence of TIC in nursing included: universal precautions of trauma (actual or presumed) and a trauma-informed environment (Goddard et al., 2022); awareness and education of trauma and TIC education and therapeutic skills (Guest, 2021); and trauma competence, health professional readiness, and survivor readiness (Varghese & Emerson, 2021). Staff confidence and competence promoted a culture of TIC (Muskett, 2014). Conversely, a lack of TIC education resulted in providers feeling not proficient, confident, or competent in engaging in TIC (Bergman et al., 2019; Bruce et al., 2018; Choi & Seng, 2014; Hall et al., 2016; Muskett, 2014). Previous background or training, a personal history of sexual trauma, prior exposure to delivering trauma-sensitive care, and a background in rape or crisis counselling were factors that increased the provider’s perceived proficiency to deliver TIC (Bergman et al., 2019).

Concept analysis literature detailed critical attributes of TIC, including trauma awareness, strengths-based, and empathy (Goddard et al., 2022); recognition, knowledge, concern, and respect (Guest, 2021); safety, empowerment, and support in primary healthcare (Varghese & Emerson, 2021). As such, these are related concepts that represent personal and professional qualities demonstrated by the healthcare staff and providers. Brooks et al. (2018) introduced the term ‘holding’ to articulate the provider’s creation of a safe space through TIC skills and empathy. The development of trusted provider-patient relationships may help survivors feel comfortable and empowered to share their stories to work against the power imbalance often reminiscent of abuse (Reeves, 2015). TIC results in empowerment, relationship-building, and resilience in the form of reducing trauma-triggering interactions and environments (Goddard et al., 2022). Similarly, in primary healthcare, Varghese and Emerson (2021) defined TIC as:

A strengths-based approach in which trained, trauma-aware health care professionals provide services that prioritise safety, empowerment, and support, resulting in improved patient satisfaction and healthcare engagement in individuals who have experienced trauma. (p. 465)

What are nurses’ views and experiences of trauma-informed care?

The value of implementing TIC was evident across the literature, with nurses mostly holding favourable opinions about incorporating TIC into their practice (Bruce et al., 2018). Stokes et al. (2017) recognised that while the connection between the value of TIC and provider competence is critical, some TIC principles are closely connected to the fundamentals of nursing, the importance of patient-centred approaches, and the centrality of the therapeutic relationship. Nurses have professional, ethical, and moral duties to tailor care to patients’ needs, including trauma (Head & Heck, 2022).

A lack of understanding and confusion of the concept of TIC in practice was a barrier to implementation (Bruce et al., 2018). Nurses reported that their knowledge and education influenced the implementation of TIC in their practice and identified these as a specific need, including in undergraduate nursing education (Bruce et al., 2018; Choi & Seng, 2014; Hall et al., 2016; Poldon et al., 2021). The positive impact of TIC education for nurses, which included their ability to explain TIC, translated into attitudinal shifts and improved patient-provider interactions (Hall et al., 2016). Integrating knowledge of trauma and TIC into existing nursing curricula on theoretical and practical levels is necessary (Stokes et al., 2017) and requires further research.

The nurse’s awareness of trauma in an individual was a theme throughout the literature, including recognising the impact of trauma on health (Brooks et al., 2018; Bruce et al., 2018; Choi & Seng, 2014; Poldon et al., 2021; Reeves, 2015); identifying the consequences of trauma in consultations (Bergman et al., 2019; Brooks et al., 2018); and screening for trauma among patients (Choi & Seng, 2014; Head & Heck, 2022; Muskett, 2014; Reeves, 2015). By reassuring patients, health professionals can foster a deeper, more holistic understanding of their experiences. However, a lack of clarity of the TIC approach by the healthcare team, contributed to confusion and misunderstanding for patients, potentially leading to suboptimal care (Poldon et al., 2021).

The lack of time was a significant obstacle in nurses’ experiences of providing TIC (Bergman et al., 2019; Brooks et al., 2018; Bruce et al., 2018; Hall et al., 2016; Reeves, 2015; Stokes et al., 2017). The reasons given included: the extra time required to conduct physical examinations, gender-specific examinations, leaving space for patients to bring up their trauma history, time to engage in the relationship, trust-building between patient and provider (Bergman et al., 2019); and rapid turnover and complex presentations in the emergency setting (Hall et al., 2016). Restrictions in consultation time in primary healthcare hindered TIC practice (Reeves, 2015).

The quality and effectiveness of TIC depends highly on the relational dynamic between the nurse and the patient (Muskett, 2014). Improving the nurse-patient relationship in TIC requires creating a safe space (Brooks et al., 2018) to provide safe long-term relationships with staff, minimising distress (Brooks et al., 2018; Head & Heck, 2022; Muskett, 2014; Poldon et al., 2021; Reeves, 2015), where client’s are fully informed and empowered to have control over their own care (Brooks et al., 2018; Choi & Seng, 2014; Reeves, 2015; Stokes et al., 2017; Wilson et al., 2017). However, the difficulties of fostering a therapeutic patient-nurse relationship were documented in eight articles (Bergman et al., 2019; Muskett, 2014; Poldon et al., 2021; Reeves, 2015; Stokes et al., 2017; Varghese & Emerson, 2021; Wilson et al., 2017, 2023). Individual recounts of trauma can complicate the nurse-patient relationship, including re-traumatisation for patients (Stokes et al., 2017).

The literature clearly identified the negative impact on nurses engaging in TIC. Those who frequently worked with patients who have experienced trauma may experience vicarious trauma and burnout, and further, those who have experienced trauma may find themselves re-traumatised (Brooks et al., 2018; Choi & Seng, 2014; Guest, 2021; Poldon et al., 2021; Stokes et al., 2017; Varghese & Emerson, 2021; Wilson et al., 2023). Protective strategies revolved around individual and team self-reflection (Stokes et al., 2017). For nurses who provide TIC to survivors of sexual violence, Poldon et al. (2021) called for managers to provide education and support to develop resilience to protect against vicarious trauma. The importance of leadership to create an organisational culture to successfully engage with TIC values is critical (Varghese & Emerson, 2021). This includes committed leadership advocating for TIC, champions, team buy-in, and ongoing evaluation (Muskett, 2014; Poldon et al., 2021; Stokes et al., 2017; Varghese & Emerson, 2021).

Finally, the immense value of supportive peers and colleagues, specifically related to emotional support and assistance in caring for patients with complex needs, was evident (Poldon et al., 2021). However, 25% of nurses included in their study did not have a colleague they could turn to for assistance with patients experiencing stress or trauma (Bruce et al., 2018) and others were unsure which colleagues might support them (Hall et al., 2016). The value of a team leader who guides their colleagues through relational dynamics and creates a sense of safety within the caring space was valued (Wilson et al., 2023). While Choi & Seng (2014) referred to nurses finding the delivery of TIC rewarding and Poldon (2021) referenced nurses finding comfort in practicing TIC, there was limited evidence in this space. Further, none of the literature explored the perceived benefit of supportive co-workers and management to TIC and the relevance of professional supervision, indicating areas for future research.

What TIC practices can nurses use to support patients?

Trauma-informed care needs to be distinguished from recovery or person-centred care, where to provide effective TIC requires staff to recognise and comprehend the link between childhood trauma and adult psychopathology (Wilson et al., 2017). By linking the concept of TIC to the basic philosophy of nursing care, with the understanding that trauma impacts the patient’s holistic well-being, nurses may feel more confident to engage in TIC regardless of the nursing setting. Further research is required to support nurses to apply TIC to their practice successfully (Poldon et al., 2021).

The importance of trauma screening was acknowledged by nurses (Bruce et al., 2018; Choi & Seng, 2014; Goddard et al., 2022; Head & Heck, 2022; Muskett, 2014; Reeves, 2015; Varghese & Emerson, 2021). Muskett (2014) suggested screening for trauma at the point of admission to identify the patient’s trauma history was the first step to TIC. However, given trauma has complex effects on holistic well-being, learning how and when to screen was an essential priority for nurses (Choi & Seng, 2014). In the main, nurses do not routinely ask patients whether they have experienced traumatic life events (Reeves, 2015).

The consultation or interview process between patient and nurse requires strategies that many would consider the essential ingredients of contemporary, effective mental healthcare (Muskett, 2014). Having the flexibility to adapt consultation length (Brooks et al., 2018) to enable time to identify patient’s experience of distress and inviting trauma disclosure (Bruce et al., 2018; Choi & Seng, 2014; Head & Heck, 2022) are necessary skills; together with recognising behavioural cues of potential child sexual abuse or other trauma during interviews and clinical assessments (Bergman et al., 2019; Head & Heck, 2022; Reeves, 2015). Importantly, is the need to avoid victim blaming and making assumptions, accommodate client preferences to enable control, and accept that there may not be an ‘easy fix’ to a history of trauma (Choi & Seng, 2014).

To ensure a safe physical environment, assessments should be conducted in a private, comforting environment to mitigate re-traumatisation risk, assuring confidentiality and privacy with a support person present, if required (Brooks et al., 2018; Head & Heck, 2022; Varghese & Emerson, 2021). Alternative spaces are necessary to enhance patient safety, comfort and self-esteem, and defuse distress, regardless of the space created for TIC practice (Muskett, 2014). For example, the physical space and environment in an acute mental health unit may re-traumatise a patient, affecting patient experiences of safety and jeopardising the therapeutic relationship between nurse and patient (Wilson et al., 2023). To ensure TIC practice environments are welcoming, changes may include painting walls with warm and soothing colours (Muskett, 2014; Varghese & Emerson, 2021; Wilson et al., 2017); providing comfortable seating areas and furnishings, rugs, and indoor plants (Muskett, 2014; Varghese & Emerson, 2021; Wilson et al., 2017); art and craft contributions, calming music, and the use of pleasant smells (Muskett, 2014).

Strengths-based care encourages patients to acknowledge their strengths, identify resources, emphasise adaptations, and celebrate their successes (Brooks et al., 2018; Varghese & Emerson, 2021). Identifying existing positive supports (family, friends, spiritual) is crucial in TIC, to identify skills and knowledge they already embody for repairing and strengthening relationships, meeting safety needs, and achieving a sense of belonging (Varghese & Emerson, 2021). Nursing strengths-based actions in TIC aim to empower and build resilience and promote healing (Goddard et al., 2022; Poldon et al., 2021).

Limitations

While a limitation of scoping review methodology is the possibility that relevant literature may have been missed (Pham et al., 2014), the intention is not to be exhaustive but to explore the breadth of the available evidence for a particular topic or concept (Osorio et al., 2025), in this case to update the understanding of TIC in relation to the practice of nursing. Definitive practice recommendations cannot be made as critical appraisal of the articles is not assessed (Pham et al., 2014), instead, findings may be diverse and varied (Osorio et al., 2025). Including grey literature was beyond the scope of the study due to time constraints and is a limitation. Finally, the term ‘abuse’ was not used as a lone search term, which may have led to missed evidence. A widening of the search terms and inclusion of grey literature are suggestions for future research.

Implications for nursing and future research

Over the past decade, there has been considerable growth in TIC research in nursing, with recommendations that the principles of TIC provide a framework to improve patient-centred, holistic nursing care that values emotional space for safety, transparency, collaboration, and hope (Archer-Nanda & Dwyer, 2024). TIC requires knowledge of the impacts of intersectionality (gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity, age, socioeconomic status, (dis)ability) on trauma to promote equity (Klein et al., 2024; Toste et al., 2025). The recent Abuse in Care Royal Commission of Inquiry (2024) in Aotearoa New Zealand was followed by an apology from the Nursing Council of New Zealand (2025) stating a commitment to embed TIC into nursing education. However, there is a lack of evidence on how to implement TIC into practice. Future research needs to focus on trauma screening processes, including identifying enablers and barriers, and ensuring appropriate TIC can be enacted across diverse clinical settings.

Research published since the literature search for this review was completed, echoes the call for TIC curricula in nursing education and professional development, with significant potential for enhancing care quality and fostering a trauma-informed healthcare system (Hamby, 2025; Qin et al., 2025; Young et al., 2025). While principles of TIC relate to many concepts in nursing care, such as building safe therapeutic relationships, further knowledge and skills are required to improve understanding of TIC, behavioural cues, impact of childhood trauma, and assessment techniques. Identifying retraumatising triggers and creating safe spaces for patients to share their experiences is central to education and improving healthcare environments. Developing and delivering education and implementing TIC in practice requires research.

This scoping review included literature from the USA, Australia, and Canada, indicating a gap in research in Aotearoa New Zealand. Pihama et al. (2020) undertook a project ‘He Oranga Ngākau: Māori approaches to Trauma Informed Care’, which has provided evidence to support Māori providers, and Māori and non-Māori counsellors, clinicians and healers, to explore TIC and how to deliver this in practice using kaupapa Māori principles. Malone & Bingham (2024) undertook a small study in Aotearoa New Zealand, delivering an eight-week online course on TIC to healthcare professionals, including nurses, and recommended mandatory micro-credentialling in TIC for nurses. Given the context of nursing in Aotearoa New Zealand being underpinned by cultural safety with a commitment to Te Tiriti o Waitangi and equity for Māori (Wepa, 2015), exploring how TIC can be delivered in a way that is culturally safe and responds to collective (and not only individual) trauma is essential.

Finally, the impact of working with individuals and communities who have experienced trauma requires managerial support, committed leadership, and peer support to foster a TIC culture in nursing. Opportunities for self-care and self-reflection individually and within teams is critical. Implementation of TIC must be evaluated to include the effects on staff to prevent vicarious trauma and burnout. Evidence is required to highlight strategies for ensuring the health and wellbeing of healthcare professionals as well as identifying the value and job satisfaction of working using a TIC approach.

CONCLUSION

This review has summarised and mapped the relevant literature regarding TIC and suggests future directions for research. The concept and implementation of nurse-led TIC requires clarification across the nursing sector. However, nurses recognise the value of TIC and the impacts of positive therapeutic relationships, including the basic tenets of nursing care and TIC knowledge, to avoid patient re-traumatisation in the healthcare setting. There is a broad scope for future research: clarification of the concept of TIC and implementation into practice; patient screening and assessment; TIC education and practice for healthcare professionals, particularly in the Aotearoa New Zealand context; identifying key strategies within healthcare organisations and settings to deliver TIC that promotes health equity and ensures the wellbeing of healthcare professionals.

Funding

This scoping review was undertaken as part of a Master of Health Practice at Ara Institute of Canterbury. The master’s programme was partially funded by Te Whatu Ora Postgraduate Nursing Education Fund – Waitaha Canterbury, with thanks.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Acknowledgments

This scoping review is dedicated to the courageous individuals who continue to enter healthcare systems despite their history of trauma – thank you for your self-expression, your bravery, and your vulnerability. I hope, one day soon, we will consistently care for you in a way that does not cause further harm.

To the nurses who continue to challenge practice, shift attitudes, and adapt policy, thank you for seeing and honouring your patients. You are participating in a beautiful movement.

To Dr. Rea Daellenbach, thank you for your encouragement and support. I am grateful.

To Dr Sue Adams, for proofreading and editing this article. Thank you for your guidance.