INTRODUCTION

Healthcare has experienced accelerated growth in the use of digital technologies (Jones et al., 2019) and this comes with the need for the healthcare workforce to adopt and utilise such technologies in practice. Nurses are recognised as a major and essential component of the health workforce (World Health Organization, 2021). Therefore, nurse leaders have a vital role in supporting nurses to adopt digital health.

Nurses’ engagement with digital health

The World Health Organization (WHO) describe digital health as the utilisation of digital, mobile, wireless, and information and communications technologies to facilitate the accomplishment of health goals (World Health Organization, 2016). Internationally, more nurses are accessing data, entering clinical records electronically and delivering care using clinical and telehealth applications (Skiba, 2017). The importance of digital health and delivering nursing care remotely has been spotlighted with the COVID-19 pandemic (Nazeha et al., 2020). Examples of national digital health applications used by nurses include interRAI (InterRAI New Zealand, n.d.); TrendCare, a patient acuity tool used to inform the Care Capacity Demand Management (CCDM) programme (O’Connor, 2016); and the National Immunisation Register (Ministry of Health, 2021). The growth in digital health and data collection however, also generates ethical, security, privacy and confidentiality risks that nurses need to be aware of when using any technology (Dobson et al., 2022). Indeed, recent examples in Aotearoa New Zealand, such as inappropriate viewing of medical images and cyber hacking in public hospitals and primary health organisations have recently been publicised (Dobson et al., 2022).

Digital literacy is seen as a core requirement in contemporary health and clinical education (Kennedy & Yaldren, 2017). While approximately three quarters of nurses feel they are digitally literate and competent (Kuek & Hakkennes, 2020), many digital health initiatives fail due to lack of uptake and engagement from users (Brown et al., 2020). Nurses may disengage when faced with technical issues; poor software and computer hardware usability and access; disrupted workflows; decreased interpersonal communication; poor access to training; lack of management support and communication; increased pressure due to lack of time and cost constraints; or when nursing’s voice is not evident in the system design and implementation (Brown et al., 2020; Strudwick et al., 2019; Surani et al., 2019; Walker & Clendon, 2016). Gaining nurses’ engagement is key to ensuring successful implementation and use of digital health solutions and it has been suggested strong leadership is key (Kennedy & Yaldren, 2017).

Leadership and digital health

Successful implementation of digital health requires good leadership, as well as the right policies, technology, infrastructure and financial resources (Desveaux et al., 2019). Poor leadership, or a lack of leadership, has been associated with failed implementation and poor uptake of digital health (Laukka et al., 2020). Digital leadership in nursing is yet to be explored in depth, and the few studies found focus mainly on high-level strategic, executive and management nursing roles (Remus, 2016; Strudwick et al., 2019). However, nursing leadership can be exercised by nurses at all levels, as leadership is a core function of nurses’ clinical practice and not solely the remit of nurse managers and executives (Curtis et al., 2011). For instance, nursing leader roles such as champions, have been acknowledged as enablers for the implementation and ongoing support for digital health (Gui et al., 2020). Understanding how nurse leaders can enable nurses to engage in digital health is the focus of this integrated literature review.

METHODS

Integrative literature reviews enable a broad approach to sampling literature, critiquing, summarising and synthesising research in order to draw holistic conclusions on a topic (Toronto, 2020). This integrative literature review followed the six-stage process described by Toronto (2020). The first stage, problem identification, led to the research question: How do nursing leaders enable hospital nurses to adopt and use digital health technology? Stage two is the search strategy which was informed by the research question. Between September and October 2020, a comprehensive search of the literature was conducted, and this was updated in February 2022. Three electronic databases were accessed: CINAHL, MEDLINE and EMBASE. In addition, Google Scholar was used to complement the database search. The following limitations were applied: English language, and only literature from 2015 onwards, due to the pace of digital technological advances.

The research question led to four key concepts: nurse, leadership, digital health, and hospital setting. The use of truncation enabled all forms of a word to be considered to broaden the capture of citations (Toronto, 2020). Keywords were then combined using Boolean logic (Lawless & Foster, 2020). Table 1 provides an overview of terms and Boolean logic combinations.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria further focused the search. Studies were considered if the population comprised registered nurses, enrolled nurses or nurse practitioners, to capture the breadth of qualified nurses. Student nurses were excluded. The setting was limited to acute care settings and excluded primary health settings. Primary research and verified expert opinions were included, however, opinion and editorial columns were excluded. Finally, studies had to be focused on nurses rather than service users or patients.

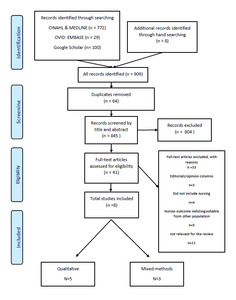

The database searches identified 801 citations. Google Scholar produced over 17000 results therefore only the first 100 results, with the sort by relevance function active, were considered. Hand searching through reference lists from grey literature resulted in another eight citations for consideration. With all citations 909 articles were identified. Removal of duplicates (n=64) left 845 studies that were first screened by title and abstract, then by full text, for relevancy. The final number of studies included for quality appraisal was eight. Of these, five papers were qualitative primary research and three studies used mixed methods. Figure 1 provides a flowchart based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline (Moher et al., 2009) summarising the selection of studies.

For stage three, the appraisal of quality was conducted using the John Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Model (JHNEBP) appraisal tools (Dang & Dearholt, 2017). A summary of all studies and their quality appraisal ratings is presented in Table 2.

In stage four of the integrative review, analysis was performed using the content analysis process described by Erlingsson and Brysiewicz (2017) where data was extracted and condensed into meaning units, then interpreted and labelled into codes, which were then clustered into patterns of similarity and emergent categories became apparent. Finally, categories were aligned to identify key themes. This process identified three themes: connecting the digital and clinical worlds; facilitating digital practice development; and empowering nurses in the digital health world (Table 3). Stage five is the discussion and conclusion, where the results are compared and contrasted with other literature; and stage six is dissemination, sharing the synthesis within professional communities (Toronto, 2020).

RESULTS

Each of the three themes, with their associated sub themes (Table 3) are now described.

Theme One: Connecting the digital and clinical worlds

Enabling integration into clinical practice

This review found nurse leaders need to create links between the clinical and digital domains in healthcare to facilitate integration of digital tools into nursing practice. Understanding the impact of digitisation on nurses’ workload and workflow enables nurse leaders to better support staff. Nurses’ expressed dissatisfaction when they felt that workflows following digital implementation did not reflect the realities of their clinical practice (Bail et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2015; Zadvinskis et al., 2018). A disconnect between clinical and digital implementation priorities seemed to occur in two situations; either when trainers and support staff had non-clinical backgrounds and focus more on system design whilst paying little attention to nurses’ workflow; or when management was perceived as unable or unwilling to understand the realities of nursing workflow (Bail et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2015; Zadvinskis et al., 2018). When new digital ways of working are introduced without withdrawing redundant requirements, nurses can feel this adds and complicates their work, making adoption of new technology challenging (Zadvinskis et al., 2018). This is particularly exacerbated when staffing levels are inadequate (Varsi et al., 2015). To support implementation and integration of digital health, nurse leaders can proactively schedule replacement staff, ensure clinical units are adequately staffed and that nurses are backfilled when sent away for digital health training (Strudwick et al., 2019), which supports adjustment to fluctuations in workload (Varsi et al., 2015). In addition, nurses report that a reduction in patient allocation is an enabler to adoption during the implementation phase (Zadvinskis et al., 2018). If mitigation and support plans are not considered when digital solutions are being implemented and nurse leaders are not aware of the impact on nursing workflow, conflict can ensue between the priorities of clinicians and management, leading to the implementation and integration of digital solutions being compromised (Bail et al., 2020; Zadvinskis et al., 2018).

Leadership visibility in clinical practice

Nurse leaders’ presence in clinical settings encouraged frontline nurses to use digital health tools, and nurses valued leadership feedback on their performance (Strudwick et al., 2019; Yuan et al., 2015). Conversely, the absence of nurse leaders led to some nurses perceiving this as a lack of support for the digital implementation, resulting in them feeling demotivated (Bail et al., 2020). Although the use of electronic communication to keep nurses informed was seen as useful, frontline nurses report preference for in-person team huddles facilitated by nurse leaders to enable a responsive forum to express concerns and resolve issues (Strudwick et al., 2019).

Digital credibility

Nurse leaders who role-model, are technologically competent and directly assist with technical issues display digital credibility (Strudwick et al., 2019; Yuan et al., 2015). Additionally, nurse leaders who demonstrate technological competence gained credibility with nurses, positively influenced their adoption of digital health (Konttila et al., 2019). Indeed, nurses feel supported and motivated to use new technology when surrounded by digitally savvy leaders (De Leeuw et al., 2020).

Theme two: Facilitating digital practice development

Digital coaching by champions

Nurse leaders can be enablers of digital practice development through supporting digital coaching, ensuring access to training and education, and enabling a learning culture. Nurse leaders with digital knowledge and experience can directly provide coaching through giving demonstrations and feedback (Strudwick et al., 2019). However, the ability to provide direct support can be hindered by competing priorities, particularly for nurse leaders with formal management responsibilities (Strudwick et al., 2019). In this situation supporting the development of digital nursing practice may be better served by dedicated champions, sometimes also referred to as super users or digital coaches (Yuan et al., 2015), as these nurses may be in a better position to support, without the distractions of management responsibilities (De Leeuw et al., 2020; Strudwick et al., 2019). Nurse leaders can foster a peer support culture by ensuring new employees receive practical support from nurse-champions who are already well integrated in the workplace and who can act as digital role-models and coaches (Varsi et al., 2015). Nurses report that having regular access to champions reduces their pressure and stress (Yuan et al., 2015; Zadvinskis et al., 2018). Nurses challenged by digital change found their digital development was better when nurse leaders provided access to champions who proactively support continuous learning (De Leeuw et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2015; Zadvinskis et al., 2018).

Access to training and education

Access to education and training is imperative for integrating use of digital health into clinical practice and nurse leaders need to commit to ensuring education is accessible to nurses (Konttila et al., 2019; Strudwick et al., 2019). Sustaining appropriate and successful use of digital health requires regular mandatory education updates combined with optional workshops (Konttila et al., 2019; Strudwick et al., 2019). Nurse leaders who promote a co-design approach to learning with nurses and enable access to on-demand learning, such as e-learning and webinars, enhance staff development opportunities (De Leeuw et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2015). Conversely, poorly planned education can lead to training that is: not meeting learners’ needs; delivered too early pre-implementation; rushed, fast and overwhelming; too involved and comprehensive; or too time consuming, all of which can negatively impact frontline nurses (De Leeuw et al., 2020; Konttila et al., 2019; Varsi et al., 2015; Yuan et al., 2015; Zadvinskis et al., 2018).

Enabling a learning culture

By integrating learning opportunities into daily work and providing sufficient time and resources, nurse leaders generate a supportive learning culture (De Leeuw et al., 2020; Konttila et al., 2019). Nursing leaders can create a digital play environment where, in combination with learning on the job and support from digitally knowledgeable colleagues, nurses explore new ways of working, which can be helpful and motivating (De Leeuw et al., 2020; Konttila et al., 2019).

Theme three: Empowering nurses in the digital health world

Leader as advocate: hearing the nurses’ voice

To fully engage and adopt digital health nurses need to be empowered to make active contributions to the design and implementation of digital solutions which nurse leaders can support by advocating and ensuring nurses’ ideas and concerns are heard. By collecting frontline nurses’ feedback and suggestions, then relaying this information to operational and information technology managers, nurse leaders ensure the voice of frontline nurses is heard (Strudwick et al., 2019; Varsi et al., 2015). When nurses contribute earlier, in implementation phases, designers of digital solutions can better prioritise and respond to their needs (Bail et al., 2020). Furthermore, making nursing feedback a regular agenda item in management meetings allows nurse leaders to bring a nursing voice to other leaders within an organisation and raise visibility of issues and solutions suggested by frontline nurses (Gephart et al., 2015; Strudwick et al., 2019; Varsi et al., 2015; Zadvinskis et al., 2018). Nurses are reported to feel disempowered when not listened to or not provided with opportunities to actively participate in decision-making related to the design and implementation of digital technologies (Bail et al., 2020; Gephart et al., 2015). Nurses could provide input on training material content, suggest workflow redesign and advise on modifications to digital tools (De Leeuw et al., 2020; Gephart et al., 2015; Zadvinskis et al., 2018).

Enabling leadership behaviours and attributes

The literature identifies leadership behaviours and attributes that best enable frontline nurses to engage with digital health. For instance, nurse leaders who have digital implementation experience are more likely to be aware and sensitive to the challenges faced by nurses who are less technologically competent (Strudwick et al., 2019). By showing empathy to nurses who are adjusting to using digital health tools, nurse leaders can enhance engagement with digital skills development (De Leeuw et al., 2020; Strudwick et al., 2019). Other behaviours that enhance uptake of digital health include offering assistance, positive communication, actively supporting, providing resources, being available, rewarding good practice, and role-modelling proactive behaviours (De Leeuw et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2015; Zadvinskis et al., 2018). Conversely, nurse leaders who excessively use digital health jargon and neutral or negative communication, can alienate nurses which can have a negative impact on collegiality and cohesion, as it can generate feelings of incompetency for those less digitally confident (De Leeuw et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2015).

Workplace culture

Workplace culture impacts every aspect of using digital technologies, however, is most evident during implementation. A positive workplace culture is enhanced when highly engaged nurse leaders articulate a clear vision, goals, purpose, and rationale for digital implementation (Konttila et al., 2019; Yuan et al., 2015). Negative attitudes and unsupportive organisational cultures discourage nurses from adopting and using digital health solutions (Bail et al., 2020; Konttila et al., 2019). If the workplace and organisational culture is risk averse, imposing for example, a status quo attitude of replicating paper forms in digital solutions, nurses may become reluctant to engage, not because they are resistant to change, but because they perceive the digital system as having diminished utility (Bail et al., 2020). Alternatively, nurse leaders who create a positive workplace and implementation climate that is supportive of change and innovation, in conjunction with the provision of adequate resources such as time, training opportunities, appropriate equipment and guidance in practice, best supports frontline nurses (Gephart et al., 2015; Varsi et al., 2015; Yuan et al., 2015). This leads nurses to propose new ideas and make suggestions for improvements which increases their engagement (Gephart et al., 2015; Varsi et al., 2015; Yuan et al., 2015). Furthermore, a positive team culture based on collegial learning and support, where nurse leaders emphasise the importance of helping each other, can result in reduced stress for nurses lagging and feeling less confident with digital implementation (De Leeuw et al., 2020; Zadvinskis et al., 2018).

DISCUSSION

The findings from this review suggest nurse leaders need to create a link between clinical and digital worlds to facilitate integration of digital tools into practice. Nurse leaders’ presence, and their ability to act as mediators between digital health implementation priorities and clinical workflow realities, are key (Surani et al., 2019; Umstead et al., 2021). This is because nurse leaders can intervene and reduce unintended consequences, such as disrupted workflows, that may compromise use of digital solutions (Umstead et al., 2021).

Additionally, this review found that nurse leaders require digital competence to have digital credibility so they can share their knowledge, provide technical support, and coach nurses to resolve technical issues, which in turn may increase nurses’ motivation with adoption of digital tools. The importance of digital competence in nurse leaders has been highlighted in prior research (Adeleke et al., 2015; Sharpp et al., 2019). Likewise, nurse leaders’ gaps in digital knowledge and skills can create barriers in their ability to effectively support digital implementation (Adeleke et al., 2015; Sharpp et al., 2019). This is echoed by Laukka et al. (2020), who have linked nurse leaders’ technical expertise to their ability to support staff with integrating digital health in practice. However, it is also noted that some nurse leaders may require support to develop digital competencies (Collins et al., 2017). One option is for nurse leaders to use a champion to enhance the use of digital tools, which is a recognised strategy (Gui et al., 2020; Laukka et al., 2020).

Nurses require further education to improve their digital knowledge and skills to support their use of digital technologies (Brown et al., 2020; Kennedy & Yaldren, 2017; Skiba, 2017). This review’s findings suggest that nurse leaders can actively support education, affirming other research describing how nurse leaders need to enable nurses to access education to facilitate the adoption of digital health (Staggers et al., 2018). Research also suggests that after initial education, nurse leaders must enable continuing education so nurses maintain and refresh their digital skills (Brown et al., 2020). For this to occur, the findings of this review indicate nurse leaders need to provide nurses with protected release time from clinical duties to attend training, best achieved by adapting rosters, sourcing staffing resource to backfill clinical rosters, and allowing flexible scheduling. This aligns with research confirming that when nurse leaders take responsibility for the provision of education, a shift in attitude towards adopting digital technology ensues (Brown et al., 2020; Laukka et al., 2020).

Regular communication during digital implementation is essential, but this alone may not be sufficient. Indeed, research suggests that pre-implementation communication from nurse leaders is also needed to underscore potential changes and to enhance nurses’ readiness for digital health (Hansen et al., 2019). This review highlights communication from nurse leaders relaying frontline nurses’ feedback is key for ensuring their voice is heard in the decision-making and implementation phases of digital health, which is supported by literature (Staggers et al., 2018; Surani et al., 2019).

The leadership traits noted include demonstrating positive, empowering and proactive behaviours, such as showing empathy for nurses challenged by technology; being supportive and accessible; acknowledging and rewarding good practice; and role-modelling use of digital tools. Such leadership traits are relational in nature, and relationally focused leadership styles have been associated with improved teamwork, collaboration and nurse empowerment (Cardiff et al., 2018). Furthermore, the leadership traits described resonate with some of the key principles of transformative leadership, which is characterised as a leadership style that stimulates, motivates, inspires, and develops potential in others through a vision, to bring transformation in attitudes, behaviour and belief in order to facilitate change and innovation (Laukka et al., 2020; Remus, 2016). Exploring the links between transformational nursing leadership and digital health is an area for future research.

Limitations of this review include the search strategy as only eight studies were identified, which may be due to restricting the search to articles from 2015. However, recent thinking related to nursing leadership and digital health were sought. Another limitation may be the population of nurses in acute care environments. Including community-based nurses may have added further studies and this should be considered as an area for further research. In addition, nurse leaders may not have the term ‘nurse’ in their job title and this key term may have limited the search. Finally, as the majority of the eight selected studies were conducted in North America, Europe and Australia, the results may not be applicable to Aotearoa New Zealand, as specific cultural considerations, both from a societal and a professional nursing perspective, are not taken into account. Finally, the changing nature of digital health means this study should be repeated within five years.

CONCLUSION

Nurses are the majority workforce in healthcare, therefore need to be empowered and recognised as key stakeholders in the digital transformation of healthcare. This integrative review highlights that nurse leaders create a link between clinical and digital worlds to enable the integration of digital technology into nurses’ practice. The findings show that nurse leaders support nurses through digital transformation by themselves having digital competence and contemporary knowledge; being present and visible in clinical practice; driving and informing education and digital practice development; advocating for and empowering nurses; and displaying positive and visionary leadership traits. Transformational leadership and dedicated champions can support nurse leaders to facilitate the connection between nursing and digital health.

Funding

None

Conflicts of interest

None