INTRODUCTION

Stroke is still the world’s second-leading cause of death and the third-leading cause of mortality and disability (Owolabi et al., 2022). For three decades (1990-2019), stroke has been a significant global burden in terms of incidence, deaths, prevalence, and disability-adjusted life years (Feigin et al., 2021). The World Stroke Organisation Global Stroke Fact Sheet 2022 reports that stroke incidence for women (6.4 million) exceeded that of men (5.8 million), similar to the trends in stroke prevalence between women (56.4 million) and men (45.0 million), with most of these people residing in low to middle-income countries (Feigin et al., 2022). A meta-analysis of 13 high-quality stroke studies confirmed that women consistently experience more significant long-term mortality than males following stroke (Phan et al., 2019). Also, the United States (US) National Vital Statistics Reports 2019 reported that stroke is the third leading cause of death in women, whereas it is the fifth in males (Heron, 2021). Therefore, understanding women’s stroke experience, and focusing on their perceived burdens and support needs is vital, as this may lead to future stroke management guidelines and better after-stroke care strategies.

Recent statistics show that the incidence of any stroke in the young adult has increased by twenty three percent in the last decade, contrasting with rates in older adults, which have decreased 11% (Ekker & de Leeuw, 2020). A US study found that before 44 years of age, women had a higher stroke incidence than men (Leppert et al., 2020). This aligns with a Netherlands study that found that women between 18 and 44 years old have more strokes than males (Ekker et al., 2019). Moreover, in Canada, stroke incidence in women under 30 is increased compared to men (Vyas et al., 2021). Young women who survive stroke have worse outcomes, with a two to a threefold higher risk of poor functional effects than men (Synhaeve et al., 2016).

Meta-analyses described women are disproportionately impacted by stroke due to female-specific risk factors, are more disabled, and have poorer quality of life (Taft et al., 2021). Recent studies examined how sex differences in stroke affect different aspects, including physical and psychological effects. Examples include physical dependency on activities of daily living (Liljehult et al., 2021; Synhaeve et al., 2016), depression (Gall et al., 2018; Mayman et al., 2021), and cost of care provision (Qureshi et al., 2022; Yu et al., 2021).

New Zealand as context for this study

The context of this study is Aotearoa New Zealand, where stroke is the second leading cause of significant adult disability and death. The annual incidence of stroke in Aotearoa New Zealand is 9,500 cases, with an estimated 2,000 deaths annually (New Zealand Stroke Foundation, 2021) and has the second highest age-adjusted incidence rate among developed countries (Leppert et al., 2020). According to a 2020 report, about one-third of strokes occur in younger people, those under 65 (New Zealand Stroke Foundation, 2020). A stroke prevention and management focus is critical because 66% of the population is 15-64 years old. In addition, the mortality due to cerebrovascular disease is higher among women (61%) than men (39%), with ischaemic stroke being the most common type of stroke (New Zealand Stroke Foundation, 2020). In particular, there are ethnic disparities in Aotearoa New Zealand. Māori and Pacific people are substantially more likely than people of European ethnicity to have a stroke throughout their working lifetimes and this has not changed over the last few decades (Thompson et al., 2022).

Public and private organisations in Aotearoa New Zealand offer various services, including educational websites, peer support groups, telephone support, counselling, and in-home support to women and families (Health Navigator New Zealand, 2023; Pearson et al., 2020). Comprehensive stroke care strategies are needed for women to reduce stroke incidence, minimise complications, and manage the complex burdens they may experience (Boehme et al., 2021; Taft et al., 2021). Stroke care strategies specifically designed for women are more likely to be effective if they reflect the experiences of women who have survived stroke, hence this study aims to explore the experiences of younger women who have survived stroke.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This study uses the qualitative description approach developed by Sandelowski (2000). Focus group discussion was selected for data collection. This method supports exploring experiences, thoughts, and ideas about specific topics, and the group interactions can encourage participants to elaborate on ideas; hence, there is the potential to get more information (Plummer, 2017). Eligible focus group participants consisted of women (who agreed to participate) with a past or current stroke diagnosis, and who were aged 18 to 64 years when they experienced their stroke. The focus group interview was held at a convenient time and location for participants, and all were offered the opportunity to join in person or via videoconferencing (Zoom).

The principal investigator accessed existing stroke community networks and an email invitation to participate was distributed. This study used a snowball recruitment method, where those who received the email were asked to forward the message on to others who might wish to participate (Whitehead et al., 2020). Five women who had experienced a stroke and were eligible, agreed to join one focus group interview. This study received ethical approval from the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (Ref: 024663). The focus group interview was recorded and transcribed verbatim. Thematic analysis was undertaken following the steps described by Braun and Clarke (2021): of 1) familiarisation and data coding; 2) coding; 3) generating initial themes; 4) developing and reviewing themes; 5) refining, defining and naming themes; and 6) writing up. Data analysis included reading and re-reading the transcript and coding using colours and a spreadsheet before themes were identified and verified with the research team.

RESULTS

The five females who participated in the focus group ranged from six to 18 years post-stroke. The ages when they had a stroke ranged from 21 to 63 years (Table 1). Out of the five participants, four were interviewed in person, and the fifth participant selected to join the focus group discussion in real-time through videoconferencing (Zoom).

Four themes emerged from the analysis: impacts of stroke, women’s reproductive health, self-management, and support. These themes and their 11 sub-themes (Table 2) are now described using illustrative quotes.

Theme 1: Impacts of Stroke

The most dominant theme across all the participants was the impact that stroke had on them as individuals. The participants described having a stroke as a moment that suddenly changed their entire, previously busy, independent, and productive lives. These impacts were multiple, affecting every part of the participants’ lives. The impacts were far-reaching and best described using the three sub-themes of stroke onset and early experiences, physical and psychosocial effects, and changes to roles and careers.

Stroke onset and early experiences

The time of stroke onset varied for each of the five women, with the youngest being 21 years and the oldest 63 years. One participant experienced symptoms of a stroke while driving a car (Chloe), and another one while talking on the phone (Linda). Yet, another participant developed symptoms when waking up early in the morning (Liz). Most of the participants experienced headaches in the days before the stroke. Lily described her symptoms: “I’d had five days of a massive headache… when I went down the stairs, I couldn’t see half of the stairs, and I thought something’s not right.” Another participant reported how she felt whole body weakness when she woke up. Liz described the situation by saying, “I kind of woke up, then I went to turn over and hit myself in the face with my arm. I thought this isn’t right, and then I tried to walk to the toilet, and I couldn’t walk.”

Most participants found it very challenging when describing their reaction to being informed they had a stroke. There were some expressions of denial, especially from those who were fit, active, and without risk factors. This is shown in the following quotes: “I didn’t fit [the typical stroke-risk profile] - I was too young, too fit, didn’t smoke, didn’t drink, didn’t do drugs, didn’t do anything” [Chloe]. Liz recalls experiencing a similar reaction:

[A]nd then they came and talked to me, and I burst into tears when they told me I had a stroke… I was in denial that I had my stroke because I think I was so sporty and active, and a stroke happens to someone who doesn’t look after themselves.

Some participants felt frustrated hearing their diagnosis and how they were treated because of being younger. Participants explained their experiences, saying:

And every time I’d go into hospital, it’d be, “Oh, you’ve had a stroke. What do we do?”… but they weren’t quite sure because you’re a young person who’s had a stroke. They don’t really know. [Chloe]

Liz described her experience of receiving a diagnosis of stroke:

So the neurologist came, and all the comments I got were like, “Oh, you’re so young. That’s really weird.” And I was like, “Yeah, that really makes me feel good” [laughing] …. And then they told me I had a stroke… So, they never really gave me a definitive answer which I think for ages really pissed me off cause I wanted to know why so I could fix it, you know… or work towards being healthier or whatever.

This is contrasted by Lala, who described her experience of thinking she might be having a stroke:

I had this massive headache like I’d just been hit over the head with a plank of wood. And I fell over and was vomiting and called the doctor and asked, “Could this be a brain bleed?” “No, it’s a migraine [was the reply].” [I said] “Well, I’m on warfarin, so could this be a brain bleed?” “No, it’s a migraine; get your husband to come and take you home.” Well, because I’m a health professional, I rang my husband and said, "This isn’t a migraine,"and by the time he got me to ED, I was unconscious.

Physical and psychosocial effects

The participants described physical limitations as one of the most serious impacts of stroke that affects them daily. One participant illustrated the most common physical problems related to motor function, movement, and balance. She says, “One side is strong, really strong… my right-hand side is strong, but my left-hand side is probably the age of about a 75-year-old” (Chloe). Participants talked about the impact of their stroke related to speaking, communication, and vision by saying: “I couldn’t speak, I couldn’t read, I couldn’t walk, I couldn’t talk, I couldn’t get off the bed. I couldn’t look” (Lily). More specifically, Linda explained her situation: “I can’t pronounce it because of my speech problems. I couldn’t use a phone and I couldn’t use a mouse for a computer.”

Furthermore, these physical limitations also impacted other life skills, such as using a phone, reading the newspaper or a book, and driving. This then also affected the psychosocial aspects of their lives. Participants, irrespective of their age, shared psychosocial effects after their stroke. For example, the youngest participant Liz said: “I was very much in denial about the fact that I had my stroke, not being able to do everything that my friends were doing.” While the oldest participant shared about her loss of confidence, saying, “I think that [the stroke] took so much of my confidence. And that was a real challenge for me as a woman because there were things I could do automatically before” (Lily).

Changes to roles and careers

The women described experiencing serious impacts of stroke on their roles and careers, though some initially tried to continue as before. Lala describes her changing situation, “I tried to return to work. I was a midwife and tried hard, but it didn’t work. And then, I was trying hard to return to my quality role, which didn’t work either. So now I don’t work.” Lily illustrates her experience:

I tried to run my household, and that didn’t work because I’d run out of battery power [referring to her lack of energy]. But I still had to run the family… and at my age, I was 50 something, and to lose my confidence after being a fully-fledged businesswoman for my entire life, 220 staff, never being unable to make a decision. I have never been unable to do what I wanted.

The youngest participant Liz, expressed how the stroke delayed her first job opportunity:

And this all happened a couple of weeks before I was meant to start my first job as an OT [occupational therapist]. So I had to put my work on hold 'cause I wasn’t well, I had to have four weeks off.

Theme 2: Women’s Reproductive Health

Under the theme of women’s reproductive health, there were three common issues: pregnancy, the use of the contraceptive pill, and complications of anticoagulants on menstruation.

Pregnancy

Getting pregnant became a big concern for some of these younger women after their stroke. One participant, Lily, shared how she worried earlier about whether to have children because she was on medication. She said: “I’ve got anticardiolipin in my blood, so there was a high risk of me aborting or losing children.” Another participant expressed her desire to have children by saying: “I haven’t got children yet. I need to talk to my gynaecologist. That’s something I’m looking at doing” (Liz).

On the contraceptive pill

Being a woman and menstruating is a normal event, and while the contraceptive pill is commonly used for birth control, in some situations, such as prolonged or heavy periods, the use of the contraceptive pill may contribute to stroke risk. Liz explained how using the pill was her only risk factor and that she knew someone else who had a stroke also had this same risk factor saying:

I was on the pill for heavy periods, just like the norm. So, that was my only risk factor… And we’ve got someone else in our stroke group. She was on the pill and had a stroke, too.

Effects of anticoagulants on menstruation

Another serious problem expressed and described by one participant was her heavy menstrual bleeding due to the anticoagulant medication she was taking for stroke prevention:

They put me on warfarin and aspirin, and immediately, I had ridiculous bleeding. Like, my periods would last for three weeks, then I’d have a week’s break, and then it would start again. And it’d just be so heavy that then I was anaemic, and then I had the Mirena [intrauterine device for heavy periods]. [Lala]

Theme 3: Self-management

Overall, the participants were keen to manage their health and remain healthy after their stroke and three sub-themes illustrate this.

Being a woman

The participants described their motivation to recover and based a lot of their determination on being a woman and regaining the ability to do all the things they needed to do as a woman. “Cause it’s a real issue for women who run a family, and as women, we run the family nine times out of 10” (Lily); “And every single day, every single day, I do still rehabilitate myself. I think we all do that” (Chloe).

Healthcare monitoring

Many of the women described elements of self-care management following their stroke. They described some healthcare monitoring activities they regularly performed to manage their physical and mental health and well-being. Two participants explained how they monitor their blood regularly because they are on anticoagulants. One participant self-checked at home: “I monitor myself at home, so I don’t go through the monitoring regime of going to the lab. I have a ‘CoaguCheck’ at home, and I do it because I’m brittle” (Chloe). Another participant’s routine included weekly blood tests through a laboratory: “I do mine once a week, but I go to the lab” (Lala). Participants indicated they were still taking stroke prevention medication after several years. Chloe reported, “I had Clexane, I did Clexane every single day, and I found that easy,” while Liz used another medication, saying, “I’m on Clopidogrel.”

Self-care

Even though it has been a few years since their stroke, most participants understood that they still had physical, emotional, and health needs. In addition to medication, three individuals shared their experiences with physical activity and mindfulness programs, such as yoga and tai chi for fatigue management. Participants discussed their fitness routines and their experiences with various programs. Linda reported, “I do all the exercises every second day now.” Lily expressed the benefits of her exercise program saying that, “the breathing and the mindfulness aspect of yoga are really important for fatigue.” Chloe and Linda also continue to participate in physical therapy daily. “Every day, I still rehabilitate myself with walking, doing academic stuff every day, to make sure that I’m doing brain work, and walking work, and doing” (Chloe). Chloe, who had her stroke 18 years ago, underlined the need for long-term support, such as a wellness emphasis rather than an illness focus, for stroke survivors:

We need to stop talking about a disease focus and start talking about a wellness focus. Everything’s pitched for the early days, and nothing is pitched for the lifetime of a stroke.

Theme 4: Support

The women stroke survivors in this study described needing long-term support and funding for life after their stroke. They realised internal (from their own motivation, partner or family) and external support (from outside themselves and their immediate family) had helped them cope post-stroke.

Internal support

Participants described how the internal support from partners, family, or even their own motivation, was powerful and helpful. One participant expressed how her partner fulfilled daily needs by saying, “My partner was really good; he was showering me and cooking and feeding me, putting me to bed” (Linda). Another participant felt she would have collapsed without the support from her husband, “If it hadn’t been for my husband being able to drive me, I’d have been stonkered” (Lily). This participant further described how she had to carry on and motivate herself to do everything she could:

Every single day we’re challenged with everything… we don’t have a choice. We’ve got to carry on and do everything we can… You have to challenge yourself, do stuff you’ve never done before.

External support

External support was described as support from outside the woman and her close family and friends. The women described essential, external support as the stroke group many of them attended. Here women made connections and supported each other. Participants explained how the stroke support group was beneficial and supportive during their life after stroke: "Everybody takes a plate [food to share], and we sit around and talk, and it’s a group that has been so supportive (Lily). Lala also described the stroke group she attended: “We have a stroke support group …. and that gives me a real sense of purpose.”

One participant described benefiting from funding support received from the Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC) early in her post-stroke journey, due to complications of treatment she had received. ACC is part of Aotearoa New Zealand’s health system that supports recovery after accidents or medical misadventures. She described her experience in the early days of stroke: “I’ve had heaps of support. I’ve had psychologists, occupational therapists… been under ACC”, but she also implied that it’s “…kind of like hard now, to get any support” (Lala).

Unlike stroke survivors who live in the city, some participants who live outside of town or in a rural area expressed that they had limited access to rehabilitation services which made them feel very isolated:

I never had any help either, nothing… absolutely nothing. But eventually, we got hold of the [organisation] and we asked if we could have some help, even if it were housework, cooking a meal, or just something. And they said, “No, you live too far out of town.” I got no rehabilitation at all. [Linda]

Participants agreed that based on their limitations and difficulties, having access to software that helped them manage their recovery would have been beneficial: “It would be good to have an app, and then you could kind of have chapters, but like little icons that you could then click onto, or tap things” (Lala). Liz adds, “You can get apps that… you know, that if you open it, then it can speak to you,” and Lily agrees, “You can speak to them [the app], and it recognises your voice.”

DISCUSSION

This study describes five women’s experiences following a stroke from six to 18 years ago. The women were aged between 21 and 63 years old when they had a stroke, which is younger than the 76 years most women experience a stroke (Akyea et al., 2021). This aligns with an increasing trend of almost fifty percent of new stroke cases occurring among younger people (G. Jackson & Chari, 2019; Zhang et al., 2022). Despite the small number of participants in this study, their experiences varied and show that even if someone had a stroke some time ago, they still need ongoing support and attention. Some themes and experiences from this study were quite similar to a study of Norwegian women post-stroke, notably concerning four distinct phases: physical changes, managing activities, self-understanding and going on with life (Eilertsen et al., 2010). This Norwegian study can guide healthcare professionals in many countries, including Aotearoa New Zealand in identifying which concerns require more attention at each phase of recovery and for providing the support necessary for patients to continue their recovery.

Stroke causes a serious impact on women because women not only have the burden of typical symptoms but also experience atypical symptoms such as headaches, mental status changes, and dizziness more frequently than men (Ali et al., 2022; Newman-Toker et al., 2014). Headache was one of the atypical symptoms experienced by almost all participants in this study a few days before their stroke. Several studies have reported that female stroke patients often report atypical, non-focal, and non-traditional symptoms (Branyan & Sohrabji, 2020; Girijala et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2022). Atypical stroke symptoms are defined as symptoms not included in ‘Balance, Eyes, Face, Arm, Speech, and Time’ (BEFAST), which according to the American Stroke Association are the stroke warning signs and symptoms (Eddelien et al., 2022). Due to having atypical initial symptoms, the participants in this study experienced frustration when facing uncertainty from health workers, delayed and mis-diagnosis. This finding is similar to a review that noted the frequent misdiagnosis of young female stroke patients; leading to missed opportunities for early treatment, rehabilitation, and prevention of recurrent stroke (Newman-Toker et al., 2014).

In addition to the physical impacts, participants in this study described psychosocial impacts, such as denial because of the inability to do everything others can, loss of confidence, reduced functional independence, and hopelessness. Furthermore, the meta-analysis by Mou et al. (2021) emphasised that reduced functional independence was one symptom of depression, and the rate of depression in young women after a stroke is almost double that of depression among men (Caponnetto et al., 2021; Eddelien et al., 2022; Leppert et al., 2020). The physical and psychological impacts experienced by women after a stroke at a young age are also recognised as seriously impacting their role and career as a woman (Lo et al., 2021).

This study highlights and explores some unique issues women face following a stroke, including the use of contraceptives, anticoagulants, and potential pregnancy problems. These findings are supported by literature that reported regular oral contraceptive use, even in a low dosage, increases the risk of ischemic stroke (Ornello et al., 2020; Saddik et al., 2022). In their current guidelines, the European Stroke Organisation also suggests that pregnancy is one of three vulnerable periods for women to experience an ischemic event (Kremer et al., 2022). The use of anticoagulants is somewhat effective for stroke primary prevention; however, it is also associated with an increased risk of bleeding (Gdovinova et al., 2022).

The women in this study described their motivation to recover because they are women and needed to run their family home and return to work; they had a sense of urgency to recover and return to their lives. This motivation can be seen as a positive aspect of post-stroke self-management in terms of maintaining health and preventing complications. This finding is similar to studies among African Caribbean women, where self-motivation became a strong coping mechanism for living life after a stroke (Moorley et al., 2015).

Synhaeve et al. (2016) suggest that young stroke survivors’ prognosis is poor, with one in eight survivors unable to live independently. The women in this study all wanted to get on with their lives but wanted support to achieve this, which aligns with the findings from (Andrew et al., 2014) about the importance of tailored support, self-management, and practical help for those living after a stroke to ensure it meets the younger stroke survivors’ unique and specific needs. More specifically, the participants in this study described how they needed ongoing support for their longer-term well-being, even up to decades post-stroke. This finding aligns with recommendations of two systematic reviews on the need for collaboration from multidisciplinary stroke teams, which should include stroke survivors, caregivers, healthcare providers, health services, and community stroke support structures, as this is the way to best meet the stroke survivors’ needs (Boehme et al., 2021; Hartford et al., 2019). Participants from this study reported that peer support through stroke support groups was a significant benefit. This is in line with literature that suggests peer support improves physical and psychological outcomes (Wan et al., 2021).

The Stroke Action Plan for Europe 2018-2030 has also raised the issue of the importance of better long-term management of stroke patients considering various problems which may be faced, such as unmet post-stroke needs, the burden of post-stroke complications, residual deficits, and the risk of recurrent vascular events (Norrving et al., 2018). Based on participants in this study, access to health care for those stroke patients living in rural areas is still an issue. This finding also confirms a 2022 study that found stroke survivors in rural and remote areas want to live well, doing what matters to them, despite their challenges and possible isolation (S. M. Jackson et al., 2021). Young stroke survivors endorsed online service delivery as a preferred method to solve the unmet needs of living with stroke (Keating et al., 2021). It has also been suggested that a combination of self-management and telehealth could offer promising interventions (Saragih et al., 2021). Telehealth applications can be particularly helpful for messaging, telephone, video conferencing, and online platforms and these are very applicable for patients at home otherwise limited by time and distance (Anderson et al., 2022; Hwang et al., 2021).

Studies have shown that stroke incidence is higher in women, who often experience poorer outcomes than men (Bushnell & Kapral, 2022; Xu et al., 2022; Yoon & Bushnell, 2023). Therefore, post-stroke support systems must be specifically tailored to women’s unique needs. These support systems should be designed to address issues such as activities of daily living, anxiety, and health-related quality of life in both physical and mental domains (Xu et al., 2022). By providing targeted care and support to women post stroke, their recovery and overall quality of life can be maintained and improved.

Implications for improving care and rehabilitation for younger women after stroke

This study has highlighted that recognising stroke among younger women can be difficult because of atypical symptoms. The failure to recognise atypical symptoms can lead to a double burden related to delayed treatment, rehabilitation, and implementation of prevention measures to reduce recurrent stroke; plus, women are more likely to experience depression after stroke. Insufficient research focusing specifically on women has led to a lack of sensitivity and specificity in assessing stroke symptoms in women, resulting in stroke assessment tools designed only to recognise common symptoms (Colsch & Lindseth, 2018). A recent article entitled “Stroke in women: still the scent of a woman” emphasises the complexity and variability of female physiology over a woman’s lifespan, including pregnancy, lactation, menopause, and the long period after menopause, which is very different compared to men (Kim, 2023).

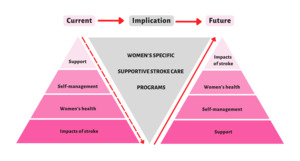

The experiences of younger women stroke survivors provide valuable insights. The themes from this study can be presented as a pyramid-like structure (see Figure 1). The first layer describes women who reported the biggest impact of stroke on their lives. Secondly, unique, and specific risk factors affect women throughout their lifespans. Thirdly, women need to control their health within their abilities and to meet their roles. Finally, the small upper layer reflects the limited support available to women stroke survivors, despite the magnitude of the impacts they experience. It is crucial to reverse this pyramid by providing optimal support to women stroke survivors, such as women’s specific supportive stroke care programs to minimise the impact of stroke as this has the potential to improve women’s post stroke quality of life and outcomes.

The challenges younger women face after a stroke are complex and enduring. The long-term consequences of stroke and its many residual complications can have a negative impact on the physical and psychological well-being of the individual and their caregivers, which can then affect the stroke survivor’s recovery (Qureshi et al., 2022). Therefore, specific strategies for post stroke rehabilitation for younger women is needed to optimise their health and well-being.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include the small number of participants. Even though the participants had all experienced a stroke at a younger age, there were differences in the length of time after their stroke. These differences may have affected their perception and experiences. A further limitation is that while this study identifies the experiences and needs of the participants, this is without considering confounding factors such as the characteristics of the participants, like their working status and the presence of a partner/carer/caregiver. Finally, the low heterogeneity of participants (with none being Māori, the Indigenous people of ) Aotearoa New Zealand means this study cannot be generalised across those of different cultural backgrounds.

Future Research

Globally, stroke cases have increased significantly, with stroke affecting more younger people, especially women. This phenomenon might be due to low awareness of stroke risk factors that are unique to women. Basic studies on awareness of stroke risk factors in younger women are needed to determine effective education. This study reinforces that younger women who have had a stroke will face complex and different burdens from older adult stroke patients. Further studies on specific management and interventions focusing on the needs and experiences of younger women are needed to improve their quality of life and well-being.

CONCLUSION

The stroke burden experienced by younger women is more complex but less explored than for older populations. This study identified four main themes: the complex impacts of stroke on women at a younger age, the specific correlation with women’s reproductive health, challenges in post-stroke self-management, and the importance of internal and external support. There is a need to develop specific strategies for women, starting from prevention, treatment, and ongoing support for more effective stroke rehabilitation in the future.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to all participants who contributed to this research

Funding

None

Conflict of interest

None