INTRODUCTION

Addison’s disease, also known as primary adrenal insufficiency, is a rare endocrine condition where the adrenal glands are unable to produce enough of the hormones - cortisol and aldosterone - key to sustaining vital bodily functions (Bensing et al., 2016). There is no epidemiology data for Addison’s disease in Aotearoa New Zealand, although internationally the prevalence in western countries is estimated to be 118 per million population (Chabre et al., 2017). With daily doses of physiological steroids, patients with Addison’s disease can keep themselves well, however, when the hormonal balance of cortisol is disrupted due to stress (physical or psychological) patients with Addison’s disease are at risk of developing a life-threatening adrenal crisis (Bornstein et al., 2016). The possibility of hospitalisation also increases, and it is important to understand the patient experience to reduce patient anxiety and avoid the potential risk of mortality associated with an adrenal crisis.

Review of related literature

Research on Addison’s disease and adrenal crises has taken various methodological routes but often stops short of exploring the nuanced lived experiences of patients. Studies like those by Hahner et al. (2015) and Mälstam et al. (2018) for example, examined the medical and educational aspects of Addison’s disease. While Hahner et al. (2015) emphasised patient education as a preventive measure for adrenal crises, Mälstam et al. (2018) revealed that patients often find themselves navigating the complexities of their disease largely on their own. Other studies have focused on quality of life (QOL) as a measure for patient experience (Ho & Druce, 2018; Li, 2022). Although these studies report some useful findings, they all demonstrated a lack of clarity in defining what exactly constitutes QOL and the essence of living with adrenal crisis.

Importantly, practical management challenges during stressful medical situations were highlighted by Jung and Inder (2008), but they did not provide a universally accepted glucocorticoid supplementation regimen. Others have provided a framework to capture patient journeys, though these are either not specifically for people living with Addison’s disease (Webb et al., 2022), or have a different disease context, such as the lived experiences of people with adrenocortical carcinoma (Yeoh et al., 2022). Despite these diverse approaches, no research could be found that delved into the lived experiences of people living with Addison’s disease undergoing hospitalisation for an adrenal crisis, and notably, no one has considered the healthcare context of Aotearoa New Zealand. This points to a critical gap in the literature that the present study aimed to address.

Using a phenomenological lens, which is a qualitative approach that aims to understand the emotional, psychological, and physiological components of a patient’s experiences, will contribute to both clinical practice and healthcare policy. This study aimed to examine the lived experiences and essences central to patients with Addison’s disease when they are hospitalised due to an adrenal crisis. We answer the question: “What is the lived experience for individuals with Addison’s disease who have been hospitalised due to an adrenal crisis and how can this inform healthcare staff?”

METHODOLOGY AND METHOD

This qualitative research was informed by the principles that underpin Heidegger’s interpretive phenomenology (Carpenter, 2013). Phenomenological research aims to reveal the individuals’ lived experiences and the essence of the health event they encounter. Heidegger’s framework enabled us to explore the phenomena central to the experience of living with Addison’s disease, such as the emotional, psychosocial, and physiological aspects of an adrenal crisis. Research of this nature does not assume understanding, rather works to develop knowledge by using meanings constructed by the participant (Carpenter, 2013). This is key to the interpretation of the rich information gleaned and due to the rare and intricate nature of Addison’s disease nuances could be missed if a descriptive rather interpretive phenomenological approach was used.

Positionality statement of first author

As the first author (SF), my interest in this research came from my work as an endocrinology clinical nurse specialist. Through my work observing and talking with patients I noticed that patients being diagnosed with Addison’s disease have different journeys from diagnosis to managing day to day life. I was concerned that nursing and medical staff often struggled to identify and support patients with Addison’s disease particularly when presenting acutely during an adrenal crisis which had a significant effect on the patient and whānau experience. Through this research, I hoped to gain greater knowledge and understanding of what it is like to experience an adrenal crisis to provide improved care and patient outcomes. This research was undertaken in partial fulfilment of a master’s dissertation.

Ethical considerations

Research approval was granted from WINTEC Human Ethics in Research Group (HERG) (Approval No. WTFE06270521) and the local health authority. Participation was voluntary. Eligible participants were fully informed of the research and signed consent forms prior to being involved in the research. To uphold ethical principles and protect anonymity, pseudonyms were utilised. Self-chosen pseudonyms can enhance the investment and connection to the research by participants (Vandermause & Fleming, 2011).

Sample

Six participants were recruited via the New Zealand Rare Endocrine Disorders (RED) registry. Their lived experiences provided intentionality and richness to the study, capturing the essence of what it means to be a patient with Addison’s disease in Aotearoa New Zealand. Participants identified by the register were sent the research information including contact details for the researcher to whom they could contact and show their interest.

Participants were distributed evenly by gender, and all were New Zealand European, ranging in age between early 20s to 85 years. The number of adrenal crises events experienced was self-reported by the participants and ranged from one to more than five. Participants experienced over 23 adrenal crisis events in total, with 15 resulting in hospitalisation. This distribution is in keeping with international literature, particularly that the duration of diagnosis does not correlate with the number of crises (White & Arlt, 2010). Additionally, the ethnicity data is consistent with the international literature which demonstrates higher prevalence for Europeans having Addison’s disease compared with Indigenous populations. However, there is a lack of data in Aotearoa New Zealand to fully understand the prevalence for Māori. Table 1 summarises participant demographics.

Data collection

Participant experiences were captured through semi-structured interviews conducted via Zoom or where possible in person. The aim of the semi-structured interviews was to capture rich and in-depth explorations of the patient experience when living with Addison’s disease, experiencing an adrenal crisis and hospitalisation. Interviews were audio recorded. Four interviews were conducted via Zoom (n=4) and two were face to face (n=2). The interviews lasted between 45 and 60 minutes.

An interview schedule was used to guide the interviews and included open ended questions such as:

-

Can you tell me about a time when you experienced an adrenal crisis?

-

What do you remember from steroid education?

-

What do you remember from your hospital experience?

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim, and a thematic analysis drawn from the collected information (Braun & Clarke, 2012). The thematic analysis was conducted by the first author (SF) with all aspects of the transcripts grouped under a range of themes. A review of the analysis and feedback was then provided by the co-authors. Using Heidegger’s interpretive phenomenological lens, we identified key experiences that formed the essence of living with Addison’s disease and being hospitalised during an adrenal crisis.

Rigour strategies

We established trustworthiness through several means. Credibility was assured through the thick description of participants’ lived experiences, facilitated by the interpretive phenomenological approach (Cypress, 2017). This allowed for an in-depth exploration of patient experiences, enabling participants to freely share their stories. Transferability was demonstrated by providing rich context and detailed accounts that allow readers to assess the applicability of the findings to other settings or populations (Cypress, 2017). Dependability and confirmability were achieved through an audit trail, consisting of the research process and raw data, which can be examined by external reviewers to verify the research outcomes (Cypress, 2017).

FINDINGS

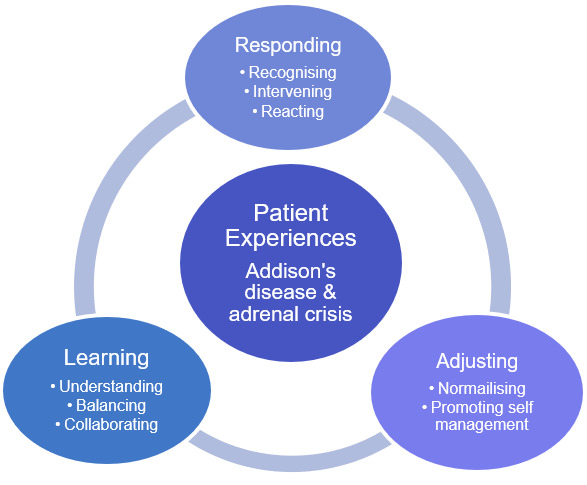

Through the experiences of Charlie, Ricki, Dolly, Katie, Noel, and Mary (pseudonyms), the themes and concepts of responding, adjusting, and learning, and how these interact to explain the patients’ experiences of Addison’s disease adrenal crisis were conceptualised. Responding is derived from the participants’ views of their diagnosis and their responses to experiencing an adrenal crisis. The participants shared experiences of their condition which illuminated how they adjusted to having Addison’s disease. This was seen as a period of normalising and developing self-management of their condition. A key aspect of living with Addison’s disease is a learning phase. Participants shared how they gained knowledge to manage their day-to-day life of taking the required daily physiological doses of steroids. This knowledge supported their ability to maintain physical health with regular steroids and ward off an impending crisis by increasing steroids at the appropriate time.

Table 2 provides a summary of the themes and subthemes that explain the patient experience of Addison’s disease, adrenal crisis and hospitalisation. This is used as a framework for reporting the findings from this enquiry.

Theme 1: Responding

Responding included the subthemes of recognising, intervening and reacting. These encapsulated participant experiences around a diagnosis of Addison’s disease, adrenal crises events, the intervention that takes place, and how participants react in times of crisis. Recognising Addison’s disease has numerous nonspecific symptoms such as lethargy, muscle weakness, weight loss and nausea alongside some specifics such as hyperpigmentation and salt cravings (Allolio, 2015). This is captured by the participants explaining the symptomatology they encountered.

Being tired…, being weak… I think he [doctor] noticed the colour of my skin…he looked at the palms of my hands which was kind of weird…this [Addison’s] is such a gradual thing that I just had no energy for life. [Charlie]

With regard to recognising an adrenal crisis some participants were unsure. Katie stated:

I don’t know if it was actually adrenal crisis or if it was just me being sick and then my Addison’s made it worse.

Having recognised that something was amiss, intervening is a key part of managing Addison’s disease and adrenal crises. Participants described their experiences of ambulance care, hospitalisation and input from the endocrinology service. Ambulance service intervention varied with one participant describing an easy path to the hospital via ambulance:

Being able to communicate well with the ambulance driver and they always call ahead of the hospital [was effective for early intervention]. By the time I get to the hospital. They know exactly what’s going on. [Ricki]

Another though described having a significantly daunting journey without having their intramuscular (IM) hydrocortisone administered:

I did end up in hospital and that was when the paramedic who had to call their boss was like, do I give it [hydrocortisone], do I not? And they’re like well it’s not going to be bad for her. But like probably you could or like, you can wait to give it here [hospital]. It was a 40-minute trip… rushing till we got there [hospital]. [Katie]

Hospitalisation was described by participants as both positive and negative experiences. Positive experiences included swift treatment on arrival to hospital:

It’s always been really good at hospital. Always incredibly switched on and I’ve never sort of come across a problem. They’re always quick to give me the injection [hydrocortisone] and getting me on track with fluids. There never seems to be any confusion about the processes, which is good, considering it’s [Addison’s] a relatively rare thing. [Ricki]

Other participants, however, experienced negative experiences centred on having to wait for treatment:

Because no one really knows about Addison’s. I still get people [health professionals] saying like “What’s that?”… and I have to go through and try [to explain]…. One of the first times in adrenal crisis they [emergency department staff] were really like nit-picking at what things were and trying to say that you don’t need this… The hardest thing I think was some of the doctors not knowing, and the nurses not understanding what Addison’s was. My partner would get frustrated because you know you wait for hours and hours and hours and hours and then when I got in there, they’d be like oh shoot you actually really need help, but we’ve had you sitting in the waiting room for four hours…Probably the most frustrating thing is getting across to them how important it is and how urgently I needed help. [Mary]

Endocrine support was the biggest concern for participants wanting to know that specialist oversight was provided by endocrinology and that their specialist had been involved in their care.

They were just kind of dealing with it at an ED [emergency department] level…having someone from that team [endocrinology] that understands it more, to actually come down [to ED]…I don’t know if there was any communication between those kind of departments and I feel like that would be beneficial. [Katie]

Reacting in a timely way is an essential component of responding to an adrenal crisis. During an adrenal crisis a steroid injection is the required treatment as it has a rapid response that prevents the life-threatening occurrence of adrenal crisis. Due to the rapid decline towards an adrenal crisis participants are provided with their own injectable steroid. When asked if they had ever given themselves an injection, participants revealed they were either too ill, preferred not to administer the medication, or didn’t think they needed the injection at the time:

I guess being a typical pig-headed kiwi bloke, probably always avoided getting jabbed with the needle even though I always had the intravenous cortisol [at hospital]. [Ricki]

Mary discussed how over time how her reactions to a crisis evolved. The recognition of a crisis occurred quicker over time, leading to quicker reactions and intervention.

The more crises I had, and the more admissions I had, I knew that once I had been on the drip and had all that stuff [steroids and intravenous fluids] I felt better. I was quicker to go to the hospital…I just wanted to get the cortisol and feel better… In the beginning I’d sort of leave it a few days and then go to get help. [Mary]

Theme 2: Adjusting

The theme adjusting reflects participant recognition of the adjustment that occurs when dealing with an Addison’s diagnosis and the experience of an adrenal crisis. For the participants this was illustrated by themes of normalising life with Addison’s disease and promoting self-management. Normalising in this context was expressed by participants as the ability to adjust from being unwell, to getting a diagnosis and getting back to their normal life. Participants shared examples of resilience in interviews. This was highlighted by their own expression of how they felt about their diagnosis and their own ability to carry on with life.

I didn’t find that a particularly strange issue or anything. I have no problem, with doing that, taking the steroids. [Ricki]

Noel reflected his acceptance of his situation:

I’ve just accepted that I have Addison’s and there’s somethings I can do some things I can’t do just go on with life.

From the experiences shared by the participants, there was an attitude that displayed resilience in dealing with their diagnosis. This did not appear to change with different ages at diagnosis. One notable aspect, however, was gender. Male participants’ attitude to their diagnosis appeared to normalise earlier than the female participants. In this research this was evidenced by the difficulties females shared with their diagnosis compared with the ease of the male participants. Mary described her initial thoughts regarding her diagnosis:

When I was first diagnosed I was really mad. I was like, why the heck is this happened to me and I kind of just didn’t really listen much and I didn’t get it.

Mary’s attitude changed as time passed and reflected her normalisation of Addison’s disease:

To be honest I’ve gotten it now…I don’t have to think about it, I take my pills in the morning at lunchtime and that’s about it really I don’t really think about [it]. Sometimes I forget, until I see my bracelet and I’m like oh yeah.

Katie expressed her unawareness of the significance of her treatment to keep her Addison’s disease under control:

Had I known to keep it [Addison’s disease] steady I’m sure I’d probably be at a beautiful point with my meds now, but I guess that it’s just life.

Promoting self-management occurs in a number of ways one of which is preparedness. As an illness can occur at any time, participants highlighted the need to be ready to increase their steroids to ward off a potential adrenal crisis. For them this meant having adequate supply of steroid medication and maintaining a partnership with their primary healthcare provider. A recommendation for patients with Addison’s disease is to have access to their life saving medications on hand at all times. This means keeping a large supply of hydrocortisone that is easily accessible for regular dosing and sick day management (Addison’s Self-Help Group, 2021). For the participants, this required ensuring other members of their healthcare team such a general practitioners, nurse practitioners, and nurses were aware of the importance of having hydrocortisone available. The adjustment part of the journey with Addison’s disease seemed to be when the patient was able to advocate for themselves and be self-prepared for a potential adrenal crisis.

They [endocrinologist] loaded me up with so much cortisone right at the beginning that the pharmacist was actually questioning how much I was getting and making sure I was being monitored. But in his [endocrinologist’s] mind it was very much to put stashes everywhere, like you know just to make sure that you don’t run out. [Charlie]

Theme 3: Learning

For participants learning about Addison’s disease and crisis can occur simultaneously with the responding and adjusting phase. Learning is influenced by underlying subthemes of understanding, balancing and collaborating. The experiences shared by the participants illustrate how these impact learning that occurs with a diagnosis of Addison’s disease.

A key aspect of learning is understanding where a significant amount of knowledge needs to be processed and understood. This includes understanding of Addison’s disease and steroid management necessary for participants to be able to independently self-manage their diagnosis in day-to-day life.

Sometimes knowledge is good…[but] nobody has sat down and told me why I’ve got Addison’s. [Noel]

Katie identified her level of fear and need for education:

I feel like the education around the actual symptoms could be something that I personally need… probably it would have been crucial for me to educate myself around it. I was too intimidated and too scared to ask because I was so scared of that doctor.

Steroid education differs from education surrounding Addison’s disease where its specific function is to inform patients about their medication and how to use this to manage their health and well-being following a diagnosis of Addison’s disease. Medication education is usually a primary focus of the education provided as it is viewed as key information that patients require to be self-sufficient and avoid adrenal crisis.

When participants were asked about their steroid education sessions and memory of the steroid education the responses, Katie recalled “Absolutely nothing” and thought a refresher would be good. Mary couldn’t recall much of the education and felt she’d “learned more and more as time had gone on.” Ricki, on the other hand identified how the initial learning was “definitely a little bit of a crash course” and if you just take the pills, “everything should kind of be okay.”

Balancing refers to the delicate nature of the Addison’s disease diagnosis and maintaining a normal day-to-day life. Balancing involves the art of maintaining wellbeing by taking daily steroids and increasing these in times of illness to prevent a life-threatening adrenal crisis. Participants revealed that they believed that finding balance by navigating the unpredictability of Addison’s disease is facilitated by engaging family support, who were key to feeling safe and supported as they had the ability to advocate for them during crisis:

They [my family] hated it…they didn’t know what to do…especially mum and dad, they were like, well, we don’t even live close to you…She [mum] knew straight away when I was ringing her that something had gone wrong. [Mary]

Mary discussed how initially her partner had to really push her to get the help she needed due to her feeling like she didn’t need any help to work through the period of being unwell. Over time this changed and Mary learnt that the situation could be remedied quicker with earlier intervention that her partner was advocating for:

So, it kind of got to a point where he [partner] put his foot down a bit and be like right we’re gonna go and get seen and see what’s going on…. He was really good at [advocating], because I was a bit stubborn and just didn’t want to go and get poked and prodded and…yeah so he saw it from a different angle than what I was seeing it.

Collaborating acknowledges the value in having the ability to meet with other people diagnosed with Addison’s disease. Social media was identified to be highly beneficial to enable connections with people from your own community for support:

It’s such a rare thing … I just felt like a kind of like alien because I was like I’m the only one [Addison’s patient]. There’s not many in New Zealand that have it. [Mary]

Mary was able to connect by joining the the Facebook Addison’s page.

DISCUSSION

The close relationship of themes and the way these influence the lived experience of participants with Addison’s disease is demonstrated in Figure 1. This conceptual model holistically explains the various elements of medical and non-medical experiences of patients with Addison’s disease as discovered through this enquiry. Addison’s disease and adrenal crisis patient experiences demonstrated responding, adjusting and learning as being at the core for a person living with Addison’s disease. This model is used as a framework to discuss the findings of this study.

Although individually, themes represent key events in the participants’ experiences, the concepts underpinning the themes represent a broader picture. These are not experienced in a linear fashion nor independently of each other. The three themes of responding, adjusting, and learning surround Addison’s disease in a wrap-around pattern and has been illustrated in this way (without arrows) to demonstrate the fluidity of the participant’s experiences. It is important to acknowledge that this will occur continuously as they encounter life changes, or adrenal events. The participants responded to changes in their health status, or life events in which they adjusted and learnt to prevent further issues in the hopes of living well with Addison’s disease and avoiding adrenal crises.

From this study all findings centred on the diagnosis of Addison’s disease. The experiences of being diagnosed as shared by participants was consistent with other literature. The journey to diagnosis is experienced as long and vague with patients encountering multiple healthcare professionals and undertaking multiple interventions (Allolio, 2015; Hahner et al., 2021). The symptoms of Addison’s disease include fatigue, poor well-being, postural dizziness, nausea, and weight loss, and these symptoms are frequently attributed to other illnesses with similar symptoms (Allolio, 2015). Hyperpigmentation is a more specific indicator of Addison’s disease, though usually occurs later on in the disease pathway (Allolio, 2015). Adrenal crisis is a further key indicator, as experienced by our participants, in confirming an Addison’s disease diagnosis. The delay in diagnosis impacts wellbeing and quality of life and places the patient at risk through adrenal crisis (Ho & Druce, 2018; Li, 2022). Increasing awareness and knowledge of healthcare practitioners in primary and secondary settings will improve the rate of diagnosis and reduce the risk of a life-threatening adrenal crisis.

Responding, adjusting, and learning were central themes identified through participants’ experiences, which have a significant impact on the life of a person with Addison’s disease. These themes and subthemes resonate with the findings of Mälstam et al. (2018) who explored the everyday living and managing of Addison’s disease. They found, for example that patients needed to fine tune or make adjustments in their everyday life; develop knowledge and support systems; become an expert in their own health; and balance and find new ways of living (Mälstam et al., 2018). In our study, the data from the participants are small snippets showing the relevance of the conceptual model (Figure 1). Mary’s descriptions of her journey illustrated the model. Mary shared how over time her recognition of Addison’s disease and adrenal crises changed as her journey over time progressed. Importantly, Mary began to recognise and intervene quicker as her understanding of the impact of each crisis became clearer, aided by significant family support and their advocating for timely treatment. Her ability to recognise and intervene in response to worsening health as a result of an adrenal crisis were part of her adjustment and learning to manage her chronic illness.

Chronic illness is complex with multidimensional aspects to manage for patients with Addison’s disease. Medication management and the use of blister packs is particularly valuable for people requiring multiple medications. For people with complex chronic co-morbidities, Zedler et al. (2011) identified how the use of blister packaging in combination with education improved adherence, prevents complications and hospitalisations, while avoiding a decrease in quality of life. For example, Mary gained control over her symptoms of Addison’s disease and removed the feelings of being overwhelmed from her everyday life through the use of blister packs. As a result, Mary had been able to focus and gain a deeper understanding of Addison’s disease, significantly reducing her potential for adrenal crises.

Listening and understanding the journey described by participants reduced feelings of being overwhelmed. Over time, and through experience, participants identified how they responded to crises, learnt and adjusted their responses, and as a result improved their management and timely access of healthcare in an adrenal crisis. Rogers (2009) discusses self-management being a central principle in health care for chronic illness and the patient is viewed as the expert by virtue of the experience of living with a chronic disease such as Addison’s disease (Mälstam et al., 2018). Over time, participants were able to limit the adrenal crises experienced and the negative impact these had on their life as they became more fluent in managing their condition. Given the low prevalence of Addison’s disease and the variability in patient experiences, it is possible to individualise daily steroid management of Addison’s disease and education plans to prevent adrenal crises. Shepherd et al (2022) discussed the use of behaviour change theory to aid in self-management rather than relying on a purely educational model. This was identified in previous work where some individuals with Addison’s disease continued to have adrenal crises despite being well educated (Shepherd et al., 2017).

This study confirms much of what is anecdotally known about Addison’s disease amongst endocrinologists and endocrine nurse specialists worldwide. Having an understanding of the patient perspective is invaluable in offering insights for healthcare professionals to support their patients. In particular it is valuable for the nursing workforce to understand the implications of living with Addison’s disease as they work closely with patients in roles of primary carer, educator, and advocate. Nurses and nurse practitioners are well placed to improve their patient’s understanding of how Addison’s disease and adrenal insufficiency impact health and optimal ways for managing the condition to promote quality of life and wellbeing.

Limitations

This was a small study as part of a Master’s thesis. It was further limited by the reliance of recruitment using the Rare Endocrine Disorders Registry (2023), which is a new entity in Aotearoa New Zealand and still in an early phase to register patients. Some participants were known to the researcher. While this may encourage open discourse, this may have prevented participants from being completely open about their experiences. All participants were of European descent, resulting in a view that is from one cultural perspective. Including the experiences of people with other cultural perspectives would provide further insights important to individualised care for people living with Addison’s disease. Despite the limitations this study highlights the value of participants insights and how this information will provide meaningful benefits to both current and future patients diagnosed with Addison’s disease as well as health professionals working with people living with Addison’s disease.

Recommendations

Findings from this study have significance for people diagnosed with Addison’s disease. The participants’ experiences have contributed to the development of the Addison’s disease and Adrenal Crisis Patient Experience Model which requires further development and testing in practice. Of note it is recommended:

-

Development of a structured education programme for patients newly diagnosed with Addison’s disease utilising strategies to build resilience.

-

Local education to provide awareness of Addison’s disease diagnosis and treatment for healthcare practitioners including medical practitioners, nurse practitioners, and nurses in primary and secondary care settings.

-

Local protocol development for the management of adrenal crises in emergency departments.

-

Regular group education sessions for newly diagnosed patients and those that have lived with Addison’s disease for many years.

-

Further research into the patient experience and recognition of adrenal crises to understand if the patient experiences collected in this study translates nationally and internationally. This should include participants representing Māori and other ethnicities within Aotearoa New Zealand to ensure broader representation of the patient experience.

-

Development of an Aotearoa New Zealand based Addison’s disease patient support group.

CONCLUSION

This enquiry brings a new understanding of the patient experience when diagnosed and living with Addison’s disease. It has outlined how the knowledge around Addison’s disease and adrenal crises will influence and improve care to the patient journey of someone diagnosed with Addison’s disease in the future. It is evident that education for both healthcare practitioners and patients are key to aid in the prevention and treatment of adrenal crises. Having resources, such as a hospital specific clinical guideline, would be useful to provide support to attending clinicians whilst providing a level of confidence for patients that they will receive the right care at the right time. The development of a support group and education programmes could improve patient’s self-management abilities and reduce adrenal crises and hospitalisations by giving patients and their families the confidence to understand and manage their primary adrenal insufficiency.

Conflict of interests

None

Funding

None

Acknowledgements

Thank you to those participants who generously gave their time and knowledge to this study.