INTRODUCTION

A global nursing shortage of 7.6 million nurses and midwives is forecast by 2030 (Marć et al., 2019; World Health Organization, 2016). The recruitment and retention of new nurses is, therefore, crucial to maintaining the health workforce (Haddad et al., 2022). However, adverse work experiences, such as inadequate work environments, burnout, and a low sense of wellbeing, are causing nurses to leave their profession in high numbers (Flinkman & Salanterä, 2015; Heinen et al., 2013). One population of nurses exhibiting particularly high career attrition rates is early-career nurses (Flinkman & Salanterä, 2015). The term early-career nurse is variably defined in the literature but usually refers to nurses in their first five years of practice (Mills et al., 2017). Internationally, early-career nurses demonstrate high rates of both role turnover and career attrition compared to more experienced nurse populations (Mills et al., 2017).

There is growing research investigating mechanisms by which healthcare organisations can improve staff retention by implementing organisational wellness strategies. The concept of improving overall organisational wellbeing is referred to as positive organisational scholarship and focuses on improving positive attributes and outcomes of organisations and their employees (Cameron & Dutton, 2003; Kelly & Cameron, 2017). The Social Embeddedness of Thriving at Work Model (Figure 1) is one such model of positive organisational scholarship. In this model, thriving is described as “the psychological state in which individuals experience both a sense of vitality and a sense of learning at work” (Spreitzer et al., 2005, p. 538). Vitality, the first factor thought to influence thriving, is a combination of positive feelings, positive experiences, engagement, and enthusiasm (Porath et al., 2012). It is theorised that when individuals experience vitality, they become energised and are more likely to be engaged and motivated at work (Carmeli & Spreitzer, 2009). The sectond factor influencing individuals’ experience of thriving is a continual sense of learning, which refers to the ongoing acquisition of knowledge and skills as part of one’s everyday role (Spreitzer et al., 2005).

Thriving at work has numerous benefits for healthcare professionals, organisations, and consumers. For healthcare professionals, thriving at work has been linked with the experience of positive health outcomes (Spreitzer et al., 2005). For example, experiencing thriving in the workplace is associated with increased engagement among nurses (Moloney et al., 2020), which is an important factor in reducing nurse burnout (Dall’Ora et al., 2020; Van Bogaert et al., 2017). Reducing rates of nurse burnout is a key factor in improving retention in the nursing profession (Heinen et al., 2013). For organisations, a thriving workforce is beneficial because nurses who thrive are more likely to display positive agentic work behaviours (Spreitzer et al., 2005) that include an increased task focus, improved ability to explore new ideas or solutions, and heedful relationships with colleagues. Heedful relating occurs when mindful interactions between individuals demonstrate an understanding of how their roles merge with other employees’ roles to achieve the system’s overall goals (Spreitzer et al., 2005). These agentic work behaviours also impact positively on consumers with increased nurse-consumer relationships and higher focus on quality care (Moloney et al., 2020). In summary, nurses are thought to perform better when they are thriving, with thriving nurses creating a workforce of highly engaged, motivated, and focused nurses, which benefits healthcare organisations and consumers. Thriving at work is, therefore, an ideal concept from which to explore the issue of early-career nurse retention.

An Aotearoa New Zealand Context

Currently, limited research explores the experience of early-career nurses thriving in Aotearoa New Zealand. However, it is important to include an Aotearoa New Zealand perspective on thriving as the structure of the healthcare system and the uniqueness of the nursing workforce may mean international data does not represent the views of nurses in this country. Like many countries, Aotearoa New Zealand, has a nursing workforce shortage (New Zealand Nurses Organisation, 2018). Compared to other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries Aotearoa New Zealand has the highest reliance on migrant nurses (OECD, 2021). Recent immigration drives have seen growth in the overall nursing workforce and the proportion of internationally qualified nurses increase from 27% in 2020 to 41.7% at the end of 2023 (Chalmers, 2020; Nursing Council of New Zealand, 2023). This situation raises serious concerns about the nation’s ability to educate, recruit and retain domestically-grown nurses, particularly if we are to address nursing workforce inequities (Chalmers, 2020).

Current workforce statistics indicate inequitable workforce representation of Māori and Pacific nurses, with only 7.3% of nurses identifying as Māori and 3.6% identifying as Pacific (Te Whatu Ora – Health New Zealand, 2023). These workforce rates are significantly lower than the Māori and Pacific populations (national population rates of 19.6% Māori and 8.9% Pacific people) (Stats New Zealand, 2024). Addressing the underrepresentation of the Indigenous healthcare workforce has been identified as a critical factor in improving Indigenous health inequities (Curtis et al., 2012). It is, therefore, important that Māori and Pacific early-career nurses are supported and retained in the workplace to achieve health equity. To achieve Indigenous nurse retention, we must understand Māori and Pacific nurse employment experiences, including their experiences of thriving in the workplace.

Furthermore, Aotearoa New Zealand has high nurse burnout rates (Frey et al., 2018; Moloney, Gorman, et al., 2018; Nicholls et al., 2021). As burnout is associated with nurse attrition (Heinen et al., 2013), it is important to understand the factors affecting nurse workplace experiences in Aotearoa New Zealand. This study has explored the experiences of early-career nurses in Aotearoa New Zealand to identify factors affecting their workplace thriving.

METHOD

This study utilised a qualitative descriptive design (Colorafi & Evans, 2016) to explore factors that influenced the ability of early-career nurses to thrive in the workplace. Thriving was defined as experiencing both a sense of vitality and ongoing learning (Spreitzer et al., 2005). This model of thriving was selected as it has been widely demonstrated in literature to be applicable to healthcare settings (Jackson, 2022).

Participant Recruitment

Early-career nurses from one urban New Zealand hospital were recruited via emailed flyers inviting all early-career nurses employed at the study site to participate. Contact details for early-career nurses were identified through the organisation’s nursing development unit. Study invites were emailed to potential participants by the nursing development unit on behalf of the researchers in two stages: an initial invitation and a follow-up email three weeks later. Inclusion criteria required participants to be a registered nurse within the first five years of their nursing career and work as a registered nurse at the study site (a large tertiary hospital in Auckland, New Zealand).

Sample size estimation was guided by the theory of information power (Malterud et al., 2015). Information power is based on the principle that sample size should be determined based on the information that the sample holds. Assessing the required sample size can be achieved by considering five study domains: the aim of the study, sample specificity, use of established theory, quality of dialogue, and analysis strategy. The aim of this study is reasonably broad and focused on identifying factors which contribute to early-career nurses thriving at work. However, it is very specific to a particular participant group. The quality of data was expected to be strong with skilled facilitation of the interviews. Further, participants were expected to be engaged in the topic as we followed an appreciative inquiry framework known to uphold participant enthusiasm and engagement (Trajkovski et al., 2013). For these reasons, a small sample size of eight to 15 early-career nurses was estimated to be needed to provide high information power.

Data Collection

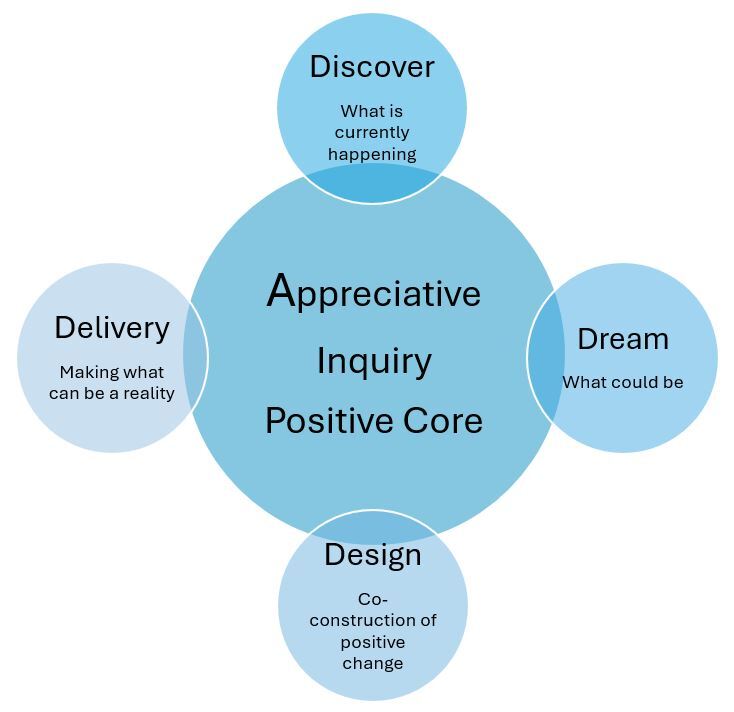

Data was collected by one author (ES) through individual semi-structured interviews. Interviews were conducted in-person, and online via the software conferencing system Zoom. All interviews were recorded and the audio recording saved and transcribed. Participants were given the option to receive a written transcript of the dialogue for respondent validation. Interview questions (Supplementary File 1) were formulated based on findings from a literature review and guided by elements in the Thriving at Work Model (Spreitzer et al., 2005, Figure 1). Researchers also utilised the appreciative inquiry framework (Figure 2), developed from the work of Stavros et al. (2015) to develop the interview guide as it is an established model of promoting positive organisational change.

Appreciative inquiry is a positivity-based research approach utilised in implementing changes in organisations or systems, whereby researchers conduct a positivity-based exploration of future possibilities or improvements (Hung et al., 2018; Trajkovski et al., 2013). Using appreciative inquiry to focus on organisational leadership as a collective, rather than the behaviours of individual leaders, enables blame-free exploration of an organisation’s success so that challenges are permitted (Schall et al., 2004; Trajkovski et al., 2013). Elements of the appreciative inquiry model shown in Figure 2 were incorporated into the interview guide, with interview questions presented using a positivity-based exploration to support participant positivity and engagement in the organisational change process (Hung et al., 2018).

Data Analysis

Data analysis was completed using Braun and Clarke’s (2022) reflexive thematic analysis. Coding followed a process of both inductive and deductive coding. Deductive coding was informed by the nomological framework developed by Kleine et al. (2019) from reviewing existing research on the factors that influence thriving. Data analysis was completed by one reviewer (ES) with collaboration of author (SJ) and followed the six-stages of reflexive thematic analysis as outlined by Braun et al. (2019). Data familiarisation was achieved through the principal investigator conducting all interviews and conducting manual transcription. Initial themes were constructed from these codes by author ES, followed by revision and further development and definition of themes through a process of collaborative discussion by both authors (ES, SJ). Finally, the written analysis was completed by author ES and reviewed by the second (SJ).

Ethical Considerations

Te Tiriti o Waitangi (The Treaty of Waitangi) is the founding document of Aotearoa New Zealand and outlines the relationship between Māori and the Crown. Te Tiriti o Waitangi underpins all aspects of Aotearoa New Zealand society, including academic research (M. L. Hudson & Russell, 2009). To ensure responsiveness to Māori, Māori were present in this study as researchers, advisors, and participants. To ensure cultural safety for Māori in this study, principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi and Te Ara Tika Guidelines (Table 1) informed study design (M. Hudson et al., 2010).

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the relevant health research ethics committee in October 2020 (AH2621). Prior to the commencement of the interviews, participants were provided with a participant information sheet and a consent form, which they were required to sign before the interview could begin. Participants were able to refuse to answer any question or withdraw consent to participate at any point during the interview and could withdraw their data from the study for a period of two weeks following the interview.

FINDINGS

Participant Response

Nine early-career nurses were included in this study. Participants were from various nursing specialities and ranged in age and level of experience (Table 2). Study participants all identified as female and were aged between 18-34 years old. Four participants were in their first one-two years of practice, three had three to four years of practice experience, and two had four to five years of practice experience.

Reflexive thematic analysis of interviews identified four major themes: interpersonal relationships, work environments, positive meaning, and ongoing learning and development. Table 3 provides a description of the identified themes and sub-categories.

Interpersonal Relationships

Early-career nurses identified that positive interpersonal relationships with colleagues greatly influenced overall workplace experience. A prominent sub-theme of this category was ‘ward culture’ – referring to the overall social atmosphere of workplaces. Early-career nurses identified that workplaces that promoted a positive ward culture resulted in feelings of improved teamwork, respect, and friendship amongst colleagues.

As a bedside nurse, I worked with some good, good, friends so that was good because I could turn to them… I enjoyed the team I was with, both nursing staff, health care assistants, orderlies, reception staff, doctors; they were all really cool people, and we did lots of social gatherings outside of work which was nice to connect with. [Nurse 8]

Being part of a work environment that promoted positive interpersonal relationships was also highlighted to improve teamwork, thereby reducing workload. This was suggested to have an impact on patient care.

A team really does make the shift. When you don’t have everyone working together, or if people are only working to make themselves succeed and not supporting everyone else it makes the day a struggle and harder, and you feel like patients don’t have the best care… When everyone is working together, the patient gets a better experience, and your workload actually decreases if everyone is chipping in. [Nurse 4]

Not all early-career nurses reported working in environments where good interpersonal relationships were fostered. Some early-career nurses described environments where overall teamwork and support was lacking. Participants also relayed that some ward cultures allowed for the exclusion and bullying of nurses to occur.

It’s average [the ward culture] … I totally walked into my first role thinking that I was going to be supported, that there was going to be good communication, that there was going to be a good team environment. I was very näive because I walked in totally relating to my colleagues on that assumption, only in my first year to get quite burnt. [Nurse 9]

Participants who experienced bullying explained that bullying affected all aspects of their careers. In some cases, nurses were left feeling like they did not want to come to work or expressed a desire to leave the nursing profession. When questioned, some participants also raised concerns that bullying in their workplace was targeted at early-career nurses.

I think so [bullying problem in my organisation]. On my old ward, there was a set few that had been there for a very, very long time, and then you had the new graduates coming in who were turnover heavy [only lasting for] 1-2 years, and I feel like they were not retaining any new nurses. There were only the old nurses who were really set in their ways. They [the organisation] need to really focus on bullying. [Nurse 3]

Relationships with charge nurses were highlighted to be a prominent factor in early-career nurse experiences. Feeling supported by charge nurses and other ward leaders was identified to strongly affect ward culture.

I think really a supportive charge nurse or manager and support of a great team. It makes the entire work environment a better place to grow to be honest. [Nurse 7]

I know nurses who dread coming to work because they don’t have a supportive environment. So, I think feeling well supported at work is definitely a key. I think feeling supported by your managers and your bosses is the key in terms of success or thriving. If you don’t want to come in because you are not managed properly [you will not thrive]. [Nurse 8]

Work Environment

The physical work environment greatly influenced early-career nurses’ ability to thrive. Several participants described experiencing unmanageable workloads that affected their ability to thrive. High workloads were reported to affect both patient care and early-career nurses’ physical needs, such as the ability to take breaks or sick leave.

You can feel like you don’t have enough time to take your breaks…. I think a good day here is if I have seen all my patients, written all my notes, and have had my lunch before I go home. [Nurse 8]

I wasn’t well, but we were short-staffed, and they said, “well you are just going to have to manage till lunchtime” and I fainted… I wasn’t feeling well, but you know you can’t really call in sick when you wake up not feeling well in the morning. You get that pressure that you have to come into work. [Nurse 3]

Participants theorised that lowering patient-to-nurse ratios would enhance rates of early-career nurses’ thriving and would result in better patient care. When asked about the one thing that could increase nurse wellbeing nurses spoke of reducing the nurse patient ratio:

The more patients you have, the less care they get… all that stuff contributes to their health and wellbeing. It also contributes to the nurses’ wellbeing because we are not stressed and feeling like we aren’t doing our jobs, feeling like we are not good nurses because we haven’t achieved what we wanted to in a shift. [Nurse 4]

Continued exposure to high workloads can lead to burnout. Most nurses interviewed identified that they had experienced or were currently experiencing burnout, describing physical and psychological exhaustion symptoms typical of burnout, such as feeling anxiety or dread about coming to work, mental unwellness, extreme fatigue, and emotional lability. Burnout was a reason some had left previous nursing positions:

Sometimes there are times when you have had a stressful run of shifts where you get pre-work anxiety. There is all this anticipation of what might happen… There were times in the first couple of years where I would get so anxious that I wouldn’t want to come to work because I was feeling burnt out. [Nurse 5]

Shiftwork also played an important role in thriving in the workplace for early-career nurses, with all participants reporting working some degree of shiftwork in their roles. Participants reported varying experiences of shiftwork depending on their employment status (full-time/part-time) and control over their work schedule. Negative experiences of shiftwork largely revolved around the physical impact shiftwork had on early-career nurses’ personal lives.

[You feel] like you kind of don’t do as much outside of work because you are constantly tired, or you are mindful that you need to conserve energy for a shift. You are constantly feeling like you have to prioritise work over personal things, and that sometimes was challenging because you want to be able to enjoy your personal life and enjoy other things, but you are too exhausted. [Nurse 5]

However, participants also reported enjoyment in the flexibility that shiftwork permitted, particularly when they were able to self-roster shifts. Having the flexibility to work variable shift lengths, e.g. eight-hour or twelve-hour shifts was also important to early-career nurses, with some participants reporting limited autonomy in shift length as a reason they planned on leaving their current role:

There are some really good benefits [to shift work]. You can get tasks done on a weekday like book appointments, and that’s really convenient… If I want a four day weekend I can just work my shifts around so I have a four day weekend. [Nurse 4]

I am hoping to find a new job [in nursing] that [permits 12-hour shifts] so that in my spare time, on my days off, I can learn some new skills and potentially look into a different industry… I think, personally, the impact on my health means I can’t see myself doing shift work for life. [Nurse 7]

Another aspect of the work environment highlighted by early-career nurses as influencing perceptions of thriving was remuneration packages. Participants did not feel their wages reflected the level of work, skill, and responsibility that being a nurse required. Pay was highlighted by early-career nurses to be a significant factor affecting their long-term retention in the nursing career. One early-career nurse expressed that if they had the chance to retrain, they would not become a nurse because of poor pay.

I am going to potentially look into a different industry… I think it is just the salary. It just doesn’t match up to our living costs, and compared to my other friends who are outside the healthcare industry, [the salary] it doesn’t grow as fast. [Nurse 7]

The lack of financial incentive to complete further post-graduate education was an issue. Participants felt this did not match other careers where increased qualifications would typically result in an increased salary:

You don’t get any more money for progressing your education or improving your care. So finishing your diploma, I will have the same pay as a nurse who hasn’t done it. So why would I take on the extra debt or progress further if I am not going to get paid to reflect that? In any other workforce, if you were to go and get extra training, you would be able to argue for extra pay. [Nurse 4]

Finding Positive Meaning

Early-career nurses highlighted that providing care to their patients was a meaningful experience and improved day-to-day job satisfaction:

I think, for me, one of the key things that makes a good day for me is feeling like I am able to care for my patients and give them the best care they feel they deserve. [Nurse 9]

[A good day] is being able to be with patients and see them be comforted and find that they have gone through their care in a positive way. [Nurse 2]

Finding positive meaning in their roles also acted as a protective factor for career retention, with several early-career nurses reporting that caring was central to their career identity.

I thought about what else I could do, there is a lot out there, but I don’t think I would get the job satisfaction that I get as a nurse. I enjoy helping people when they are at their most vulnerable. [Nurse 9]

I think what makes me proud working as a nurse is supporting people when they are at their most vulnerable time. [Nurse 8]

Conversely, when early-career nurses’ ability to care was affected by high workloads, job satisfaction decreased:

If I am unable to do that [care for patients well], you start feeling inadequate because you just see all the things you are meant to be doing. You have to prioritise to a certain extent, but some days it goes a bit beyond that…. You just feel overwhelmed, and then you feel inadequate, and then you feel like you have to apologise to your patients all the time because you feel like you’re not doing all the things you would like to be doing for them. [Nurse 9]

Self-care was highlighted as a technique many early-career nurses used to maintain positive meaning in the workplace. Participants used varying self-care strategies to mitigate work stressors, including taking annual leave, mindfulness, and accessing the free counselling service provided by the organisation.

I did actually do a mindfulness course that [the ward] offered, which I really enjoyed even though I am quite a mindful person already, but I really appreciated that they offered that. [Nurse 5]

Ongoing Learning and Development

Early-career nurses reported engaging in learning in their everyday roles. Learning was primarily reported as a positive factor in overall thriving in the workplace. Many early-career nurses highlighted that the majority of their learning is informal, based on doing rather than formal teaching and is guided by colleagues on the floor. One participant identified that continuous learning was a part of what they enjoyed about their work.

Yes definitely, which is usually a really good thing… mostly that’s part of what I really love about my job. [Nurse 1]

Many workplaces were regarded as supportive of ongoing learning, with ward leaders continuing ongoing education and offering learning opportunities encouraging participants to develop new skills.

I got only positive feedback about continuing my tertiary education. My charge nurse is really positive about that stuff, and I think she drives that, and she is really keen to get people doing the courses they want to and participate in research. [Nurse 2]

Continued access to learning was reported to affect role attrition. When early-career nurses reported role and learning stagnation, they indicated intention to leave:

I have thought about leaving [my current nursing role] to try different areas, partly because of the slow progression. I had a stage where I did not feel I was learning anything new. [Nurse 6]

High workloads were reported to be the largest barrier to engaging in ongoing learning. Time pressures and lack of access to senior nurses resulted in early-career nurses feeling pressured to learn new tasks independently and quickly:

There might be procedures and medications that you might not have done before, or you’ve been told about, but you’ve not actually gone through the motions. So you want someone to support you through that, and obviously, if there are times when it is quite junior-heavy, you feel a little bit compromised or a little bit stressed. [Nurse 5]

High workloads also affected how much time nurses were able to dedicate to learning during their workday. Similarly, to engage in ongoing professional development, nurses had to take leave, which was also impacted by staffing ratios:

[More staff] would be helpful because then you could take more days off to go to university, and you wouldn’t feel guilty because there is no staff. I think staffing is really huge. [Nurse 8]

DISCUSSION

Using a qualitative descriptive methodology this study interviewed nine Aotearoa New Zealand early-career nurses to establish what factors influenced their ability to thrive in the workplace. Four themes were identified as impacting thriving: interpersonal relationships, work environment, finding positive meaning, and ongoing learning and development.

Interpersonal relationships played an important role in facilitating thriving in the workplace. Where early-career nurses reported positive interprofessional relationships, satisfaction with ward culture and thriving in the workplace was high. This correlates with Spreitzer et al.'s (2005) model which shows that a workplace of trust and respect is vital to individual thriving. Aotearoa New Zealand and international literature also support a positive correlation between collegial relationships and job satisfaction within the nursing workforce (Waltz et al., 2020; Were, 2016). In contrast to this, early-career nurses who reported experiencing negative interpersonal relationships, such as poor teamwork, and bullying, typically expressed a poor ward culture and low job satisfaction. Concerningly, several participants reported experiencing bullying from senior nurses in the workplace. Hierarchical bullying of junior nurses is an established trend in international literature - a term coined ‘nurses eating their young’ (Dames, 2019; Daws et al., 2020). This qualitative study highlights that hierarchical bullying is also an issue for New Zealand early-career nurses.

The predominant factor identified in this study as negatively impacting the experience of thriving for Aotearoa New Zealand early-career nurses was the work environment. Many participants reported experiencing unmanageable workloads and inadequate staffing ratios for extended periods. Several authors have also described the high workloads experienced by nurses in Aotearoa New Zealand, highlighting that increased workloads are a widespread issue (Harvey et al., 2020; Moloney, Boxall, et al., 2018). High workloads impact early-career nurses’ ability to provide high-quality patient care, which is an important factor for experiencing thriving in the workplace (Dames, 2019). Providing high-quality care improves interactions between early-career nurses and patients, giving them an inherent sense of meaning in their jobs. Meaning in work has been defined as the presence of existential significance generated from one’s work experience, work itself or work purpose/goals (Lee, 2015). Finding positive meaning in their role is a protective factor for role and career retention for early-career nurses. National and international literature supports the importance of finding positive meaning, with several studies reporting on the positive effect caring has on nursing job satisfaction, retention, and identity (Amendolair, 2012; Harvey et al., 2020; Nasrabadi et al., 2015).

Participants in this study expressed dissatisfaction with remuneration in comparison to the perceived responsibility and effort required in their positions. In some instances, low pay affected thriving and increased thoughts of career attrition. While remuneration is not a consideration in the Thriving at Work Model (Spreitzer et al., 2005), this finding corroborates with international research, which shows that pay is a motivating factor for role and career retention for registered nurses (Steinmetz et al., 2014). In the context of a cost-of-living crisis, pay has been seen to be an important marker of job satisfaction across professions, meaning it is unsurprising that this was reported to be a significant issue for early-career nurses (Gutiérrez Banegas et al., 2022).

Early-career nurses in this study highlight that experiencing ongoing learning and career development opportunities influenced the experience of thriving and role retention. This finding is consistent with the Thriving at Work model which highlight that learning and career progression are important aspects of thriving at work (Spreitzer et al., 2005). Some participants reported they intended to leave roles to improve professional development and learning opportunities. This finding contrasts with a previous survey of nurses in Aotearoa, New Zealand, where professional development opportunities appeared not to affect the intention to leave (Moloney, Boxall, et al., 2018). Therefore, results from this study may indicate that early-career nurses value learning and career development more than a general population of New Zealand registered nurses.

Limitations

The study participant number was small, with only nine early-career nurses interviewed. Low numbers of participants were largely due to difficulty recruiting early-career nurses to take part in the study. We posit that the limitations of a small population have been mitigated by the rich, in-depth data we received during interviews, demonstrating the appropriate application of Malterud et al.'s (2015) theory of information power in our study design. A total of three (33% of participants) Māori early-career nurses participated in this study. This resulted in high Māori representation when compared to the population of Māori nurses in both Aotearoa New Zealand (7.9% of all registered nurses) and early-career nurses at the study site (8.56% of early-career nurses). However, due to the total participant number being small, this study still had too few Māori participants to reach sufficient information power and may not reflect the perspectives of all Māori early-career nurses. This study included early-career nurses at one tertiary urban hospital. More research is needed to explore the experiences of early-career nurses in similar tertiary settings as well as other hospital settings and work environments, such as primary healthcare and Māori health services. This study also only interviewed female early-career nurses, which limits our understanding of the perspectives of male early-career nurses. The lack of male participants is hypothesised to have occurred because of the low number of male early-career nurses (8%) at the study site. More study advertising aimed at male early-career nurses may be needed to represent all early-career nurses effectively in future research.

CONCLUSION

This qualitative study provides an important insight into thriving in the workplace for the under-reported population of early-career nurses within Aotearoa New Zealand. Several factors affect the ability of early-career nurses to thrive in the workplace, which has implications for both job satisfaction and nurse retention. Interpersonal relationships, work environments, finding positive meaning, and engaging in ongoing learning and development have positive and negative implications for early-career nurses thriving in the workplace. Poor work environments were reported to be the largest negative factor affecting early-career nurses’ ability to thrive.

Findings from this study highlight that models of organisational scholarship, such as Spreitzer Thriving at Work Model, can provide nurse leaders and managers key information and processes as they seek to improve thriving in the healthcare setting. Early-career nurses experiences of thriving corroborate elements of the Thriving at Work Model, highlighting mindful and heedful relating, which generates positive meaning, are important precursors to thriving. Opportunities for improving early career thriving in the workplace largely relate to managing workload and establishing positive relationships as these affect multiple domains of the Thriving at Work Model including learning and development, heedful relating, and the ability to focus on individual tasks and patient needs. While more research needs to be done in the Aotearoa New Zealand context, this study has demonstrated that applying models of organisational scholarship presents an opportunity for healthcare organisations to improve the workplace, allowing Aotearoa New Zealand early-career nurses to thrive.

Funding

None. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.