Journal of Professional Nursing

Introduction

In November 1985, Nursing Praxis in New Zealand was launched as the first peer-reviewed nursing journal to be circulated in Aotearoa New Zealand. In 2020 we were proud to celebrate 35 years of continuous publication and renamed the Journal to Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, acknowledging our country’s bicultural partnership under Te Tiriti o Waitangi and our commitment to tangata whenua (Māori, the Indigenous people of the land). This milestone coincided with the 2020 International Year of the Nurse and Midwife, celebrating the 200th anniversary of Florence Nightingale's birth, though was soon overtaken by the COVID-19 pandemic.

As this Special Issue is released, we acknowledge that the pandemic is far from over and our overseas peers continue to face enormous challenges in harrowing circumstances. Globally, the daily recorded cases of COVID-19 are the highest yet. The poorest of those communities have suffered the greatest losses and are now faced with the inequitable distribution of vaccines. We can only begin to imagine the long-term impacts of COVID-19 on the health and wellbeing of individuals and communities and the health requirements of the future. Health workers are exhausted and health services stretched beyond capacity. COVID-19 reported deaths are estimated to be 17,000 health workers (Amnesty International, 2021) and 2,710 nurses (International Council of Nurses, 2021). These figures are likely to be considerably underreported and rising. The World Health Organization designated 2021 to be the International Year of Health and Care Workers “in appreciation and gratitude for their unwavering dedication" (para 1).

This Special Issue celebrates nursing and challenges nurses to continue their work to deliver healthcare and promote equity for all communities. Nurses: A Voice to Lead - A Vision for Future Healthcare is this year's theme for International Nurses' Day on 12th May 2021, acknowledging the essential work of nurses through the pandemic. While here, in Aotearoa New Zealand, we have had relatively few cases of COVID-19 cases per se (2,600 to date), we know many of our whānau and communities have been adversely affected through loss of jobs, income, and schooling; separation; and isolation. The impact on mental health will be far-reaching. Through these times, nurses have shown resilience and creativity, to promote health and protect their communities. Amidst the rollout of the COVID-19 vaccination programme, we embark on the implementation of the recently announced Health Reform White Paper (Health and Disability Review Transition Unit, 2021). Now more than ever, we need nurses to bring the breadth and depth of their knowledge and skills to be fully engaged, advocating for, and leading the development of future, equitable health services for the communities they serve.

This Special Issue honours the investment made to the scholarship of nursing in Aotearoa through this Journal, by its instigators, contributors, reviewers, and Editorial Board members since its inception.

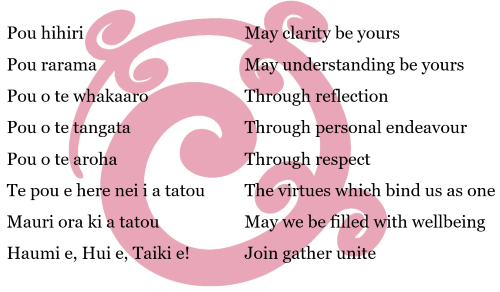

Karakia / Blessing

Approach to the Special Issue

This issue looks 'back to the future'. Following a review of the back issues, articles from three authors were selected to represent what we, the Editorial Board, believe signal topics central to nursing’s mahi (work) towards health and wellbeing, and health equity in Aotearoa. We asked a range of thought-leaders in nursing to reflect on the articles, to consider the contribution they have made, and to comment on their continued relevance for contemporary nursing practice. Each thought leader was given a mandate for incisive and inspirational commentary, identifying practical and concrete steps that nursing and nurses could take across education, practice, research, scholarship, policy, and service provision. Additionally, we provide a synopsis of each article together with the article's connection to the contemporary context.

The Special Issue opens with an editorial from Margareth Broodkoorn, previous Chief Nursing Officer at the Ministry of Health (2019-2021). Following the editorial, Dr Martin Woods provides an introduction to the articles. The work of the three authors is then presented in sections. Each section includes a synopsis of the article and its contemporary context, as well as links to the original article(s). Thought leaders provide kōrero (commentaries) in each of the sections. The issue concludes with a final critique from Professor Jenny Carryer CNZM.

Links (highlighted in red) allow you to move up and down the page; to salient online reports and to previous Nursing Praxis articles, which open in a different tab. We invite you to provide any comments, critiques, or reflection at the end of this page/issue.

An overview of contents

Editorial and Introduction by Margareth Broodkoorn and Dr Martin Woods

Section 1: Jocelyn Keith's prescient question about the human right to health and healthcare

With commentaries by Professor Stephen Neville, Dr Catherine Cook, and Marie-Lyne Bournival

Section 2: Dr Irihapeti Ramsden's powerful petition for cultural safety: Kawa Whakaruruhau

With commentaries by Professor Denise Wilson, Hemaima Hughes, Dr Jennifer Roberts, and Dr Fran Richardson

Section 3: Dr Jill Wilkinson's discourse analysis of the sources of power and agency for nursing

With commentaries by Dr Joy Ashley Bickley, Dr Helen Rook, Dr Rhonda McKelvie, and Dr Sue Adams

A final critique by Professor Jenny Carryer

Acknowledgements, references, and an opportunity to provide comments, are provided at the end of the page.

Note: Te reo Māori (the Māori language): Nursing Praxis encourages the use te reo Māori terms where appropriate. Many concepts in te reo do not have a direct translation into English, because often they are concepts that are culturally located. Please see the glossary on our website for further information: Māori Research and Te Reo.

We very much hope you enjoy reading this issue and that it offers the opportunity for reflection and dialogue for nursing students and nurses in all scopes at all stages of their career.

Ngā manaakitanga

Sue Adams PhD RN & Caz Hales PhD RN

Editors-in-Chief

Citation: Adams, S., & Hales, C. (2021). Special issue to celebrate 35 years of publication of Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand: Introduction. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 37(1), 5-8. https://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2021.018

| Introduction | Introduction to the Special Issue |

| Editorials | |

| Margareth Broodkorn | Tai timu tai pari: Nursing’s role in health transformation |

| Martin Woods | Nursing's essence and the health care needs of humanity |

| SECTION 1 | Jocelyn Keith's prescient question about the human right to health and healthcare |

| (Sue Adams, Catherine Cook, Shelley Jones) | |

| Commentaries | |

| Stephen Neville | The right to health: Discrimination and our responsibilities |

| Catherine Cook | Widening the lens of evidence-based healthcare |

| Marie-Lyne Bournival | The human right to healthcare and the nurse practitioner role |

| SECTION 2 | Dr Irihapeti Ramsden's powerful petition for cultural safety: Kawa Whakaruruhau |

| (Kiri Hunter, Jennifer Roberts, Mandie Foster, Shelley Jones) | |

| Commentaries | |

| Denise Wilson | Naku rourou, nau rourou, ka ora ai te iwi |

| Hemaima Hughes | Te hikoi o Kawa Whakaruruhau inanahi ki aianei: The journey to cultural safety yesterday to today |

| Jennifer Roberts | Challenging the status quo: Raising cultural safety, again |

| Fran Richardson | Moving on: From debate to deeper conversations |

| SECTION 3 | Dr Jill Wilkinson's discourse analysis of the sources of power and agency for nursing |

| (Helen Rook, Caz Hales, Kaye Milligan, Shelley Jones) | |

| Commentaries | |

| Joy Bickley Asher | He waka eke noa: We are all in this together |

| Helen Rook | Rising above polarising discourses within nursing |

| Rhonda McKelvie | Pushing the boundaries: Consciousness and concerted action in times of quantum change |

| Sue Adams | Politics and paradigms in healthcare: Challenging the status quo |

| A Final Critique | |

| Jenny Carryer CNZM | The need to release the potential of nursing has never been greater |

| Acknowledgements | |

| References | |

| Comments | Leave a comment |

2020 marked 35 years of the first peer-reviewed nursing journal - now named Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, reflecting biculturalism and the intent to promote the work of Māori authors and research – an important milestone for nursing. In this special edition of Nursing Praxis contemporary perspectives have been sought on the writings of three nursing scholars (Jocelyn Keith, Irihapeti Ramsden, and Jill Wilkinson) and the respective themes from these articles.

When reading these articles (published between 1987 and 2008) one might sense some relevance of their kōrero to the current day. Sadly, the familiarity of these writings probably reflects the lack of progress in thinking, actions, and outcomes of the past 35 years.

I, like many of my colleagues, would rather not experience these déjà vu moments. However, after 35 years as a health professional I am gaining confidence that the tide is turning. In te ao Māori, this movement is referred to as "tai timu tai pari", reflecting the tidal ebb and flow. This analogy is relevant to the impending changes in the health system. The question is, what role will nursing play in this sea change or transformation?

We knew 2020 would be a big year, as we planned to celebrate International Year of the Nurse we were diverted to another priority. While COVID-19 changed our lives forever, it also set the context for healthcare to be critically re-examined. When honouring colleagues who have died from COVID-19, we also recognised how the critical role of nursing was brought sharply into focus by working collaboratively and where previous system barriers were annihilated.

Nursing was at the forefront of a significant health response; not due to being the largest health workforce, but by demonstrating the utility, flexibility, and moral imperative of a profession committed to the wellbeing of communities. Lessons learnt regarding collaboration and speaking with one voice will hold nursing in a strong position within any future system changes.

The first State of the World’s Nursing report (World Health Organization, 2020) was published in April 2020. New Zealand’s nursing profile compared well to other countries. However, on reviewing the Report’s ten key actions, Aotearoa needs to make improvements in several of these policy areas. These include continued investment in nursing; monitoring international nurse mobility focussing on the domestic production of nurses; nurturing young leaders; safe staffing; addressing the gender gap; and collaboration across systems. Further implications of the State of the World's Nursing report require nursing policy to align with the Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, 2015) by eradicating poverty, ensuring inclusive and equitable education; and achieving universal health coverage requiring access to quality care which is fundamental to population heath and health equity.

In April 2021, the Minister of Health, Andrew Little, released a White Paper for Health Reform based upon the 2020 Health & Disability System Review which identified 86 significant changes required to the systems structure, leadership, and funding. The Health Reforms are perhaps more far-reaching than was anticipated, including replacing the 20 district health boards with a single organisation, Health NZ, and four regional entities; and a new Public Health Authority to centralise public health work. Perhaps most significant is the establishment of a Māori Health Authority in recognition of the government’s obligations to Māori under Te Tiriti o Waitangi to support hauora Māori and promote equity. At a locality level, emphasis is placed on Te Tiriti partnerships with local iwi and Māori to shape health service design and delivery. Prior to the Review and White Paper, the Ministry of Health (MoH) placed a strong mark on the health landscape by providing a robust definition of equity. Whakamaua: Māori Health Action Plan 2020-2025 articulated how to give effect to He Korowai Oranga (MoH, 2020) by providing a Te Tiriti o Waitangi framework.

The commitments articulated in 2021 and by the aforementioned documents provide an enduring platform on which system reform is to occur and where nursing has a key role to play.

System change is already happening. For the first time in 2020 a nurse faced professional misconduct charges for online racist remarks. This incident raised concerns about the efficacy of cultural safety education and the need to address the rhetoric and racism (Manchester, 2020). There remains a fundamental issue of the ‘watering down’ of Kawa Whakaruruhau with the simplification of ‘taking your shoes off at the front door’. A move from transactional tick box interactions to meaningful interventions requires further critical analysis of the power dynamics within nursing.

The National Nursing Leadership group (NNLg) is reflecting a more meaningful approach in committing to a Te Tiriti governance model. This leadership forum is a collective of nursing leaders who represent education, professional organisations, employers, the regulator (Nursing Council of New Zealand), and the MoH. Each member group is committed to attending meetings with their Te Tiriti partner, including Pacifica representation. Further, the NNLg are leading the development of a national nursing strategy that articulates the future of nursing and encapsulates the aspirations of the three nursing scholars featured in this special Nursing Praxis edition.

The tide is definitely turning. Having ended my time as Chief Nursing Officer at the MoH and as I now embark on a new journey as CEO for a Māori health provider, I welcome a new Chief Nurse who is Māori. This is another significant system change by having a Māori nurse at the decision-making table. Nau mai haere mai Lorraine Hetaraka. Nursing is well placed to lead system change and be at the forefront of innovation, the time is now with a permissive environment and commitment to Te Tiriti and addressing inequities.

Citation: Broodkoorn, M. (2021). Tai timu tai pari: Nursing's role in health transformation. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 37(1), 9-11. https://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2021.001

Nursing, like life itself, should be positioned within an underlying philosophy, which for me, has always commenced with the ‘spirit’ or ‘essence’ that motivates all nursing actions. This ‘essence’ is first and foremost a moral one where nurses everywhere are charged with the task of meeting the care-based health needs of humankind in an ethically mindful fashion.

This phenomenon is to be found in various guises in all four articles nominated for this special retrospective review of Nursing Praxis articles over the last thirty-five years. In Jocelyn Keith’s (1987) case, this essential meaning is founded in the power of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, 1948) and developed in the socially mindful responses of nurses. However, being ‘socially aware’ has several possible meanings, and over the years, nurses have often found it difficult to turn this awareness into entirely satisfactory responses. For instance, in Irihapeti Ramsden’s (1990) eyes, this awareness within the ‘spirit’ of nursing is reflected not just by reference to Nightingale’s morality and role modelling, but to human decency which is accurately focussed on offering true cultural respect towards others in our care. At times, this task remains a difficult one for nurses within a healthcare system that still struggles to recognise that nurses sometimes practice within an ethical climate that does not always fully support such necessary vigilance. Jill Wilkinson’s (2008a, 2008b) articles extend both of these major concepts by strongly suggesting that nurses must continue to strive for social justice, a major moral imperative, through individual and collective actions. Such actions, be they supported by either the professional or the ‘unionised’ wings of the profession, should therefore remain a necessary focus of any nursing organisation in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Hence, if we are ever going to be able to claim that nurses fully contribute to the healthcare needs of humanity in truly meaningful ways, we should therefore begin with a re-examination of our philosophical roots, and especially the ongoing necessity for the use of our own pragmatic but heavily socially aware care-focussed ethics, before acting accordingly. Curiously enough, Nightingale’s emphasis on united and unified moral and practical responses within a strong public health agenda, and her advocacy for evidence-informed public policy, is as relevant now (and especially now in this time of the next great pandemic) as it was in her time.

Citation: Woods, M. (2021). Nursing's essence and the health care needs of humanity. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 37(1), 12-13. https://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2021.002

[Back to Top] [Contents]

| Sue Adams, PhD RN, Senior Lecturer, School of Nursing, University of Auckland/Te Whare Wānanga o Tāmaki Makaurau, Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand |

| Catherine Cook, PhD RN, Senior Lecturer, Auckland University of Technology, Aotearoa New Zealand |

| Shelley Jones, RN BA MPhil, Independent Professional Nurse Advisor, Aotearoa New Zealand |

| Commentaries | |

| Stephen Neville | The right to health: Discrimination and our responsibilities |

| Catherine Cook | Widening the lens of evidence-based healthcare |

| Marie-Lyne Bournival | The human right to healthcare and the nurse practitioner role |

Article

Keith, J. (1987). The right to health or the right to health care. Nursing Praxis in New Zealand, 2(3), 18-24. https://doi.org/10.36951/NgPxNZ.1987.008

![]() Keith 1987

Keith 1987

Synopsis

In January 1987, Jocelyn Keith (now Lady Keith CBE) was a lecturer in the Department of Community Health at the Wellington School of Medicine and presented a paper at the conference of the Australian and New Zealand Association for the Advancement of Science. An introduction to "The right to health or the right to health care," as it was published in the July 1987 issue of Nursing Praxis, sets up a complex problem: What constitutes appropriate healthcare to protect the right to health and wellbeing, in the light of New Zealand's obligations as a signatory to international declarations and covenants; and our Government's obligations to honour Te Tiriti? The forum where the paper was first presented determines Keith’s lens. She argues, with reference to contemporary cost-benefit studies, that science advances both high-tech procedures (example: heart transplant) and public health programmes (example: Hepatitis B vaccination). Both are developments that respond to "ever-rising expectations of prolonged life and health" (p. 20); and both programmes cost similar amounts. One programme will directly benefit a very small number of people (n=12), while the other programme reaches a large number of newborns (n=20,000) on the basis of preventing future ill health for a relatively small number. Public health science is constantly needing to seek ways of managing health need. Further, she makes an argument for an evidence-based direction: “The escalating cost of the aggregation of individual decisions within the health system makes it imperative that science address the urgent need for information about the link between health status and health service" (p. 20). Yet the notion of health conjures up visions of high-tech hospitals delivering complex interventions to provide healthcare, often with inadequate attention to primary health care and public health sciences where the focus is on health promotion and illness prevention.

Standout paragraph (Keith, 1987, p. 22)

The article in context:

Jocelyn Keith argued for a framework to enact the internationally agreed vision of the right to health and wellbeing with the pragmatic delivery of healthcare that honours Te Tiriti. There are several developments to add to Keith’s 1987 outline of the history of human rights in relation to health, including the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2006 and the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) 17 Sustainable Development Goals (2015) describe that ending poverty and other deprivations must go hand-in-hand with strategies that improve health and education, reduce inequality, and spur economic growth – all while tackling climate change and working to preserve our oceans and forests. An example of the need to reconcile commitment to internationally agreed aspirations with pressing concerns particular to Aotearoa is the State of the World’s Nursing Report 2020. The report recognises the central role of nurses in achieving universal health coverage and Goal 3 - good health and wellbeing - yet is all but silent on the promotion of an Indigenous workforce (Chalmers, 2020).

We are familiar with the WHO's founding principle that defines health as "a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity" (WHO, 2021, para 1). But there's a question implied in the title of Keith’s paper: Is it "the right to health" or "the right to health care"? The commonly used term the right to health includes the right to healthcare, and the right to the underlying preconditions for health, including access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation, healthy houses and environments, safe workplaces, and health-related information. Even so, the right to health does not guarantee an individual's optimal health (Hunt, 2016; Toebes, 1999). Keith argues that "the right to health care" must be understood within the bounds of what signatory nations can resource and choose to prioritise.

We are also familiar with the WHO principle that the right to health applies to all, equally and without discrimination, as "one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition" (WHO, 2021, para 2). But these distinctions account for the relative social advantages or disadvantages which determine the health gap between those with better or poorer outcomes (Marmot, 2017). The right to health therefore includes the broader socio-economic determinants of health.

In the decades since Nursing Praxis published an analysis of racism in health service structures (Bickley, 1987) there has been no shortage of evidence and argument about inequality in Aotearoa New Zealand. Evidence of the statistical trends in Māori health over the years 1990–2015 (Ministry of Health, 2019), was prepared specifically for the Waitangi Tribunal’s Health Services and Outcomes Inquiry (2019). The Tribunal found that the primary health care sector had failed to achieve Māori health equity, and as such, Te Tiriti had been breached. The need to recognise racism’s negative impacts on health and wellbeing (Harris et al, 2018) was rendered vividly apparent with the COVID-19 pandemic, shedding a stark light nationally and internationally on the lack of preparedness to protect population health (Sekalala et al, 2020), emphasising the necessity of working with communities.

Keith's article anticipated subsequent political efforts to contain health expenditure, drive systems efficiency, and promote a fairer and just system of improving health outcomes. Yet health inequities have persisted. The first major review of the health and disability sector (Health and Disability Systems Review, 2020) in over 20 years has resulted in a white paper signalling major reforms to “ensure every New Zealander can access the right care at the right time” (Health & Disability Review Transition Unit, 2021, p. 1). Like Keith, the Review identified that service users and communities need to be enabled and empowered to engage in a real partnership in their health, including in commissioning health services for their localities.

Currently, the “overly complex and fragmented [system]” (Health & Disability Review Transition Unit, 2021, p. 1) with 20 district health boards (DHBs) and 30 primary health organisations (PHOs) results in a “postcode lottery” (p. 5) of healthcare. Instead, the reforms will replace the DHBs with a single organisation, Health NZ, to plan and commission services for the whole population, in partnership with a Māori Health Authority, and with a central Public Health Agency. General practice services will no longer be funded through a PHO, allowing locality networks of communities and health workers to plan and commission services in partnership with local iwi and Māori. The intention is to refocus population health as foundational for community wellbeing, shifting the balance away from the treatment of illness towards promotive and preventive services. We can perhaps be cautiously optimistic that the new infrastructure enables dialogue that hears the voices of diverse communities and is facilitated to make decisions to improve equitable access and health outcomes for all in Aotearoa.

Citation: Adams, S., Cook, C., & Jones, S. (2021). Jocelyn Keith's prescient question about the human right to health and healthcare. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 37(1), 14-18. https://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2021.003

I remember, as a young nurse, reading, thinking about and integrating the contents of Jocelyn Keith’s 1987 article “The right to health or the right to healthcare” into an undergraduate nursing assignment. Thirty-four years later I am honoured to be invited to revisit the article, and somewhat amazed at the currency of much of the content. Successive governments have progressed and refocussed Aotearoa’s health agenda toward primary and public health. However, our obligations to the rights of Indigenous peoples, through Te Tiriti and the cultural safety expectations that contribute to improved health equity for Māori and Pākehā (white European ethnicity) have not enjoyed the same attention. In terms of our treaty obligations, racism continues to promulgate health disparities in Māori with devastating consequences.

In addition to racism, other ‘isms’ such as ageism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia and discrimination toward people with disabilities are prevalent in our society and contribute to health disparities in their respective communities. Frequently, the resulting discriminatory practices are insidious, subtle but highly effective, culminating in far-reaching and negative effects on wellbeing and the continuation of health inequities. Some citizens are subjected to and impacted by the influence of more than one ‘ism’, which doubles or triples the discrimination experienced.

Throughout my career, I have been taught that all nursing activity is underpinned by Te Tiriti and culturally safe practice. Why is it then that we continue to uncritically, and at times naively provide care that does not meet the needs of the people of this great land? The provision of all healthcare must be offered in accordance with our Treaty obligations and underpinned by culturally safe practice. Receiving quality healthcare is a human right that everybody should enjoy.

It is my view that nursing now has the professional maturity and political voice to meet our treaty and cultural safety obligations to address existing ‘isms’. As the largest health professional group, we are powerful, but it is how we use and organise that power that is of the utmost importance. A central starting point is to ensure diverse representation of Māori and others across all aspects of nursing. Diversity is central to good governance and should reflect the ethnic and cultural make up of Aotearoa. Doing so will go toward ensuring decisions made about the health and wellbeing of communities will be made by and be beneficial to those communities.

Citation: Neville, S. (2021). The right to health: Discrimination and our responsibilities. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 37(1), 19-20. https://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2021.004

We see clearly that Aotearoa New Zealand’s health system is built on the evidence-based medicine/practice movement (which Keith (1987) refers to as science), which is assumed to solve the ethical dilemmas health professionals face of where to focus their attention. However, the discourse of science privileges biomedical-pharmaceutical knowledge and has not led to enhanced healthcare in terms of reduced health and socio-economic disparities, including the number of children living in poverty. Evidence – science if you will - has typically been directed to service delivery at a secondary and tertiary level, leaving the advancement of the right to health lagging.

This is the situation we have found ourselves in with the COVID-19 pandemic; that the continued emphasis on funding technological secondary and tertiary healthcare advancement has been at the expense of ensuring a robust public health system focussed on the fundamentals of health. Drawing from Bronowski’s (1973) work, Keith argues that humans prepare selectively for imagined futures. The under-investment in primary health care and in improving the social determinants of health mean that in 2021 the right to healthcare continues to eclipse the right to health. This tunnel vision is captured by Askerud and colleagues (2020):

“The social determinants of health are recognised as contributing to the earlier development of long-term conditions, yet for people on low incomes, access to a user-pays primary health-care system remains problematic. Adequately funded person- and whānau-centred care that is embraced by patients and health professionals requires a cultural and systemic change within NZ’s primary care institutions, and for people with multimorbidity in our society. The question remains as to why New Zealanders in 2020 continue to wait for a consistent nationwide approach to long-term conditions care and universal health-care coverage” (p. 121).

Keith argues for “a coherent process of setting needs and determining priorities” (p. 20). Those of us committed to the priorities of primary health care laid out in the Declarations of Alma Ata (WHO, 1978) and Astana (WHO, 2018), and the Ottawa Charter (WHO, 1986), watch with hope and healthy scepticism to see whether the Health and Disability System Review undertaken by the current Labour government will substantively contribute to the right to health.

Citation: Cook, C. (2021). Widening the lens of evidence-based healthcare. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 37(1), 21-22. https://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2021.005

Jocelyn Keith's observation in 1987 that social, political, and economic conditions impact on the uptake of healthcare interventions feels surprisingly current. Health determinants have been extensively researched and there is an evidence-base as to where inequities fall, so why are there still significant gaps in health outcomes? Have health policies and reforms addressed the core issues in service delivery? In Aotearoa, an historic compromise of intended universal access to healthcare means that primary health care (PHC) is predominantly delivered in privately-owned general practices where co-payments are almost universally required (Gauld et al, 2019). This business model, with a fee-for-service, is just one of those structural factors contributing to inequity of health outcomes.

Implementing the nurse practitioner (NP) role shifted the pendulum in the delivery of care away from the once exclusive privilege of doctors. Nurse practitioners' clinical knowledge base would support diagnosis and prescribing, but the mantra was to provide accessible, integrated, and holistic services to underserved and vulnerable populations (Ministry of Health, 1998). Just over half of the 530 strong NP workforce is in PHC, where increasingly the expectation is that the NP encounter with the patient will be the same format and fee as for a general practitioner. How does this utilisation of NPs address the core issues of improving access to healthcare and the right to health?

It is an amazing time to be a NP in Aotearoa. Pioneers have secured a path and have worked relentlessly to alleviate the many barriers to practice. But I believe it is time to revisit our beliefs about the purpose of the role. We marked 200 years since Florence Nightingale's birth in 2020, but the centenary of Loretta Ford, alive and 100 years old in the same year, should cause us to reflect on Ford’s work to develop the NP role, triggered from her own experience as a community-based public health nurse working in child health (Ford 2015). If the vision of making the right to healthcare a reality is our mantra, then NPs need to explore what models of care realise this, and we need to unite our voices in leadership roles to determine the necessary health policy and service provision.

Citation: Bournival, M-L. (2021). The human right to healthcare and the nurse practitioner role. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 37(1), 23-24. https://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2021.006

[Back to Top] [Contents]

| Kiri Hunter, MN RN, PhD candidate, Auckland University of Technology, Aotearoa New Zealand; Ngāti Kahungunu, Rangitāne, Ngāti Maniapoto |

| Jennifer Roberts, EdD RN, Senior Lecturer, Te Kura Tāpuhi / School of Nursing, Massey University / Te Kunenga Ki Pūrehuroa, Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand |

| Mandie Foster, PhD RN, Lecturer & Research Scholar, School of Nursing & Midwifery, Edith Cowan University, Perth, Australia |

| Shelley Jones, RN BA MPhil, Independent Professional Nurse Advisor, Aotearoa New Zealand |

| Commentaries | |

| Denise Wilson | Naku rourou, nau rourou, ka ora ai te iwi |

| Hemaima Hughes | Te hikoi o Kawa Whakaruruhau inanahi ki aianei: The journey to cultural safety yesterday to today |

| Jennifer Roberts | Challenging the status quo: Raising cultural safety, again |

| Fran Richardson | Moving on: From debate to deeper conversations |

Article

Ramsden, I. (1990a). Moving on: A graduation address. Nursing Praxis in New Zealand, 5(3), 34-36. https://doi.org/10.36951/NgPxNZ.1990.009

![]() Ramsden 1990a (1.45MB)

Ramsden 1990a (1.45MB)

Synposis

Dr Irihapeti Ramsden, Ngāi Tahu/Rangitane (1946-2003) was a Māori nurse, educationalist, philosopher, and writer, who leaves an enduring legacy for the development of Kawa Whakaruruhau (cultural safety) both in Aotearoa New Zealand and globally. "The way in which people measure and define their humanity" (Ramsden, 1990a, p. 35) - is the central tenet of this article. “Moving on” was a speech given by Dr Irihapeti Ramsden to Diploma of Nursing graduands at Nelson Polytechnic on 17th November 1989. Ramsden brought together an appreciation of Florence Nightingale's achievements and legacy and our ongoing obligation to provide health services that are respectful and responsive to the humanity of the people needing those services. Of Nightingale, she said, "[i]t would seem appropriate to remember the woman who set up the British model of nursing which still underpins nursing in this country to some extent. We owe respect to Florence Nightingale" (p. 34).

The paper offered a revision of Nightingale’s historical ‘noblesse oblige’ nursing ideology, where privileged people provided care to ‘others’ irrespective of nationality, culture, creed, colour, age, sex, political, religious belief or social status. To facilitate a reduction in health inequities and improve health outcomes for Māori, Ramsden recommended that the unique world views of Māori as tangata whenua (people of the land) and the new settlers, tauiwi (non-Māori), be established and recognised. She reiterated that “the reintegration of body, soul and the environment as envisaged in the Ottawa Charter are part of the Māori reality” (p. 35).

Most importantly was that Māori health (hauora Māori) - the most precious taonga (treasured possession) of all - be maintained with due autonomy and authority. The delivery of appropriate, expert, and equitable healthcare services underpinned by respect, negotiation, partnership, and informed consensual decision-making would then align with the guarantee of tino rangātiratanga (self-determination) made within Aotearoa New Zealand’s founding document, Te Tiriti o Waitangi. The intent of Te Tiriti was to help establish an environment in Aotearoa whereby both tangata whenua and tauiwi could live respective of human difference, acknowledging their different realities. Within the speech antiquated notions of power and relationships in nursing were reframed and contemporised with a simple but powerful interchange of words. Essentially, Ramsden pivots on the word "irrespective" simply shifting it to "respective."

Standout paragraph (Ramsden, 1990a, p. 35):

Context

Ramsden's legacy of Kawa Whakaruruhau (or cultural safety) is a unique taonga in nursing in Aotearoa. Her two articles on Kawa Whakaruruhau - Cultural safety in nursing education Aotearoa (NZ) (Ramsden, 1993) and Cultural safety: Kawa Whakaruruhau ten years on: A personal overview (Ramsden, 2000) - have the greatest citations of any published in Nursing Praxis. The number of citations is just one measure of the impact of her leadership and influence in nursing and healthcare. Beyond Aotearoa, Ramsden’s work has shaped nursing and health professions globally, through indigenous scholarship, innovation, and activism (Koptie, 2009).

Despite cultural safety being a required nursing competence in Aotearoa since the early 1990s, it appears to have had little impact on the experiences of, and outcomes for, Māori in healthcare services. Racism within the health sector, and in nursing, is evident (Harris et al, 2018). The Waitangi Tribunal (2019) Health Services and Outcomes Kaupapa Inquiry (WAI 2575) found health services were not meeting their Te Tiriti obligations to actively protect hauora Māori. Further, the Tribunal identified considerable inequities experienced by the Māori nursing workforce. Qualitative research has described the emotional labour undertaken by Māori nurses working in healthcare services that are not culturally safe (Hunter & Cook, 2020). While the rhetoric of Te Tiriti responsiveness, particularly in achieving mana taurite (equity) is evident across Ministry of Health policy, the reality demonstrates this is an aspiration hindered by layers of eurocentric privileging throughout current systems and practices (Health & Disability System Review, 2020; Roberts, 2020). Through the recently released Cabinet White Paper on the Health Reforms (Health & Disability Review Transition Unit, 2021), a Māori Health Authority will be established as a response to the government's requirements to meet its legislative obligations under Te Tiriti. The intent is that this authority will partner with the new organisation Health NZ on health strategy and policy, and fund and commission kaupapa Māori and te ao Māori-grounded services (where Māori knowledge systems and world views are prioritised). At a local level, the inclusion of iwi and Māori in designing health services gives opportunity to ensure Kawa Whakaruruhau is embedded. Nursing, as the largest health workforce, will need to embrace the mahi (work) required to achieve such necessary and transformational change.

Dr Irihapeti Ramsden’s ground-breaking Kawa Whakaruruhau framework remains critically relevant today. The International Year of the Nurse (2020) coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic and has sharply highlighted how structural racism adversely affects health. Indigenous, minority Ethnic, Black, and Asian populations have been most disadvantaged, including within the nursing and health workforce (Razai, 2021). #BlackLivesMatter has propelled such issues onto the global political stage. The profession of nursing is challenged today to dismantle racism and discrimination as well as those ideologies that maintain them (Moorley et al, 2020).

Citation: Hunter, K., Roberts, J., Foster, M., & Jones, S. (2021). Dr Irihapeti Ramsden's powerful petition for cultural safety: Kawa Whakaruruhau. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 37(1), 25-28. https://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2021.007

I begin where Dr Irihapeti Ramsden ended her 1990 graduation address, "Moving On" (p. 36):

| Naku rourou, nau rourou, ka ora ai te iwi. |

| With your food basket and my food basket, the people will be well. |

This whakataukī signifies the importance of nurses working with Māori to improve equity and wellness while drawing on the attributes, knowledge, and skills nurses bring to their practice with whānau Māori. Working together productively to improve whānau wellbeing is reliant on forming respectful and meaningful relationships and undertaking relevant approaches that are respective of their possibly “uncomfortable realities”. Nurses can play a fundamental role in ensuring equitable access to quality health services that we know many Māori struggle to achieve.

I would argue the historical and futuristic changes Ramsden alluded to have not been sufficiently radical to evoke change. Despite Florence Nightingale advising nurses to work in partnership, Māori and whānau continue to articulate that many nurses ignore how they “define their humanity” and their “uncomfortable realities”. Nurses, the largest health workforce in Aotearoa, need to move beyond the rhetoric of working in partnership and critically reflect on the ways in which they can establish better meaningful relationships with whānau Māori – a fundamental cultural imperative.

Kawa Whakaruruhau, borne out of Māori concerns about their interactions with health services, is Ramsden’s legacy. While Kawa Whakaruruhau underwent a political broadening in its scope to become cultural safety this enabled avoidance and a degree of apathy in embracing it as a fundamental nursing concept. Rather than progressing and evolving cultural safety, nursing has languished in unfulfilled rhetoric and is complicit in the long-standing Māori health inequities, upholding systemic practices deemed to be racist in the WAI 2575 (Waitangi Tribunal, 2019) and Health and Disability System Review (2020) reports. The challenge going forward is for nurses in relatively privileged positions to address nurses’ roles in the causal roots of access and quality issues whānau Māori and others marginalised by the health system in Aotearoa confront.

Citation: Wilson, D. (2021). Naku rourou, nau rourou, ka ora ai te iwi. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 37(1), 29-30. https://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2021.008

How far have we all journeyed as nurses since Dr Irihapeti Ramsden, then Education Officer, Māori Health and Nursing, Ministry of Education, delivered her October 26, 1989 address entitled “He aha te mea nui o te Ao?” (What is the most important thing in the world?)(Ramsden, 1989). Expounding on the importance of wairua and mana within her kōrero, Irihapeti further challenged nursing in her historic report to the Ministry of Education, Kawa Whakaruruhau: Cultural safety in nursing education in Aotearoa (Ramsden, 1990b). In the graduation speech, “Moving on”, she stated, “The time has arrived to review the philosophy which underlines nursing service here.” (Ramsden, 1990a, p. 35).

My first meeting with Irihapeti in 1990 was as an attendee during a national hui for Māori Health employees at Tapu o Te Ranga Marae, Island Bay, Wellington. Her address included Te Tiriti o Waitangi, negotiated partnership, and Kawa Whakaruruhau, stressing the importance of including the cultural mores in the delivery of health care for tangata whenua tūroro (patients). We were inspired, enlightened, empowered and motivated to share this newly found knowledge on return to our various workplaces. My next encounter with Irihapeti was as a newly appointed nurse educator at Nelson Polytechnic. Nelson Polytechnic’s then enthusiastic and supportive head of nursing, Debbie Penlington, eager to set up a Komiti (Committee) Kawa Whakaruruhau, had invited Irihapeti to hui (meet) with a rōpū (group) of Māori registered nurses, iwi (tribal) representatives and others in 1992. The outcome of the rōpū hui was the establishment of Komiti Kawa Whakaruruhau and its composition was in accordance with the recommendations set out on page 8 of the 1990 report (Ramsden, 1990b). Komiti Kawa Whakaruruhau, now at Nelson Marlborough Institute of Technology, is entering its 29th year of existence.

Experientially, as a seasoned Māori nurse educator with a history of 50 plus years in the profession, I do believe that there has been much movement forward by those who have deemed it necessary to become enlightened about the historical and present struggles that continue to impact upon the health of tangata whenua in this land (Walker, 1990). Then there are others who purport to support the concept of Kawa Whakaruruhau and yet still continue to thwart its progression and remain reluctant to relinquish the reins of power and control.

The inclusion and implementation of Kawa Whakaruruhau, Te Tiriti, and hauora Māori within nursing education curricula throughout Aotearoa commenced in 1990 and though inconsistent, its progression continues to this day. In order to be participants engaged in improving the hauora and health outcomes of tangata whenua, as nurses we all need to continue to embrace this whakatauakī (saying or proverb):

| He aha te mea a nui o Te Ao? |

| He tangata, he tangata, he tangata. |

| What is the most important thing in the world? |

| It is people, it is people, it is people |

Citation: Hughes, H. (2021). Te hikoi o Kawa Whakaruruhau inanahi ki aianei: The journey to cultural safety yesterday to today. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 37(1), 31-32. https://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2021.009

Even thirty years following Dr Irihapeti Ramsden’s address, "Moving on", the nursing profession in Aotearoa has significant work to do to realise cultural safety. Recently I undertook doctoral research (Roberts, 2020) exploring experiences and preparedness of nurse educators in working with Māori undergraduate nursing students. I wanted to know if we were in fact, culturally safe in the classroom, and, as a Pākehā, I wanted to learn how the nursing education sector could better serve Māori nursing students and by extension, whānau, hapū, and iwi.

The findings of my research reveal a consistent undercurrent of racism in nursing education and disjointed approaches to cultural safety. Many educators resisted the positioning of Māori as priority learners. Educators had varied understandings and practices of cultural safety and there were significant tensions connected to the historical public backlash to cultural safety in the 1990s. Further, there was a sense that cultural safety was not what Dr Ramsden intended of Kawa Whakaruruhau.

On the other hand, educators’ practices that were enabling for Māori students were aligned with te ao Māori (Māori world view). These were relationship and values driven teaching and learning practices, which authentically connected students and teachers and helped to affirm the need for te ao Māori in what were mostly Eurocentric, white normative spaces in nursing education. What was most unsettling in the findings, however, was the extent that participants described experiencing racism in nursing, either personally, or through student accounts of their experiences.

These findings tell us that there is certainly work to do. Despite cultural safety being an integral part of nursing education, practice, and regulatory landscapes for decades, we are not yet able to provide nursing education or care that, as Dr Ramsden said, is truly respective of those who seek it. Moving into a new decade, with significant attention rightly turned toward equity, racism, and the structural and attitudinal barriers perpetuating white privilege and white normative environments, now it is time for nurses in Aotearoa to again challenge the status quo and raise cultural safety to the top of the professional agenda.

Citation: Roberts, J. (2021). Challenging the status quo: Raising cultural safety, again. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 37(1), 33-34. https://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2021.010

During the 1980s and 1990s Dr Irihapeti Ramsden, a nurse educationalist, challenged those with power in health institutions to examine the impact of their power on health outcomes. Her work on Kawa Whakaruruhau (cultural safety) broke new ground (Ramsden, 1990b). This radical concept became a framework for critically analysing coloniser/colonised (binary) power structures in nursing education and practice. The seemingly small reorienting of words from “irrespective of difference” to “respective of difference” in healthcare (Ramsden, 1990a, p. 35), shifted the focus of care from the provider to the recipient of care.

A critical analysis of power helped identify persistent inequities in healthcare outcomes for Māori. The ideas that inequality of outcomes existed or mattered, that inequality should be addressed or, that nurses could and should address it in their practice, ignited a sustained and heated debate in the popular media. As a Pākehā nursing lecturer I was at the forefront of supporting Irihapeti’s challenge and debate to bring about change in nursing education. With Pākehā colleagues I worked with Pākehā nursing students analysing, identifying, and deconstructing institutional racism (Richardson, 2010). Ramsden and Spoonley (1994) noted, “There was a meeting of the cultural myopia (short-sightedness) of colonialism with the cultural awareness of postcolonial approaches with little common ground between the two” (p. 168). Over the last thirty years has the common ground increased? Yes and no.

Ramsden (1990a) said that for change to happen the “separate reality of Māori needs to be acknowledged and recognised as does the reality of Pākehā” (p. 35). When both realities are acknowledged the relationship moves to a shared understanding through more dialogue and less debate and argument. Two decades into the 21st century, the visibility of Māori working with their reality is increasing. Alas, there is not the same level of tauiwi (non-Māori New Zealanders) working with their reality of power and how this might perpetuate inequity. Having returned recently from eight years teaching in Darwin Australia, I have observed rising levels of tauiwi tension in relation to Māori visibility working with Māori reality. Perhaps this fear might be driven by anxiety about losing power. Blaming and debating right/wrong or doing nothing are not options, transcending the binary is. For tauiwi ‘moving on’ in 2021 is about turning away from the ongoing and ceaseless chatter of racism and ‘moving to’ a place where Tiriti partnerships are negotiated with different language. Language demonstrating relationships of co-operation, understanding, negotiation, respect, and recognition of realities. If equity and transcending the coloniser/colonised relationship is an outcome of cultural safety we have some way to go.

In 2021 health inequities continue, racism continues, there has been little enduring change. To achieve cultural safety in health services tauiwi need to be present, active, and engaged in bringing about equitable healthcare delivery. This means making a commitment to understanding what cultural safety means for them and how it works in practice. Kawa Whakaruruhau began with an analysis of power in healthcare. The need for ongoing analysis is as compelling now as it was thirty years ago. Using language mirroring respect, acknowledgement of power, shared meaning, and equitable negotiation with Te Tiriti partners, will go some way to understanding and creating culturally safe healthcare environments.

Citation: Richardson, F. (2021). Moving on: From debate to deeper conversations. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 37(1), 35-36. https://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2021.011

[Back to Top] [Contents]

| Helen Rook, PhD RN, Senior Lecturer, Te Kura Tapuhi Hauora School of Nursing, Midwifery & Health Practice, Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand |

| Caz Hales, PhD RN, Senior Lecturer, Te Kura Tapuhi Hauora School of Nursing, Midwifery & Health Practice, Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand |

| Kaye Milligan, PhD RN, Senior Lecturer, ARA Institute of Canterbury, Canterbury, Aotearoa New Zealand |

| Shelley Jones, RN BA MPhil, Independent Professional Nurse Advisor, Aotearoa New Zealand |

| Commentaries | |

| Joy Bickley Asher | He Waka Eke Noa: We are all in this together |

| Helen Rook | Rising above polarising discourses within nursing |

| Rhonda McKelvie | Pushing the boundaries: Consciousness and concerted action in times of quantum change |

| Sue Adams | Politics and paradigms in healthcare: Challenging the status quo |

Articles

Wilkinson, J. (2008a). The Ministerial Taskforce on Nursing: A struggle for control. Nursing Praxis in New Zealand, 24(3), 5-16. https://doi.org/10.36951/NgPxNZ.2008.008

Wilkinson, J. (2008b). Constructing consensus: Developing an advanced nursing practice role. Nursing Praxis in New Zealand, 24(3), 17-26. https://doi.org/10.36951/NgPxNZ.2008.009

Synposis

Over two decades ago the Ministerial Taskforce on Nursing (the Taskforce) (Ministry of Health, 1998) made recommendations to the Minister of Health (the Honourable Bill English) to enable nursing to reach its full potential. The Taskforce was established in response to concerns raised by the College of Nurses to “resolve the complex matrix of barriers impeding the full utilisation of nursing services” (Adams, 2003, p. 303) and achieve what the Minister described as, a “much smarter utilisation of nursing skills” (Ministry of Health, 1998, p. 3). The Minister was seeking a more effective contribution from nursing to respond to challenges of the rapidly changing delivery of health care.

Wilkinson (2008a) describes how the Taskforce made recommendations on a range of concerns, including access to funding, education, research, management, and leadership; resourcing the nursing workforce; issues pertaining to Māori; and expanding the scope of nursing by developing new and advanced nursing roles. However, it was this latter concern, including nurse-led services, nurse prescribing, and developing a nurse practitioner (NP) workforce, that became front and centre of the Taskforce’s report. Wilkinson states: “The Taskforce identified substantial attitudinal, structural, legislative and health purchasing barriers to the development of advanced nursing roles. Their recommendations, however, did not arise from a unified nursing voice. Rather, a struggle within nursing arose over the power to control its future” (p. 5).

Through these two articles, Wilkinson describes the conflicted course of the 1998 Taskforce, emerging from her 2007 doctoral thesis The New Zealand nurse practitioner polemic: A discourse analysis. In the thesis, Wilkinson (2007) traced the development of the NP role in Aotearoa describing the divergent discourses both inside and outside nursing as the profession carved a new chapter in its history. In the first article (Wilkinson, 2008a), she describes the constitution and work of the Taskforce and the fractured relationships of the Taskforce membership as they navigated their competing priorities of autonomy and unionism. The Minister appointed a nine-member team “selected for their particular skills and attributes but a ‘fair’ and united representation was an overriding goal” (Wilkinson, 2008a, p.8). However, tensions arose early for two key players, the College of Nurses Aotearoa (New Zealand), and the New Zealand Nurses Organisation (NZNO); the former being more concerned with the professional status of nursing in New Zealand, and the need for additional clinical preparation and masters education – the discourse Wilkinson describes as autonomy; while the NZNO, a union representing the majority of nurses, argued that experience was central to NP qualification and protecting individual members employment rights and conditions - unionism.

Standout paragraph (Wilkinson 2008a, p. 6)

A further dimension Wilkinson (2008a) described related to Māori: “The hasty assemblage of Taskforce membership also jeopardised effective consultation with Māori” (p. 9). While the Taskforce considered themselves bound by Te Tiriti, in actuality, they continued to privilege a non-Māori frame of reference, meaning Māori tikanga (protocol) was neglected and the “pervasive disregard for cultural practices intrinsic to the health sector was paradoxically reproduced” (p. 10).

In the second article, Wilkinson (2008b) describes the tensions within nursing, representing the contrary discourses of autonomy and unionism. There was concern from NZNO (embedded in a unionist discourse) that the NP role required elitist education that would create divisions in the profession. Despite NZNO’s long-standing experience with credentialling the nursing workforce, consensus on the educational requirements could not be reached, leading to the withdrawal of NZNO from the Taskforce. Instead, the Taskforce deferred to the Nursing Council of New Zealand to not only be the regulator with accountability for public safety, but to also stipulate the advanced nursing competencies and monitor master’s level education programmes.

Wilkinson contends that the fractures and divisions that occurred through the period of the Taskforce was problematic for nursing and has had longer-term consequences, including in the role of the Nursing Council of New Zealand. She argues that a more productive course would have seen a ‘unified voice’ and a collaborative effort to advance the practice of nursing and improve healthcare access.

Standout paragraph (Wilkinson 2008b, p. 24-25):

Contemporary context

Wilkinson’s articles remain relevant as they highlight the sometimes difficult realities that precede meaningful advancement. The Taskforce signalled a significant period of Aotearoa’s nursing history, where the role of advanced nursing to meet the ever-changing and expanding healthcare needs of the population was pronounced. Over the past two decades, the development of advanced nursing roles (both registered nurse prescribers and NPs) has required significant changes to legislation and regulation in New Zealand. Since the establishment of the NP role, there are now over 500 registered NPs, with just over half working in primary health. Yet challenges persist to establish NP roles as mainstream healthcare providers (Adams et al, 2020). The Health Workforce Directorate at the Ministry of Health has committed to fund a national Nurse Practitioner Training Programme (NPTP). A national partnership for the NPTP has been specifically designed to provide 500 hours of supervised advanced clinical practice, mentoring by NPs, and to ensure timely NP registration. However, the number of NP trainees far exceeds the national places on offer. Further, Ministry of Health funding has been set aside to establish NP positions to improve access and healthcare for those with primary mental health and addiction needs, particularly in underserved areas and areas with high healthcare need. An important part of this initiative is the development of Māori NP roles and NPs working in partnership with Māori communities. In recognition of the growing NP workforce, Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori Language Commission have given Nurse Practitioners the title Mātanga Tapuhi.

Many articles have been published in Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand about advanced nursing practice ranging from historical accounts (Jacobs, 1998; Jacobs, 2003; Jacobs & Boddy, 2008) and international comparisons of the development of the NP role (Diers & Goodrich, 2008); to questions about the role in relation to nursing's social mandate (Litchfield, 1998; Nelson et al., 2009; Richardson, 2002) and the centrality of caring (Connor, 2003) in nursing; to prescribing rights and practice (Lim et al., 2014); and to political commentary on the challenges and solutions facing NP workforce development (Adams, 2020). The increasing contribution that nursing as a profession, and nurses as individual health professionals make to the promotion and management of the health of New Zealanders is essential.

Citation: Rook, H., Hales, C., Milligan, K., & Jones, S. (2021). Dr Jill Wilkinson's discourse analysis of the sources of power and agency for nursing. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 37(1), 37-41. https://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2021.012

Nothing in nursing occurs in isolation from what's happening in the world at large. Look at the way the current COVID-19 pandemic has turned the spotlight on nurses' work. By comparison, the inside story of Aotearoa New Zealand nursing leaders jostling for control seems lame. Yet, to fully understand the challenges facing the 1998 Ministerial Taskforce, it is necessary to understand the political system in which they were operating.

It was a time when political ideologies romanticised autonomy and freedom and side-lined relational caring, collective action, and Iwi participation. In such a climate, those who are dependent and needy are valued less and therefore, are seen as less deserving of respect and support (Tronto, 2010). This explains the underfunding, for example, of care institutions and any nursing service that is set up specifically to support people in need.

So, what really makes the world tick? Political systems need to accept the reality that caring is a universal resource and need (Tronto, 2010). Caring is everything we do to sustain our world. All human beings are vulnerable, fragile, and are both givers and receivers of care. These ideas resonate with nurses in Aotearoa and with tangata whenua (the Indigenous people of the land) understandings of whakapapa (genealogy), manaakitanga (hospitality), kaitiakitanga (guardianship), and whanaungatanga (connections) (Branelly, Boulton & te Hiini, 2013) (see te reo Māori glossary).

Caring relationships rather than the economy should be the central concern of democratic societies. The purpose of economic life is to support care, not the other way round. In a caring democracy citizens care for others and themselves and for democracy itself (Tronto, 2013). There is evidence of some support of care in both past and present government policies. Nevertheless, now is the time for a radical change in the political system in Aotearoa to promote caring as the fundamental driver of policy change. Who better than nurses to lead the change?

Imagine if relational caring were to lead health policy making. People might be able to measure and define themselves and their need for care. Workplaces (and taskforces) might access caring and democratic systems for dealing with conflict. And nurse practitioners might be able to fulfil their overall purpose of reducing health inequities.

Citation: Bickley Asher, J. (2021). He waka eka noa: We are all in this together. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 37(1), 42-43. https://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2021.013

What has been laid bare by Wilkinson is the grim struggle for power and control within nursing. She describes tension between a discourse of autonomy and a discourse of unionism. The former privileges the individual nurse’s right to autonomous practice, and the latter is a collective approach to secure optimal conditions for all nurses. While we cannot know how these tensions impacted the development of nursing, we do know the nurse practitioner (NP) workforce in particular, has been slow to materialise.

Over the past year the global voice of nursing has strengthened, with the notable activism and leadership of the International Council of Nurses, advocating for both professional autonomy and matters such as safe staffing, pay and conditions. The State of the World's Nursing report (WHO, 2020) and campaigns like Nursing Now provide ample evidence to support the critical role nurses play in tackling global healthcare challenges. The global nursing narrative is one that encapsulates concepts of autonomous practice and working conditions. In Aotearoa however both historically and contemporaneously the collective nursing’s voice is ambiguous and appears at times divided with professional tensions playing out in both social and mainstream media.

Reflecting on both Wilkinson's arguments and global nursing activism, it is clear that discourses of autonomy and unionism need not be dichotomous rivals, and both can offer much to the profession. Fortunately, the creativity and collegiality shown by nurses in Aotearoa during the COVID-19 crisis show that they can transcend polarising discourses. This transcendence leads to professional growth and a hope for the future of nursing.

Hope flourishes in the presence of shared adversity such as a global pandemic. Hope springs from collective vision and shared values. It is both vision and values that guide nurses in knowing what to do in times of crisis. Such professional clarity and direction, muted in a business-as-usual world, are amplified in a COVID-19 world. The polarising discourses described by Wilkinson fade into the background, replaced instead with clarity, collegiality, and purpose. This gives rise to a new more confident nursing voice, enabling the profession to forge ahead and deliver person-centred healthcare: a social mandate to be realised.

Citation: Rook, H. (2021). Rising above polarising discourses within nursing. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 37(1), 44-45. https://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2021.014

Jill Wilkinson's analysis (2008a, 2008b) illuminated how the fundamental tensions in polarised discourses within nursing impacted on the work of the 1998 Taskforce and were consequential for the collaborative effort and pace of progress towards advanced practice roles. Employing a Foucauldian lens (1977), Wilkinson identified how discourses connected to power, underpinned by assumptions and characterised by normative behaviours, construct positioning in relation to the issue at hand.

Quantum changes such as implementing advanced roles and new scopes of practice, initiatives like the Care Capacity Demand Management programme, and graduate entry to nursing programmes, will and always should be subject to critique and challenge from inside and outside the nursing profession. Debate provoked by quantum change reveals a tendency (for some) to rush to the edges of our territory and defend our scope, adopt rigid positions on our boundaries, decry our subordination to medical and managerial hegemony, and pull against the omnipresent tensions of individualism and collectivism. While such tensions and defensive actions can be problematic, they can also be protective of the terrain gained for individuals and the collective of nursing through hard won professional and industrial endeavours.

Debate, robust discussion, argument, and advocacy for a perspective may be experienced as difficult or annoying, but I do not suggest we absolve ourselves of the need for a considered approach to such developments. What I do argue for is that we know what is organising our thinking and our positioning when we enter these boundary negotiating milieus, as was occurring in 1998. A deep interrogation of what is organising our consciousness is the place to start because nurses and the nursing profession navigate a complex terrain of social, gendered, political, institutional, neoliberal, and professional priorities that are powerful and inescapable. Space must be made for differing world views and discursively organised positions, but we must also support each other to get out of our own way. Only then can we make progress at the boundary in the interests of patient care, of nurses, and of nursing. Only then can nurses and the profession push to its full professional potential. Only then, to paraphrase Brene Brown (2017), can we all rise strong.

Citation: McKelvie, R. (2021). Pushing the boundaries: Consciousness and concerted action in times of quantum change. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 37(1), 46-47. https://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2021.015

Rhetoric abounds in every policy and organisational document with the imperative to reduce health inequalities. The drive to establish the NP role was grounded in achieving equity and improving access to healthcare, yet the process was impeded by competing discourses (as Wilkinson identifies) of autonomy and unionism. I would argue that other discourses were at play then and remain the key challenge now.

The healthcare sector remains dominated by the biomedical-pharmaceutical-technical discourse, including general practitioner-led primary care. All too easily, nurses are unconsciously hooked into this paradigm, with little critique or awareness of alternative ways of meaningfully delivering services. Added to this, the persisting neoliberal discourse drives self-responsibility, efficiencies, and managerialism. Yet nursing has a long and strong history of activism, challenging the status quo, and paving the way for far-reaching primary health care (PHC) nursing services, firmly embedded in a social justice paradigm. But not all of nursing embraces this paradigm. Divisions remain across education, practice, and policy. We see this play out in the allocation by DHBs of Health Workforce funding for postgraduate education for NP training. Not only is funding unequally distributed between the acute sector and PHC, but equity (in relation to both the workforce and population) is rarely addressed.

The Health and Disability System Review (2020), together with the findings of WAI 2575, have challenged our existing models of healthcare provision and the unacceptably high levels of both health and workforce disparity. Nurse practitioners work at the intersection of biomedical-pharmaceutical-technical care with a social justice and equity paradigm to improve healthcare access. The release of the new White Paper for health reform of the sector (Health and Disability Transition Unit, 2021) provides opportunity to refocus service design that engages with and meets the needs of local communities with a focus on hauora and equity. We should expect NPs to be central in both design and delivery. But as we enter the planning stage for the implementation of this major restructure, will the paradigms of medicine and private practice ownership remain dominant? Be aware that in the corridors of power the lobbyists are already at work to protect self-interest and the status quo. Nurses must take every opportunity to be at the table of policy-making and with a unified voice that at the very least espouses the contribution of all scopes of nursing practice to health equity.

Citation: Adams, S. (2021). Politics and paradigms: Challenging the status quo. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 37(1), 48-49. https://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2021.016

[Back to Top] [Contents]

Reading these powerful papers in previous issues of Praxis provides a salutary glimpse into the arduous journey that has been nursing in Aotearoa New Zealand in the last 30 years or so. Underlying all of these papers is a recognition that biomedicine alone will not achieve health for all and that nursing has a responsibility to act as an agent of transformation for delivering healthcare with a focus on epidemiology, equity, and well-resourced primary health care which meets the needs of even the most vulnerable. Our journey has been one that has focussed (as we titled the Ministerial Taskforce on Nursing, 1998) on Releasing the potential of nursing. That agenda has recently been taken up the Nursing Now Campaign, affirmed by the World Health Organization and captured in the State of the World's Nursing report (WHO, 2020). The need to release the potential of nursing has never been greater.

We have had had our own internal struggles to contend with, as outlined so clearly in Wilkinson’s articles. Further, the voices in all of these articles have not always been heard nor embraced by all nurses. We still struggle with the antiquated and highly counterproductive notion that nurses who lead, who research, who carry out diverse roles away from direct patient contact have somehow lost touch, lost credibility, and should be silent. This is deeply ironic given that nurses who practice in direct care roles are almost always silent for a variety of reasons both good and bad.

Yet looking back a huge amount has been achieved. There has been significant development of clinical postgraduate education and an internationally enviable development of the nurse practitioner role free from many of the constraints which hamper this scope of practice in other countries. Prescribing at three different levels is well established with a simple goal to improve access to care. There is significant and genuine collaboration across all peak nursing bodies through the auspices of the National Nurse Leaders Group which meets four times yearly to focus on strategic development for nursing. But there is so much more to be done.

As the philosopher Michel Foucault so clearly indicated, power is generated from the bottom up and through the micro activities of our daily actions. We hold the power in our hands to shape the future of nursing. We will achieve that through supporting, strengthening and above all trusting each other; as leaders, as clinicians, and in every role that nursing or nurses hold. We need to strengthen our capacity and engagement in the policy environment, drop forever our tendencies to silence and stay whole heartedly focussed on the reasons we chose nursing, so we make a difference to people’s health and illness experience with skill, knowledge, evidence, passion, and compassion.

Citation: Carryer, J. (2021). The need to release the potential of nursing has never been greater. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 37(1), 50-51. https://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2021.017

[Back to Top] [Contents]

We would like to thank the following people and organisations for their support and contribution to making this Special Issue possible: Shelley Jones, who was contracted to manage the project; College of Nurses Aotearoa for funding the Special Issue; Editorial Board for their ongoing support and contributions to writing and reviewing; and lastly Dr Sue Adams, Editor-in-Chief, for her leadership, vision, and commitment to publishing the Special Issue. Particularly we want to acknowledge and thank the commentators for their generosity in time and knowledge to make this issue possible.

[Back to Top] [Contents]

Adams, K. F. (2003). A postmodern/poststructural exploration of the discursive formation of professional nursing in New Zealand 1840-2000 [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Victoria University of Wellington.

Adams, S. (2020). Myths, cautions, and solutions: Nurse practitioners in primary health care in Aotearoa New Zealand [Editorial]. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 36(1), 5-7. https://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2020.001

Adams, S., Boyd, M., Carryer, J., Bareham, C., & Tenbensel, T. (2020). A survey of the NP workforce in primary healthcare settings in New Zealand. New Zealand Medical Journal, 133(1523), 29-40.

Amnesty International. (2021). COVID-19: Health worker death toll rises to at least 17000 as organizations call for rapid vaccine rollout. Author. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/03/covid19-health-worker-death-toll-rises-to-at-least-17000-as-organizations-call-for-rapid-vaccine-rollout/

Askerud, A., Jaye, C., McKinlay, E., & Doolan-Noble, F. (2020). What is the answer to the challenge of multimorbidity in New Zealand? Journal of Primary Health Care, 12(2), 118–121. https://doi.org/10.1071/HC20028

Bickley, J. (1987). The white nation has a lot to answer for: Towards an analysis of racism. Nursing Praxis in New Zealand, 3(1), 23-28. https://doi.org/10.36951/NgPxNZ.1987.009

Brannelly, T., Boulton, A., & te Hiini, A. (2013). A relationship between the ethics of care and Maori world view-the place of relationality and care in Maori mental health service provision. Ethics & Social Welfare, 7 (4), 410-422. https://doi.org/10.1080/17496535.2013.764001

Bronowski, J. The ascent of man. Little Brown & Co.

Brown, B. (2017). Rising strong.: How the ability to reset transforms the way we live, love, parent, and lead. Random House.

Chalmers, L. (2020). Responding to the State of the World’s Nursing 2020 report in Aotearoa New Zealand: Aligning the nursing workforce to universal health coverage and health equity. Nursing Praxis in Aotearoa New Zealand, 36(2), 7-19. https://doi.org/10.36951/27034542.2020.007

Connor, M. J. (2003). Advancing nursing practice in New Zealand: A place for caring as a moral imperative. Nursing Praxis in New Zealand, 19(3), 13-21. https://doi.org/10.36951/NgPxNZ.2003.010

Diers, D., & Goodrich, A. W. (2008). “Noses and eyes”: Nurse practitioners in New Zealand. Nursing Praxis in New Zealand, 24(1), 4-10. https://doi.org/10.36951/NgPxNZ.2008.002

Ford, L. C. (2015). Reflections on 50 years of change. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 27(6), 294-295. https://doi.org/10.1002/2327-6924.12271

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Pantheon Books.

Gauld, R., Atmore, C., Baxter, J., Crampton, P., & Stokes, T. (2019). The ‘elephants in the room’ for New Zealand’s health system in its 80th anniversary year: General practice charges and ownership models. New Zealand Medical Journal, 132(1489), 8-14.

Harris, R. B., Cormack, D. M., & Stanley, J. (2018). Experience of racism and associations with unmet need and healthcare satisfaction: The 2011/2012 Adult New Zealand Health survey. Australian Journal of Public Health, 4(3), 75–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12835

Health and Disability Review Transition Unit. (2021). Our health and disability system: Building a stronger health and disability system that delivers for all New Zealanders [White Paper]. Wellington: Author. https://dpmc.govt.nz/publications/health-reform-white-paper-summary

Health and Disability System Review. (2020). Health and Disability System Review: Final report Pūrongo Whakamutunga. Wellington: Author. https://systemreview.health.govt.nz/